In my keyboard research, one of the most amazing and constant features is how *early* some of the ideas appeared.

Often, the things that seem to only make sense in the computer universe, existed much earlier, in the physical world.

Marcin Wichary

22 February 2019 / 25 tweets / 58 photos

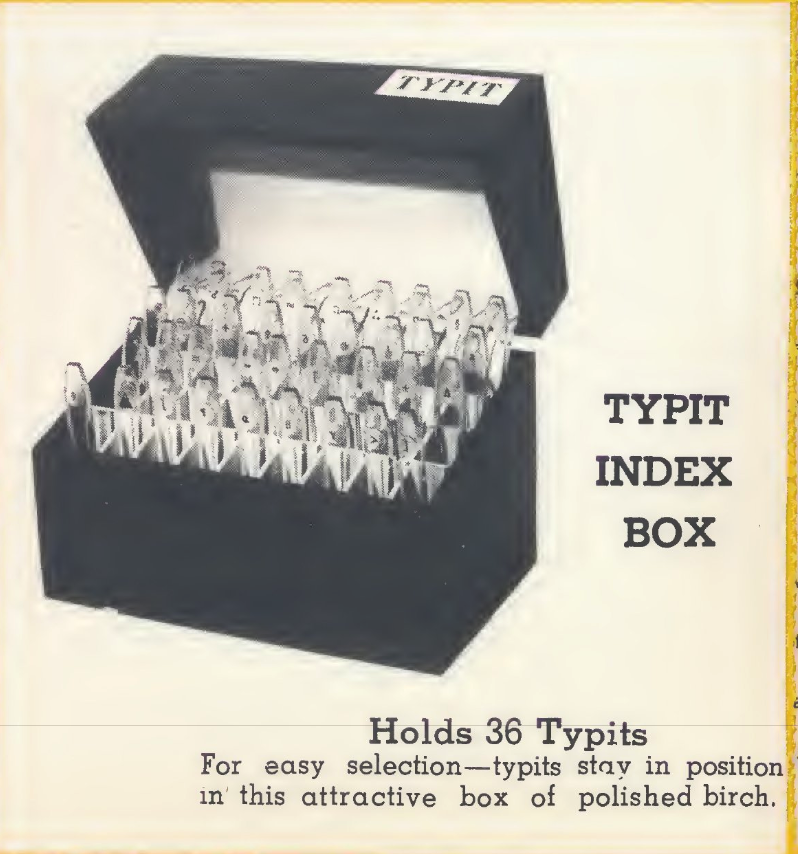

A hack named Typit

This is an archive of a Twitter thread from 2019. I have since deleted my Twitter account.

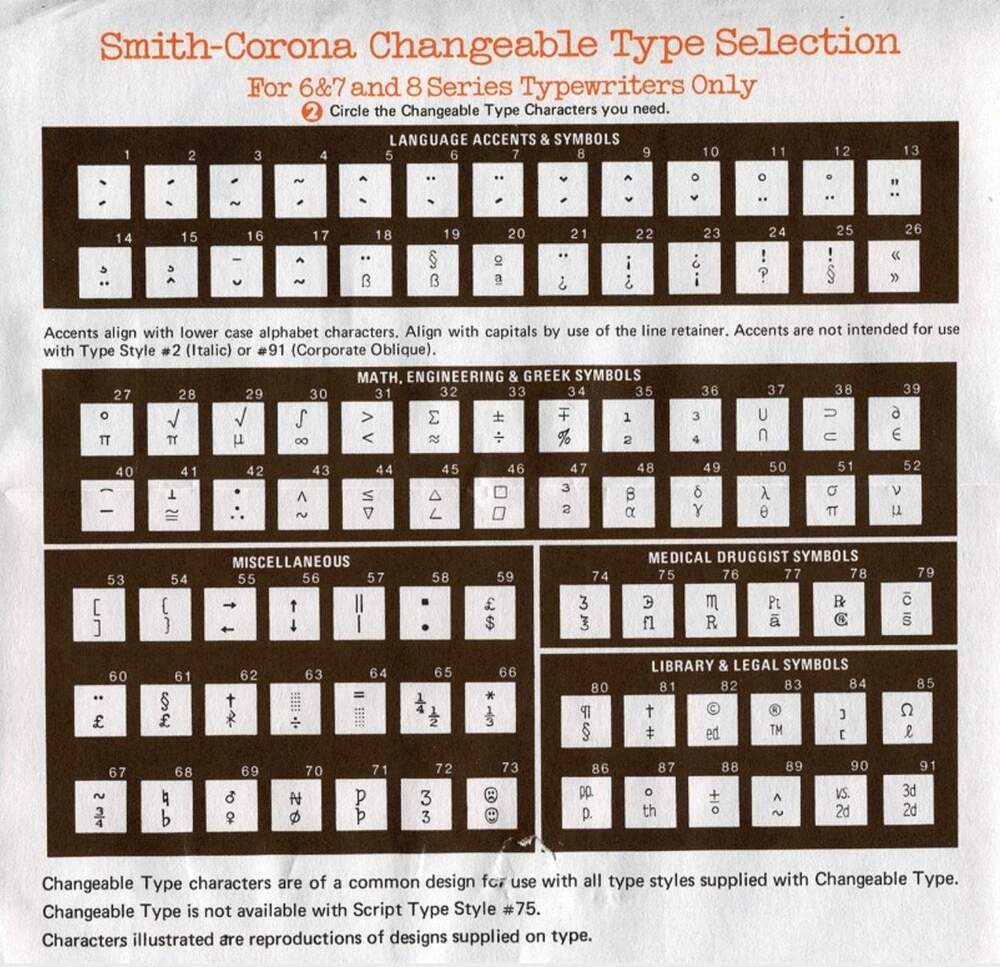

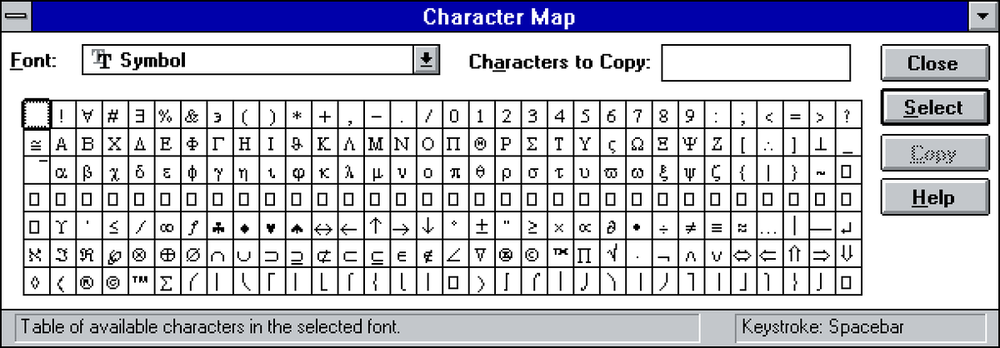

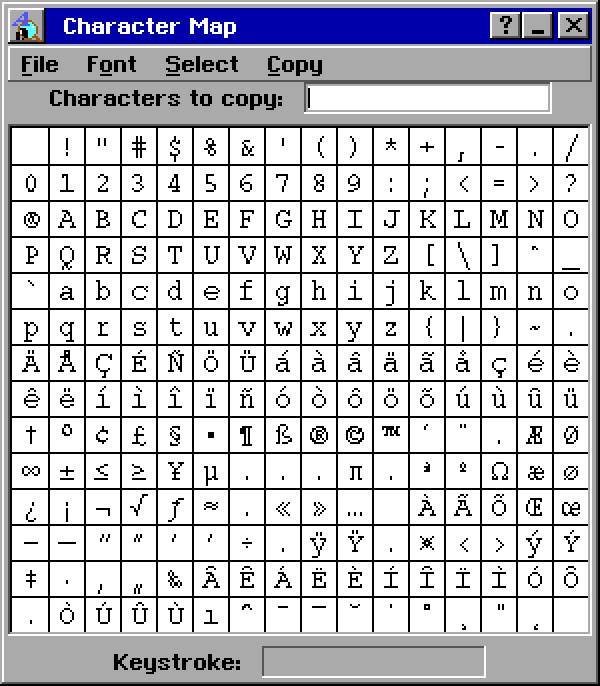

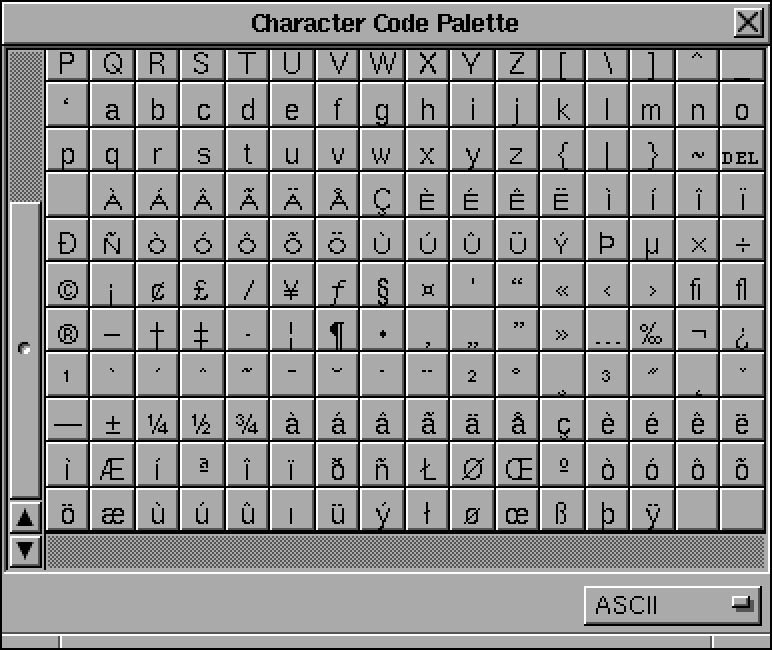

Take this, for example. It’s a panel you might recognize from your Mac, or Android phone, or any other device – a simple way for anyone who’s not a typesetter to access special characters unavailable from the keyboard.

That’s easy for computers that can hide things inside, but what about typewriters?

