My friend showed me around the Muni Kirkland bus yard. Muni is the municipal public transit system serving the city and county of San Francisco. It will turn exactly 100 later this year.

The Kirkland bus yard, near Pier 39, is one of the smallest and oldest bus yards in San Francisco. It is dedicated solely to diesel buses running mostly neighbouring lines, and some express routes too.

There are typically over one hundred buses leaving this yard every weekday morning for the rush hour; I visited on the weekend, when it was much quieter and many of the buses were still on site.

The newest buses here are about 12 years old. This is a typical view of the driver’s area in such a bus, including a pretty comfortable, customizable seat.

Here I am pretending to be a driver of an older type of a bus. I could start the engine (no key required!) and open or close the doors, all with my left hand. What’s not visible here is a collection of carefully positioned mirrors allowing me to see all the way through the end of the bus, and even inside the rear doorway.

This is the lever used to open the doors. The first position is Front door open, rear unlocked—since recently Muni started allowing rear-door boarding (if you have a fare card), there is another switch further down the console to force the rear door to open whenever the front door is opened.

This is a close up of the left-hand side. Textual descriptions of buttons strike me as very American; I’d imagine a similar panel in Europe would use mostly pictograms.

Some of the drivers extend more commonly used switches with cardboard so they’re easier to locate without looking. The cardboard comes from the back of the pack of transfer slips!

Another hack: since buses will shut down after eight minutes of inactivity, the brake pedal is sometimes propped with the wheel chock if the engine needs to idle for longer.

Driver’s left foot is used to control turn signals, P.A. system (middle switch), and head lamp dimming (the one farthest to the left). Each button has to be held continuously to work (which is known as a “dead man’s switch”).

The controls for the wheelchair lift are a bit sophisticated in this older bus—some buttons have to be held together, some others have a protective housing. It all eerily reminded me of WarGames.

Also, check out the bike rack indicator in the upper right corner. It lights up when the bike rack is down, although that should be easy to see for the driver since the rack is right in front of the bus anyway.

Wheelchair lift controls on newer buses—the knob in the bottom right on this photo—are simpler. The transfer cutter above is many a decade older. Also, note the rubber band in between the controls which the drivers use to put pieces of paper (for example their schedule) behind.

This is the device controlling what’s shown on all the digital marquees, and what’s being announced as the bus arrives at various stops. After the driver chooses a certain line and variant (direction) of the line, everything else is automatic.

The data and voice recordings are held on a local memory card and need to be upgraded on all the buses by hand whenever routes change.

I immediately asked if we could see all the “special” routes and I learned that, given it works for the city, Muni needs to be ready to perform all sorts of special functions, for example transporting the police!

I also saw ambulance, all sorts of events, generic destinations (e.g. San Francisco), and temporary replacements, for example for cable cars. There is also a pixellated version of the Muni logo, affectionately known as “worms.”

A view of the Kirkland yard from inside of the bus. Only diesel machines are here—newer hybrids and “artics” (articulated, or long, buses) belong elsewhere.

The back of the bus. You can actually start the bus’s engine from here if you know how! Deep inside there’s also a little fire extinguishing system that sometimes works, and sometimes doesn’t (it activates whenever the fire burns through a special cable’s isolation). Speaking of which, the bus catching fire and burning completely is possibly the only way for it to be decommissioned. Otherwise buses live on forever, with all their parts—including engine and transmission—replaced as necessary.

One example of a relatively recent upgrade is the set of catalyzers reducing emissions.

Those catalyzers require a lot of cleaning and maintenance with a special machine…

…held inside a repurposed room.

The whole yard underwent a similar upgrade history as many of the buses. It’s over 60 years old, and an old black and white photo on one of the walls shows its beginning within still a very industrial area. Today, the yard’s surroundings are a popular tourist destination, and perennial rumours suggest moving the buses elsewhere and redeveloping the land.

This still-operating 1970s computer with 8" floppies confirms the age of the yard.

If that didn’t convince you, how about this sign?

There is still machinery here that no one ever uses anymore and many people wouldn’t even know how.

Also, some vintage typography…

…followed by some more modern jokes.

This is a typical preventative maintenance schedule. Today, six highlighted buses will undergo a 1K inspection, which happens when their mileage hits one thousand (more or less every two weeks). There are many other types of inspections too.

In addition to scheduled maintenance, the yard also does some emergency repairs. Apparently, the most common defect is the doors and the wheelchair lifts breaking. (The doors are rather sophisticated; there are many hidden sensors to detect whether a person or one of their appendages are not too close to the doors.)

This bus’s radio broke and it awaits a mechanic. Generally, if you walk past a yard, the rule of thumb is—buses facing the exit are ready to go, buses facing the other way need to be repaired or checked first.

This is one of the pits that could be used to access the bus’s undercarriage. The pit is now covered to prevent injuries.

Bus number 8222 is being worked on right now; all of those hoses supply various liquids and air.

Inside of the pit is rather filthy and there’s not much room, not even to stand up properly.

Instead of using the pit, the bus can also be raised in-place using lifts like those here. That’s quite impressive, given a regular diesel bus weighs 24 tons!

This is a close up of two of those lifts that go under each wheel and are synchronized with a cable.

The buses also need to be cleaned. Apparently, of the routes served by this yard, line 19 buses get dirty the quickest.

Inside the spare parts room, we find an old-school route number decal, no longer in use.

There are also tons of replacement stickers.

Including this one, recently decommissioned. (Boarding through all the doors is common in Europe, and it’s slowly making its way to America.)

There are huge diesel tanks under the surface of the yard. Again, Muni is required to have those tanks be refueled daily so that they can help other municipal agencies’ vehicles in case of an emergency.

Some sticks to measure the transmission fluid levels.

All sorts of labels to be put on the buses requiring work.

The whole maintenance part of the yard is, as you can expect, quite a bit industrial. There is also the operations part and a separate building where drivers get to hang out before their shift begins and after it ends.