From their very first year, it has always been an issue of what to do when you needed to print a character that your keyboard didn’t have.

From their very first year, it has always been an issue of what to do when you needed to print a character that your keyboard didn’t have.

Overtyping could only get you so far, and pencilling or penning things in after typing was cumbersome and unprofessional.

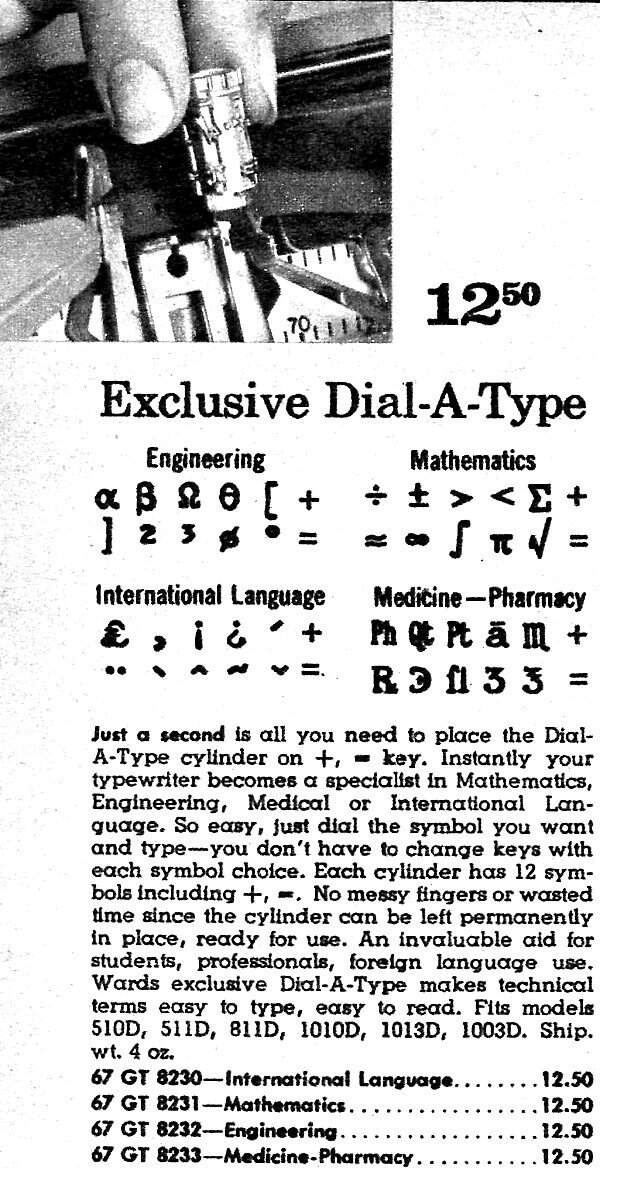

And so, some typewriters started offering changeable or mutil-faceted typebars, but that would only get you a bunch of new characters… not nearly enough.

(Dial-A-Type™ is such a great name, though.)

(Dial-A-Type™ is such a great name, though.)

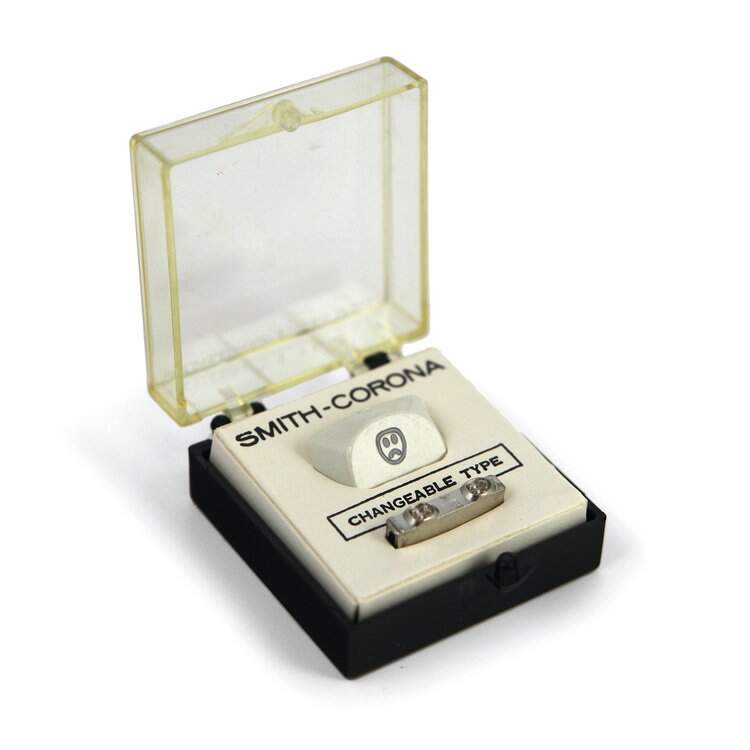

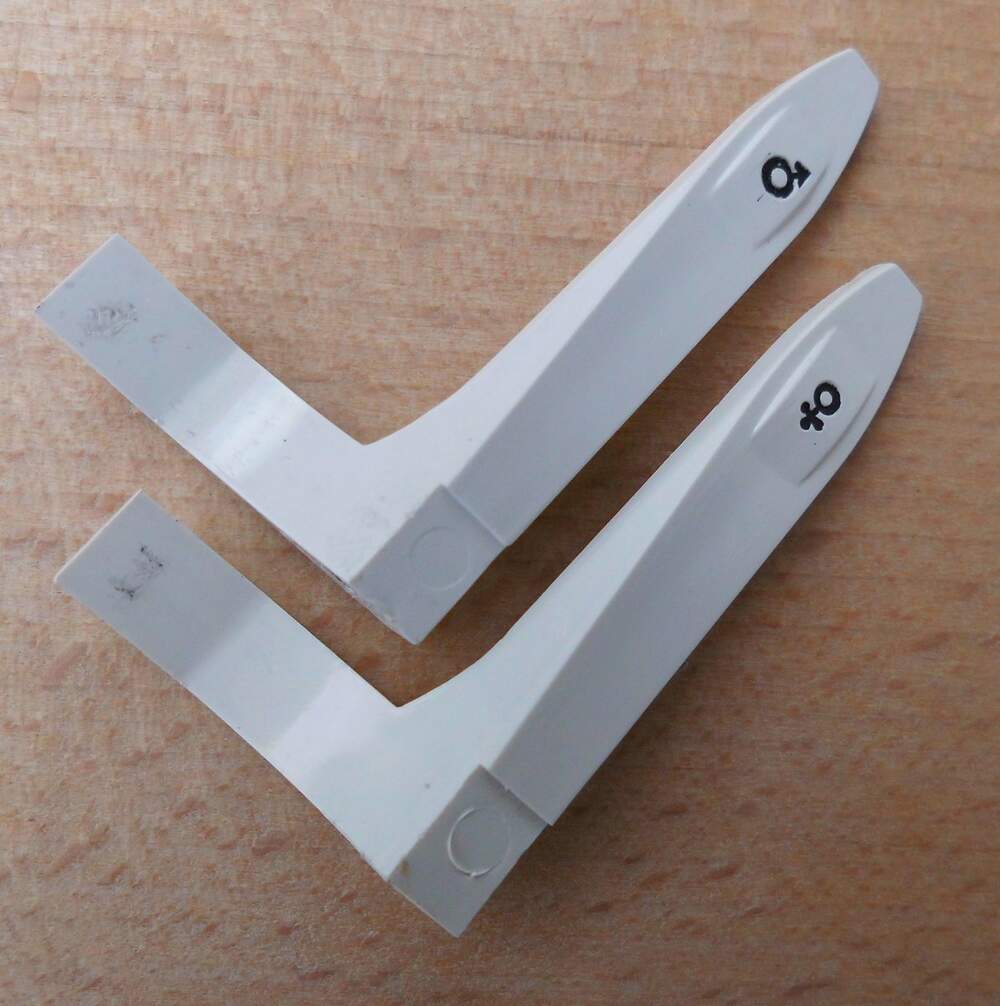

Others allows you to buy a new key and a matching typebar. But usually, only a few designated keys were swappable.

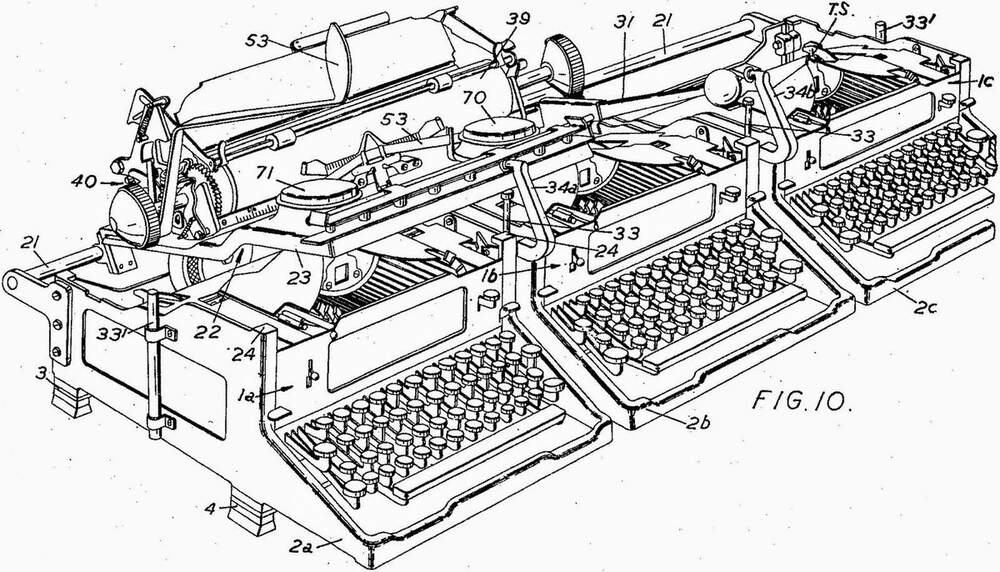

Other typewriters – this is not a joke – offered twin models that effectively joined two typewriters together, but that was ridiculously expensive, and only extended your runway via 40 or so new characters.

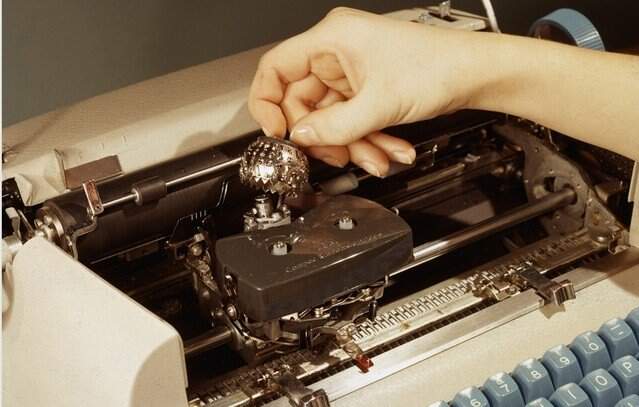

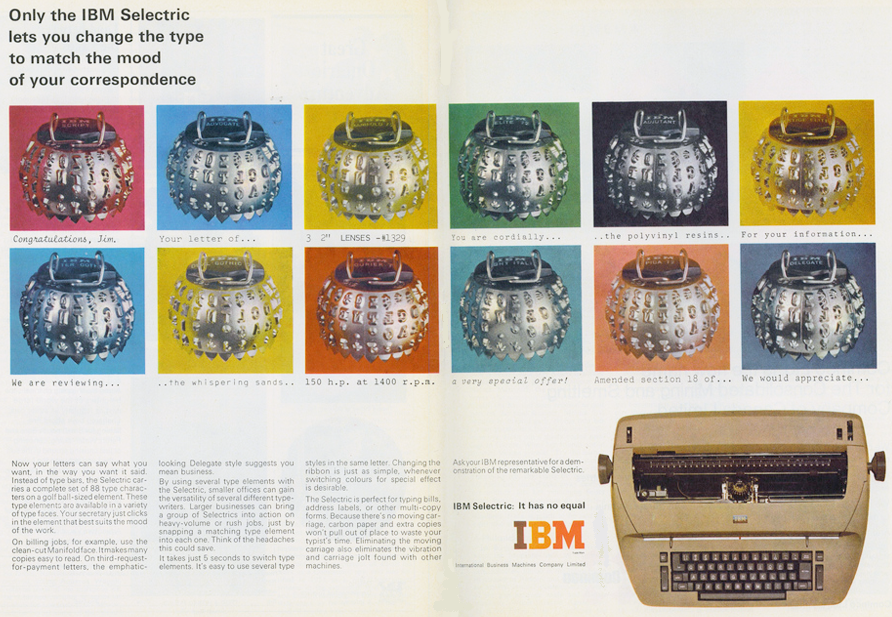

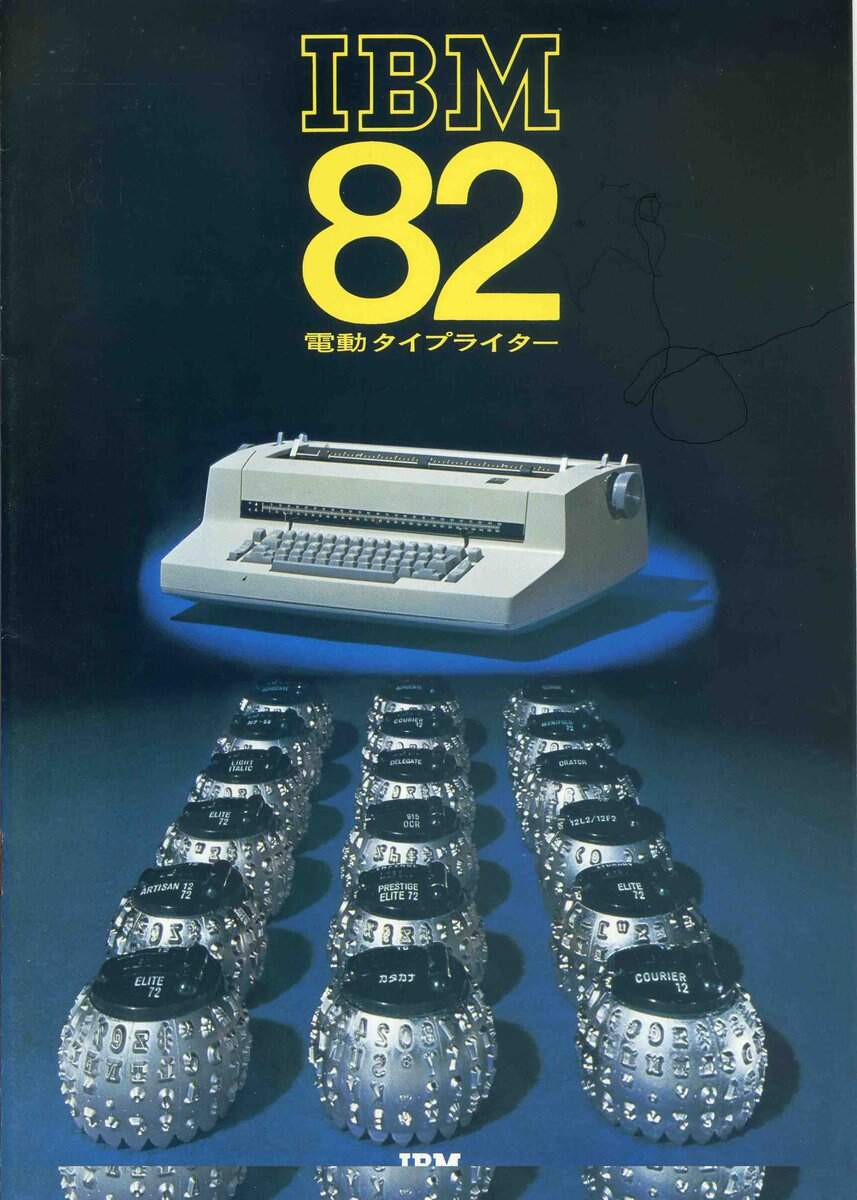

The most popular solution in this space was a Selectric, a typewriter with an interchangeable type ball, introduced by IBM in 1961.

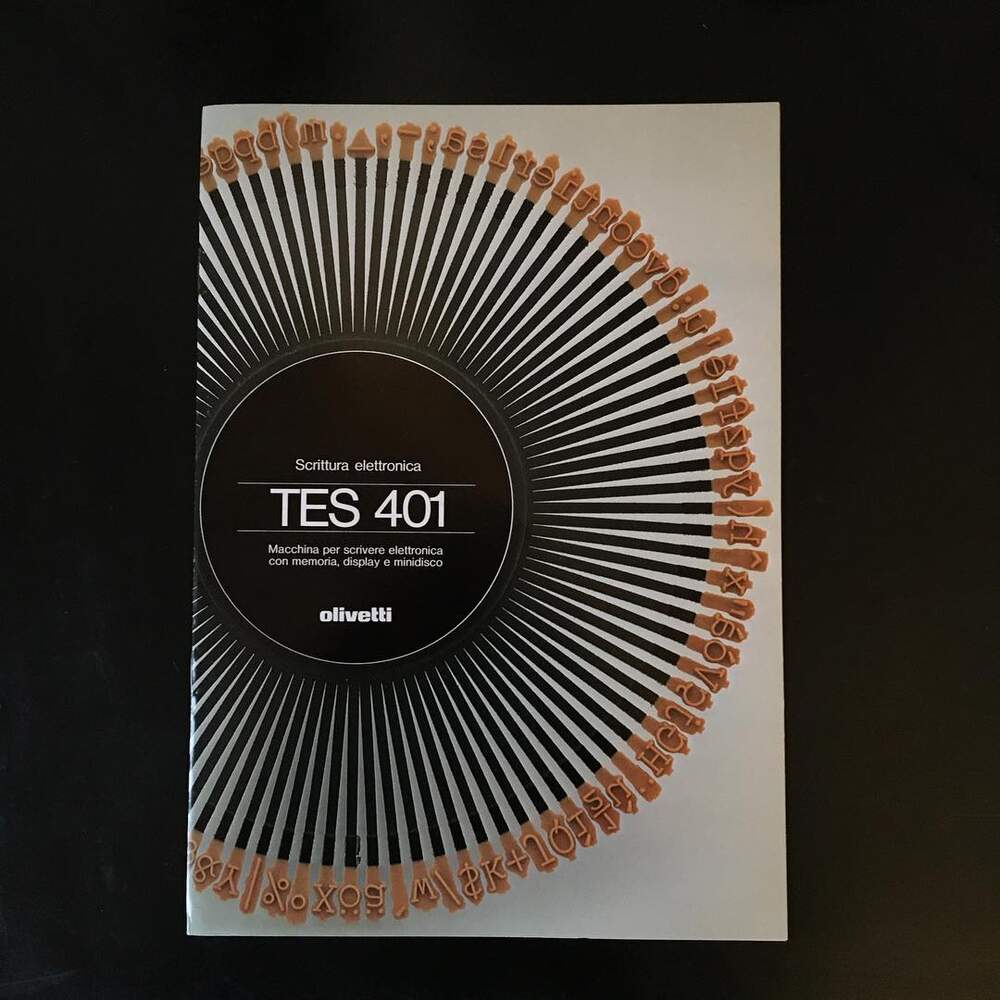

The “golf balls” proved immensely popular, were copied by many other typewriter companies, and in time morphed into daisy wheels.

But while there were many balls with various fonts, there weren’t that very many with symbols.

Besides, that solution was pretty tough – you had to swap the entire ball, and then press exactly the right key (and your key cap wouldn’t match the symbol at all).

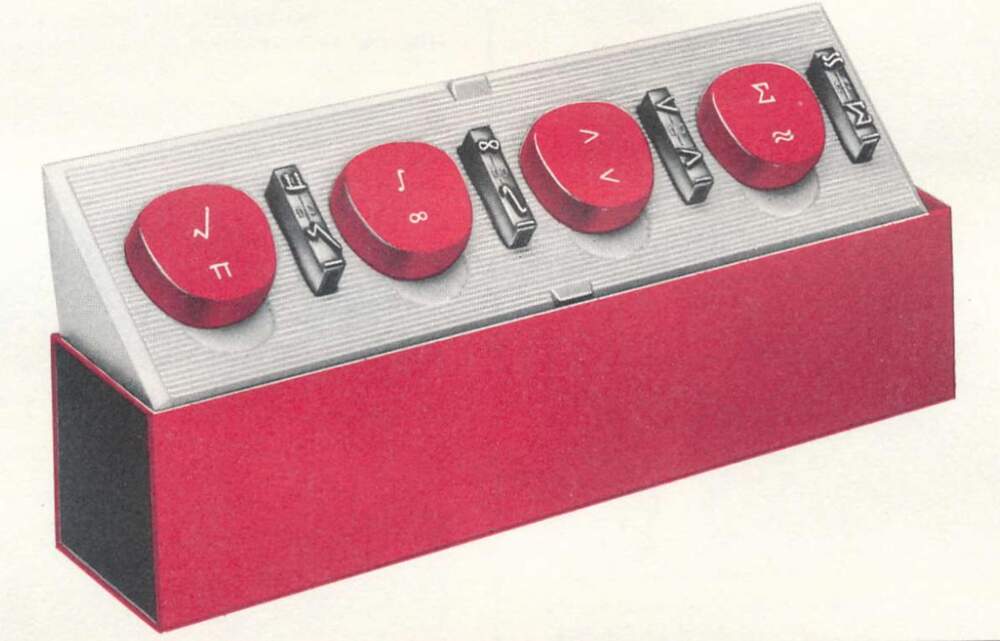

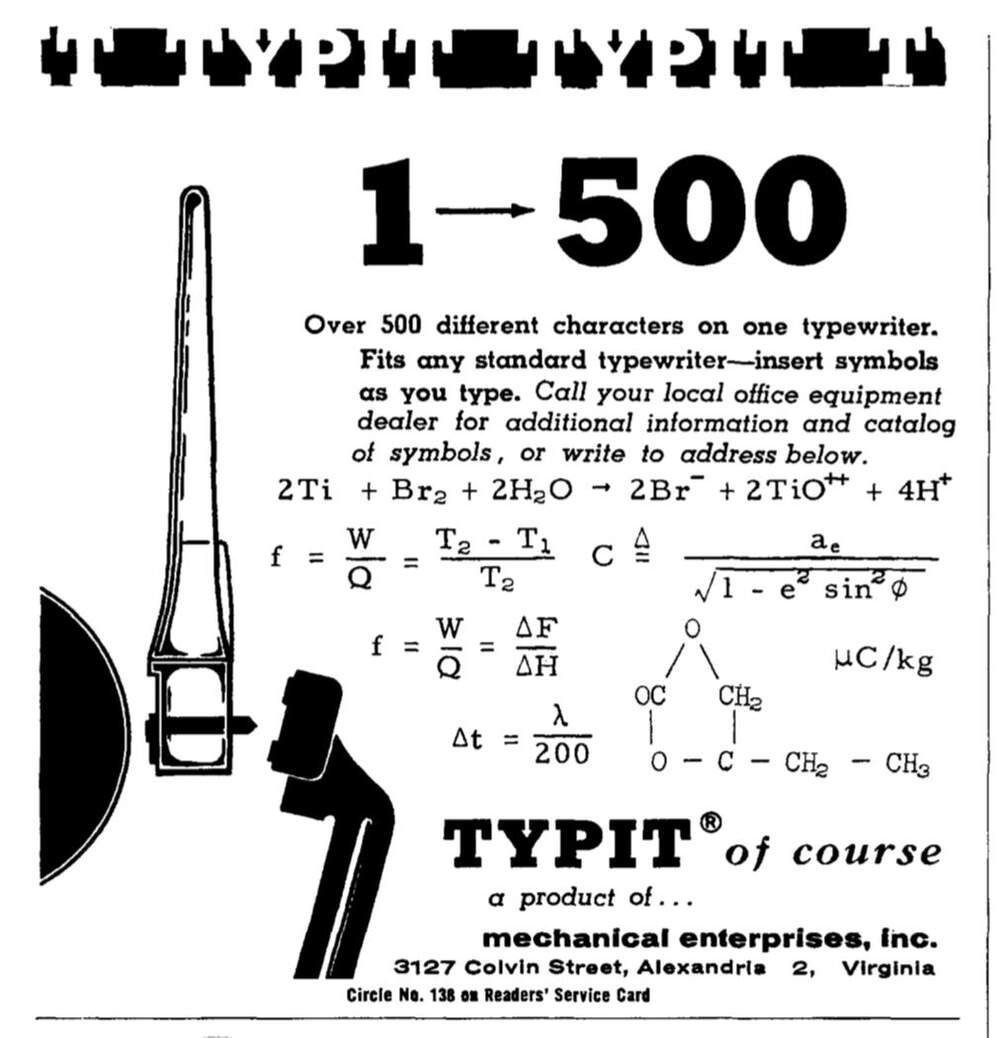

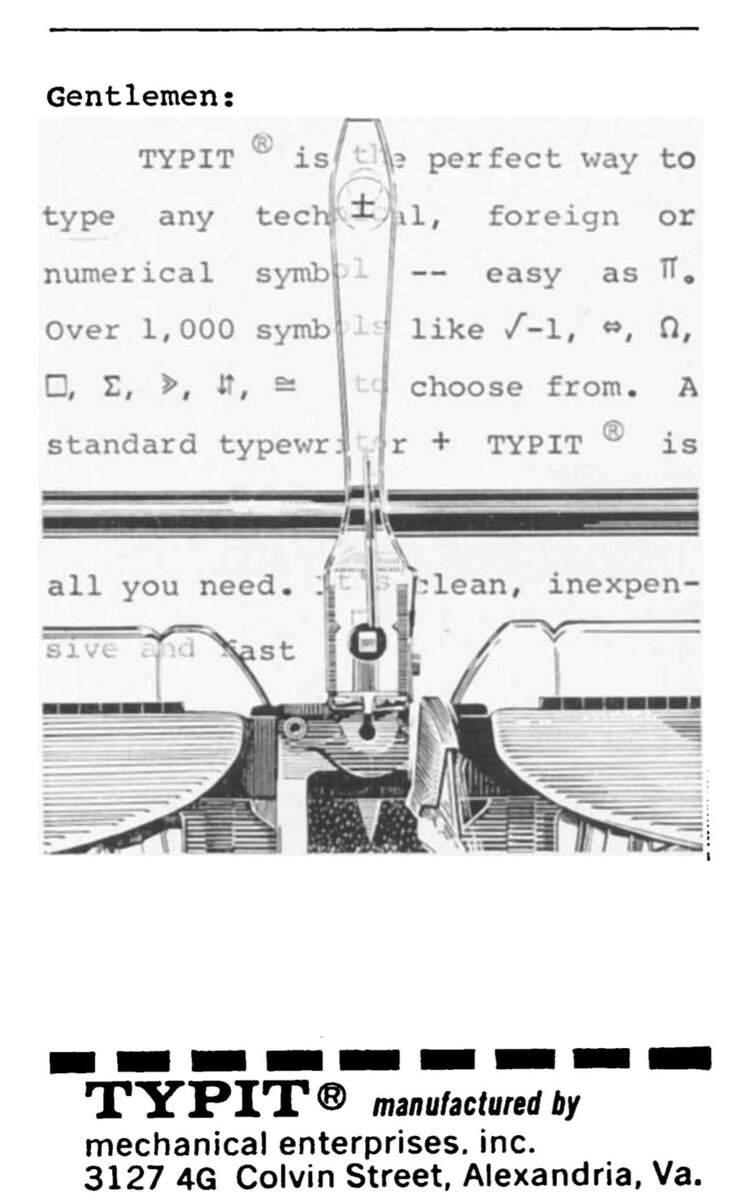

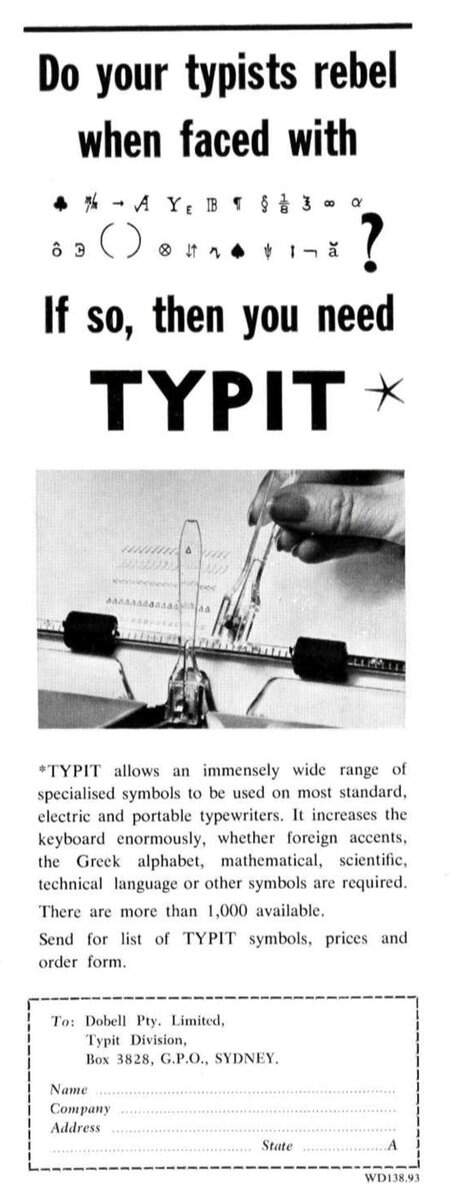

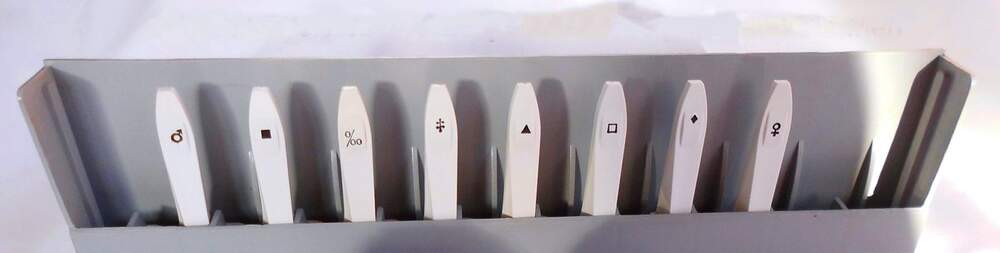

So imagine my delight when I recently discovered an obscure third-party system for typewriters called Typit.

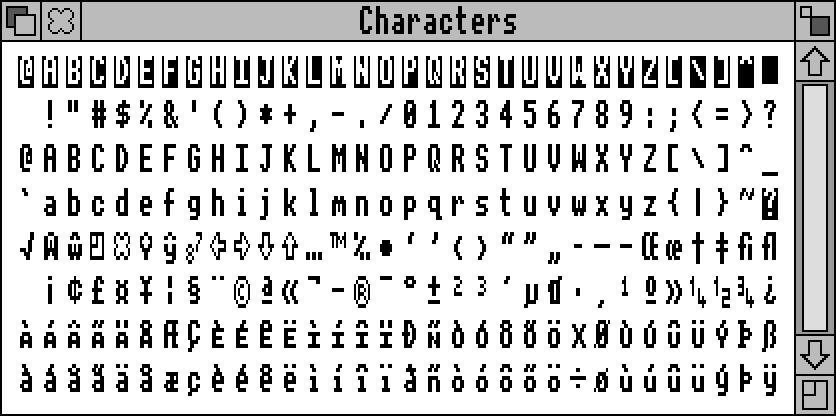

It is very much the same idea as the Mac OS panel we looked at atop, but realized in the world without pixels.

It is very much the same idea as the Mac OS panel we looked at atop, but realized in the world without pixels.

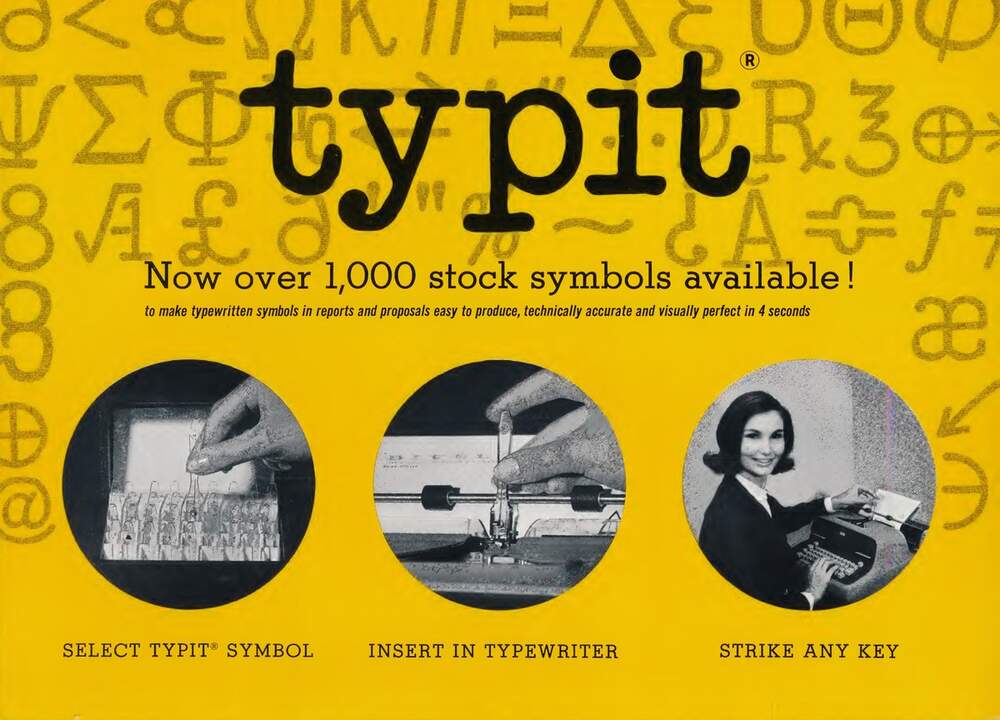

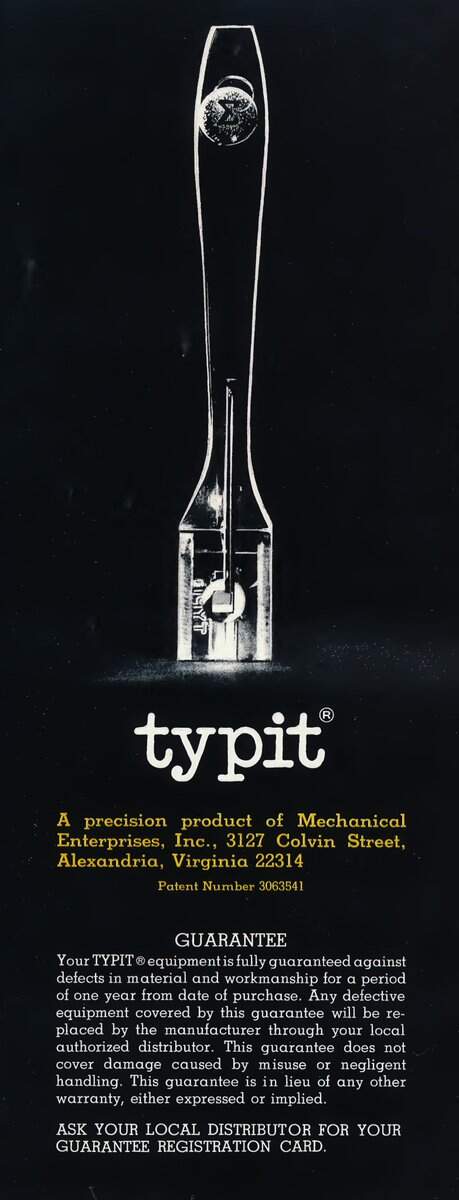

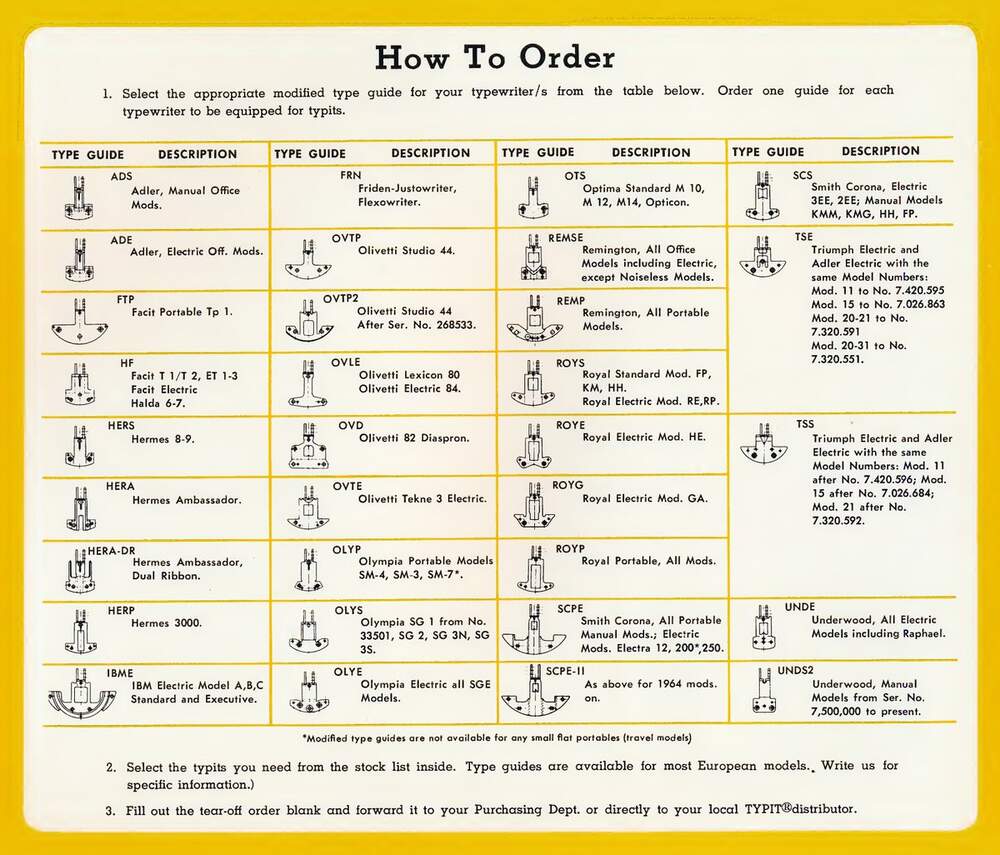

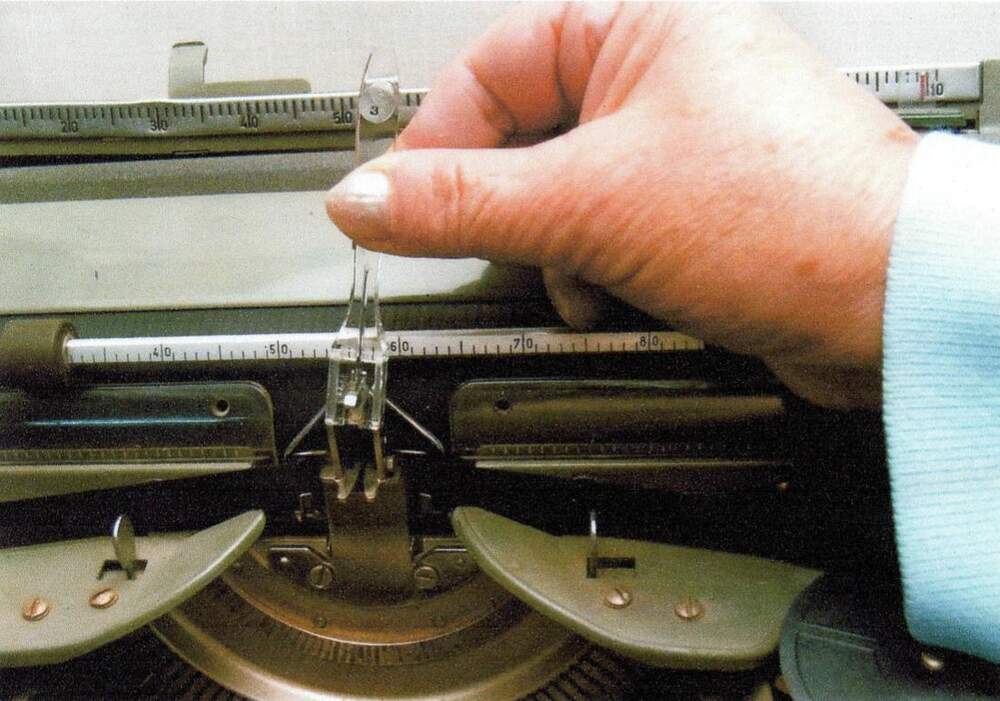

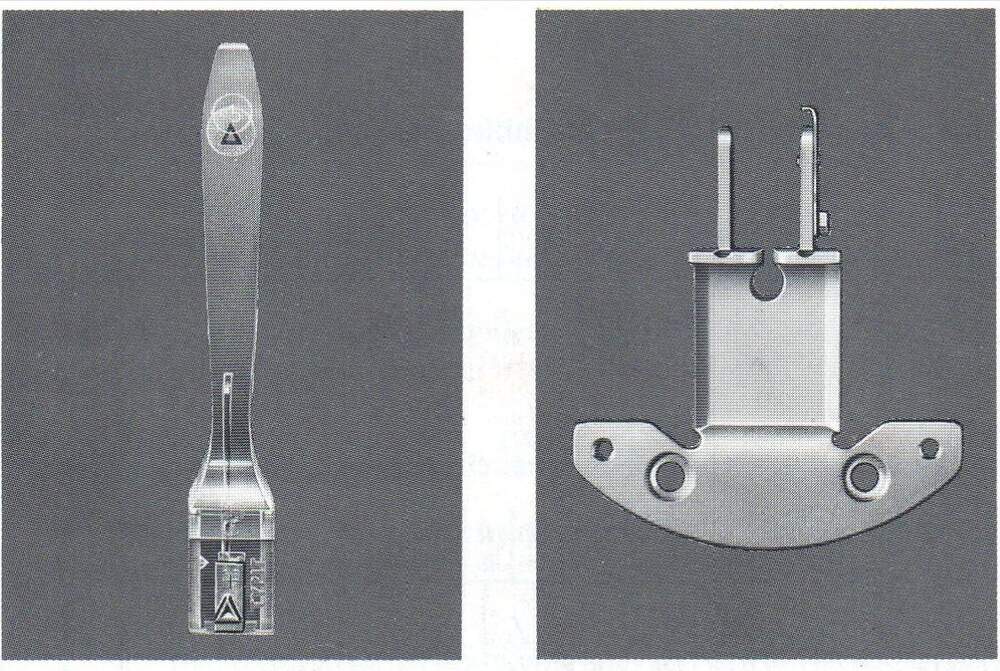

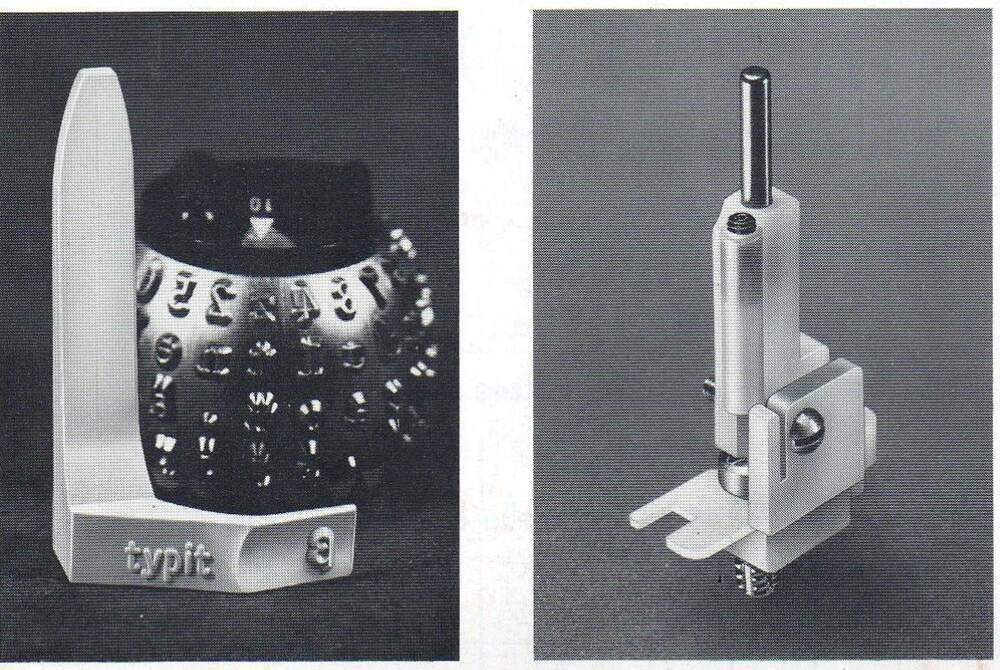

Typit was pretty clever. First, you had to buy a physical add-on for your typewriter – a special adapter that you only had to install once, and that wouldn’t otherwise impede regular typing.

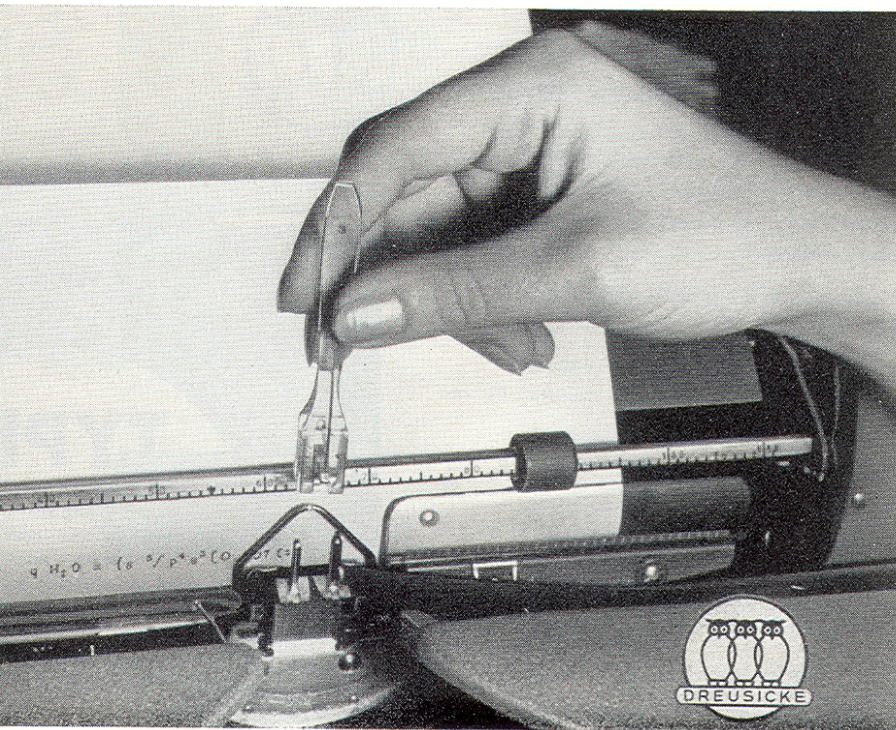

Then, you could purchase any extra characters you needed. And if you wanted to type one, you’d grab it, and mount it quickly in the adapter, in front of the typebar…

And then, you would press a regular typewriter key. The typebar would swing normally, but then hit the just-inserted character, then the ribbon, and then the paper.

In a sense, Typit functioned almost like a parasite.

In a sense, Typit functioned almost like a parasite.

(A rather momentary parasite. Typit creator promised printing any character should take only ~4 seconds, with the quality identical as the typewriter’s “native” text.)

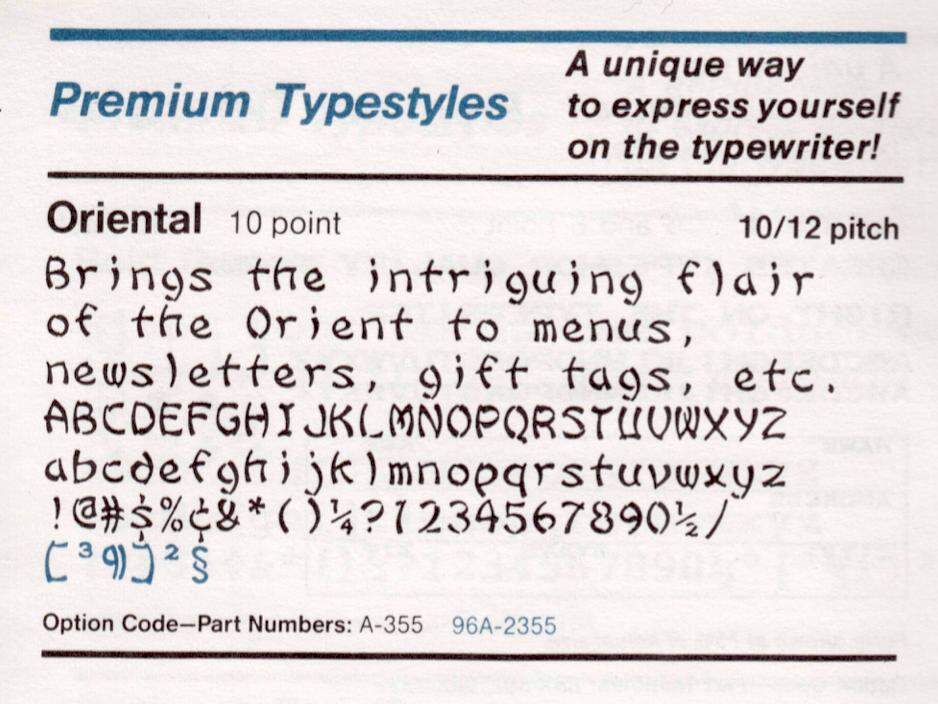

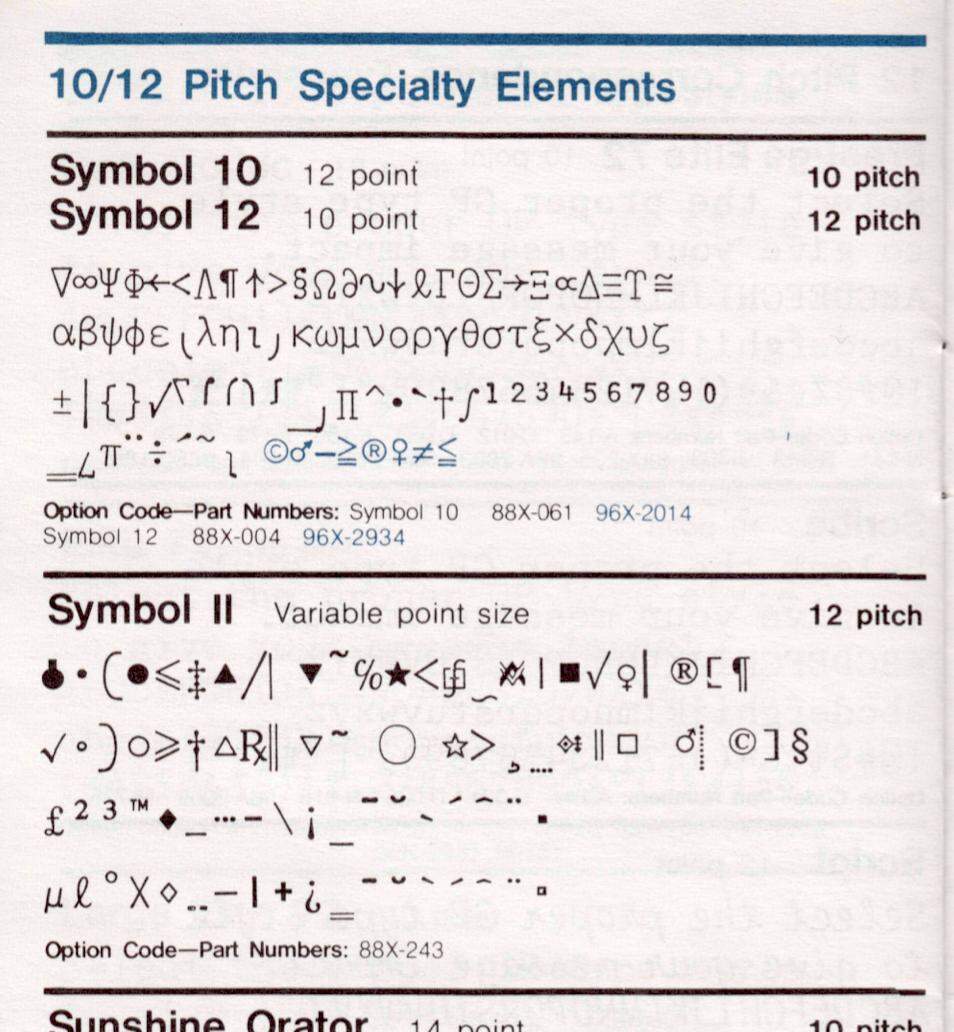

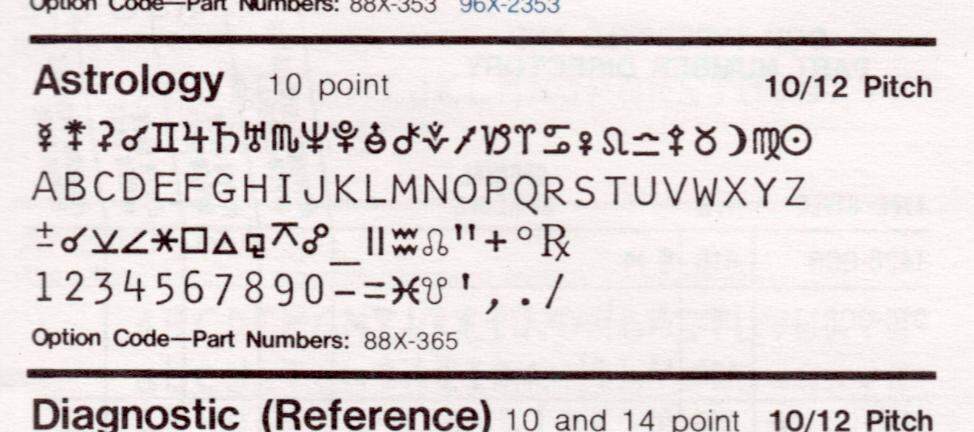

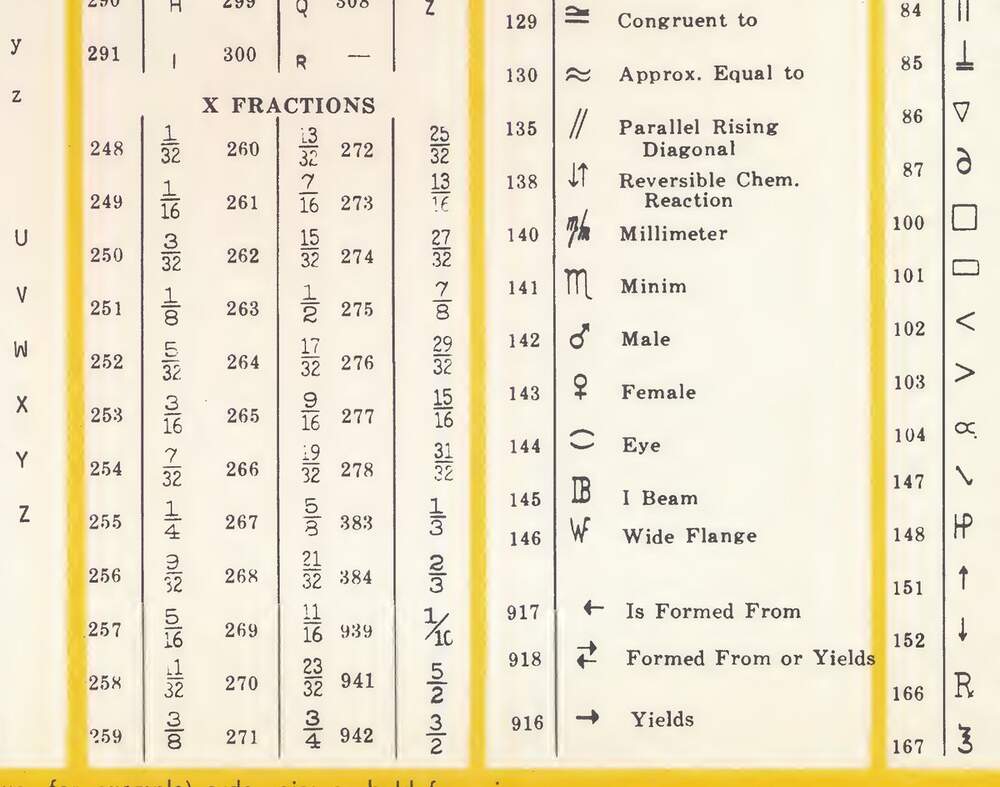

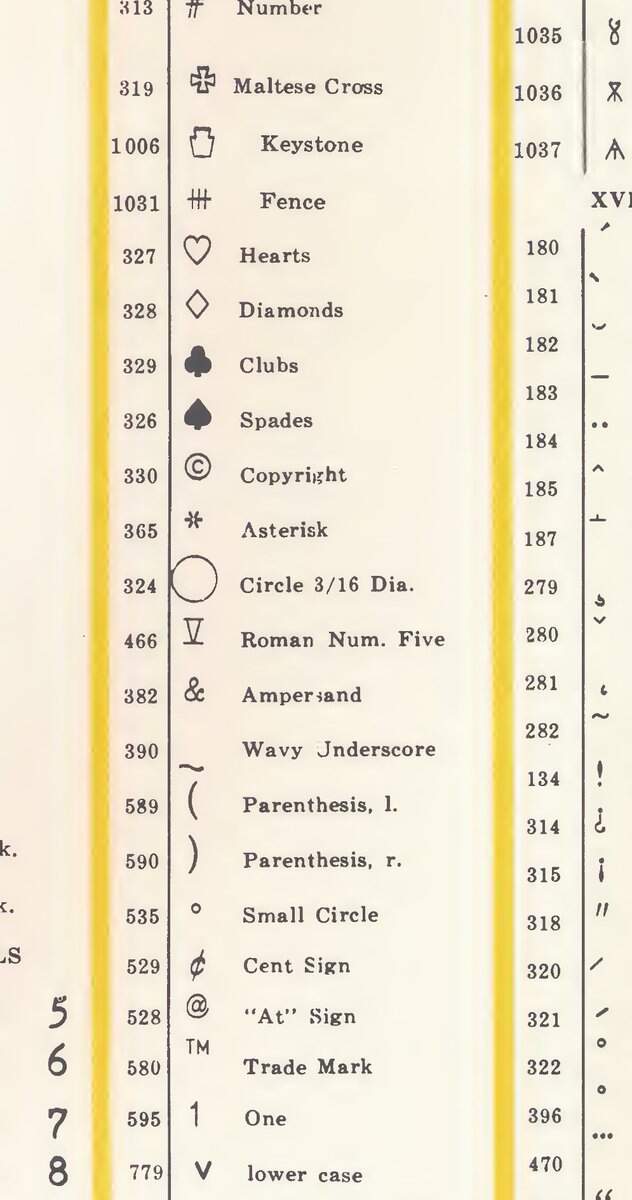

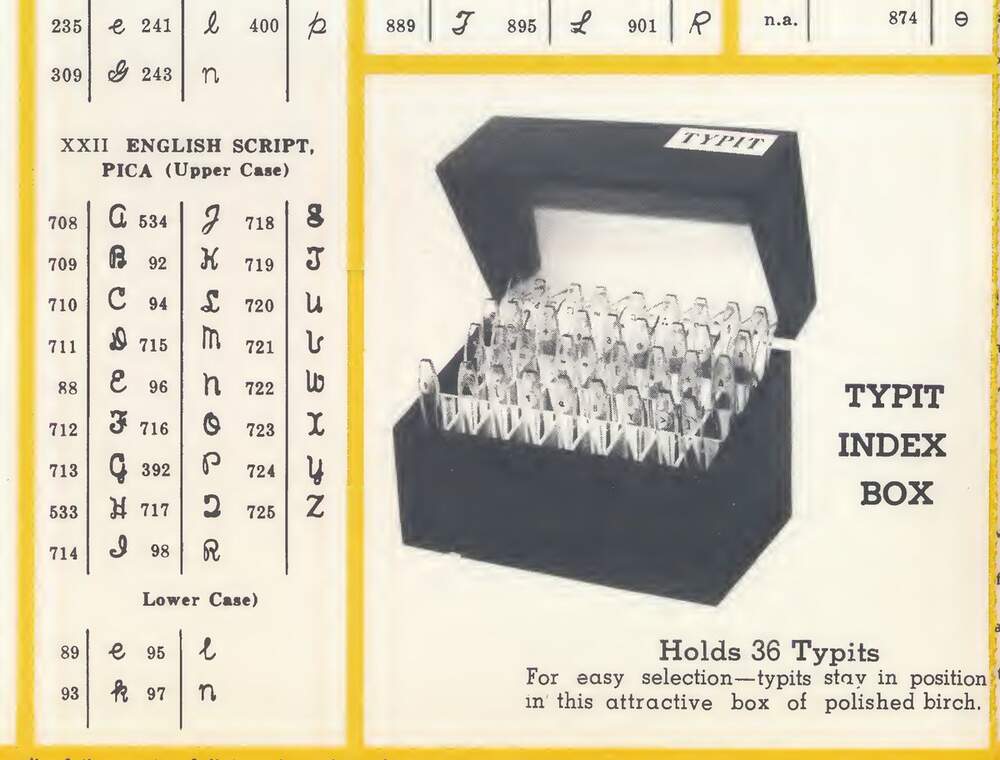

Some 1,500 characters were available, effectively creating the only “typewriter Unicode” I know of – math symbols, different alphabets, fractions, even keys your old typewriter might be missing (e.g. digit 1 or &).

It seems each character would cost you about $10.

It seems each character would cost you about $10.

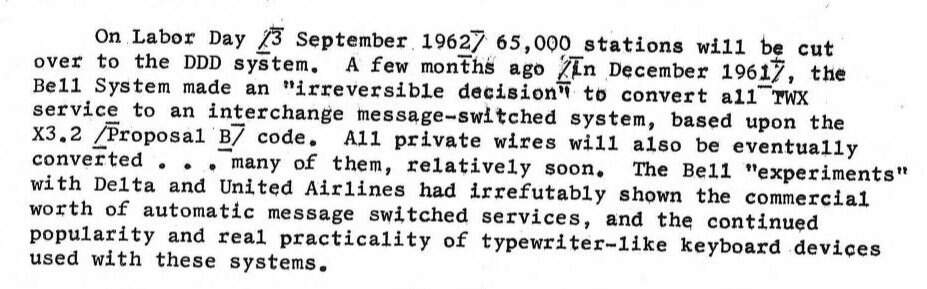

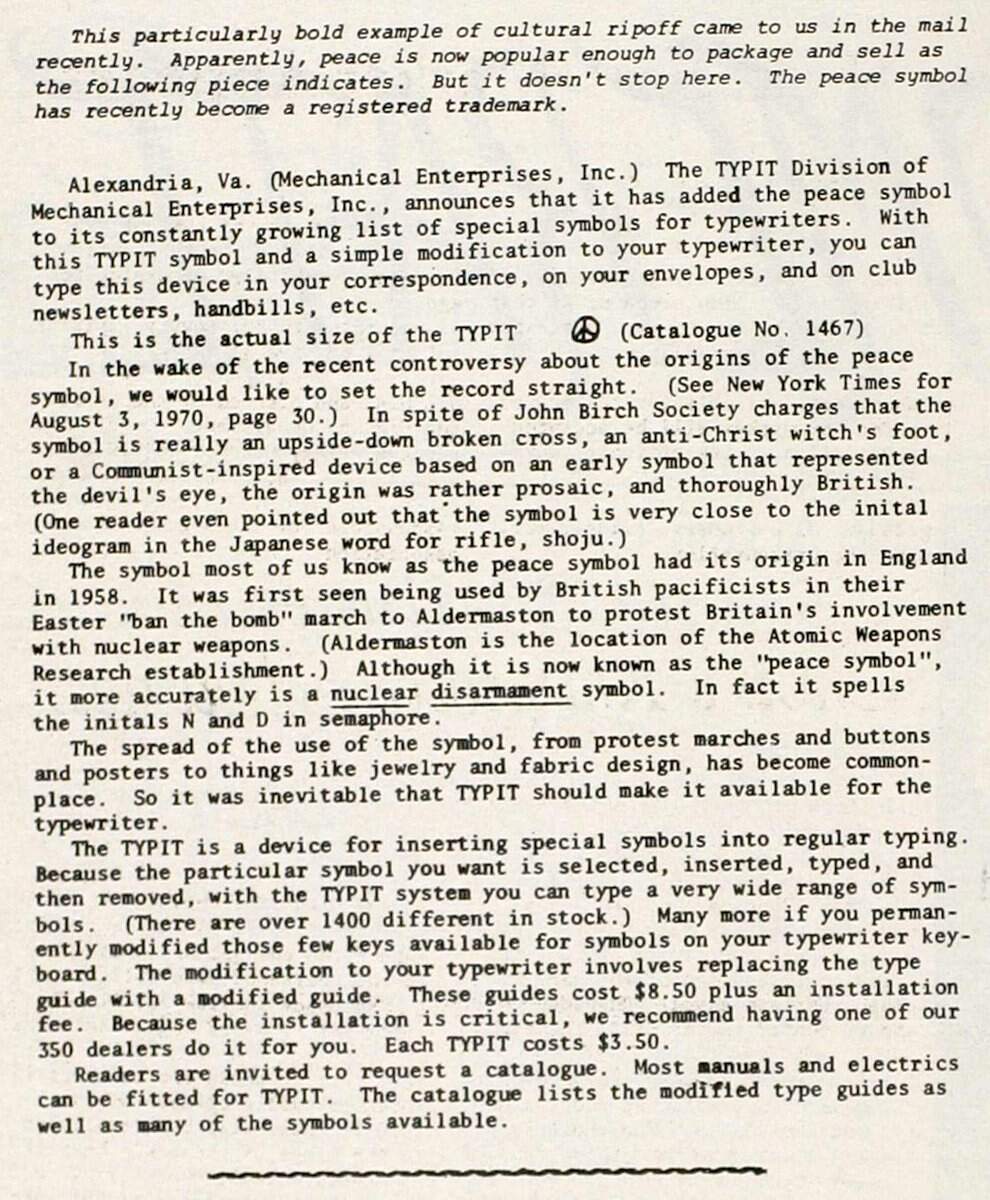

The system was in use in between 1950s and 1980s. I don’t think it was very popular, despite many ads in electronics, chemical, and other scientific periodicals – and despite some marketing gimmicks, like this one from 1970.

There was even Typit II, actually compatible with the Selectric ball typewriters, a font-swapping tech coexisting with a character-swapping one.

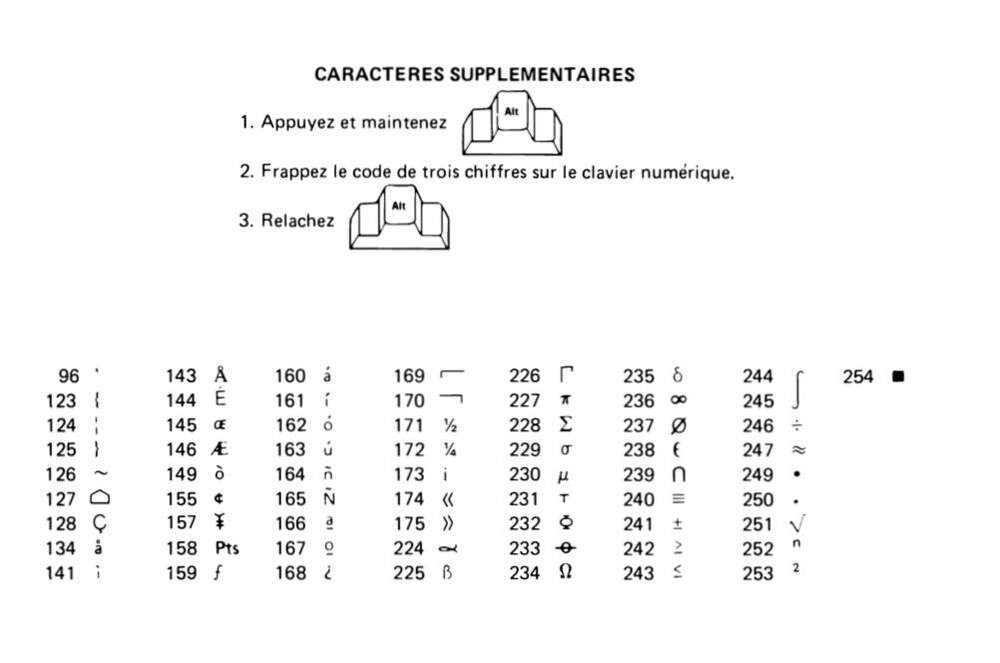

Eventually both, and all the others, were undone by computers which allowed for 31 characters, then 63, then 127, then 255, and now god knows how many via Unicode.

Early on, it happened did with Alt+numeric keypad combination (still works on Win – and Mac after enabling it)…

Early on, it happened did with Alt+numeric keypad combination (still works on Win – and Mac after enabling it)…

…and then via graphical user interfaces and touch screens.

But that’s a whole different story.

But that’s a whole different story.

I love that Typit existed. It’s such a weird hack, and a clever way to solve a particular problem. It’s kind of like a Chrome extension or a Greasemonkey script for typewriters, once again blurring the lines.

And speaking of which, I like it for one other reason:

And speaking of which, I like it for one other reason:

It is a proof that “press any key to continue” existed in the world before computers.

(BTW this thread is dedicated to the hard work and inspiration that is @shadychars.)

(I realize now that I forgot to do the most important visual juxtaposition – and notice that even the sizes of both containers are rather similar!)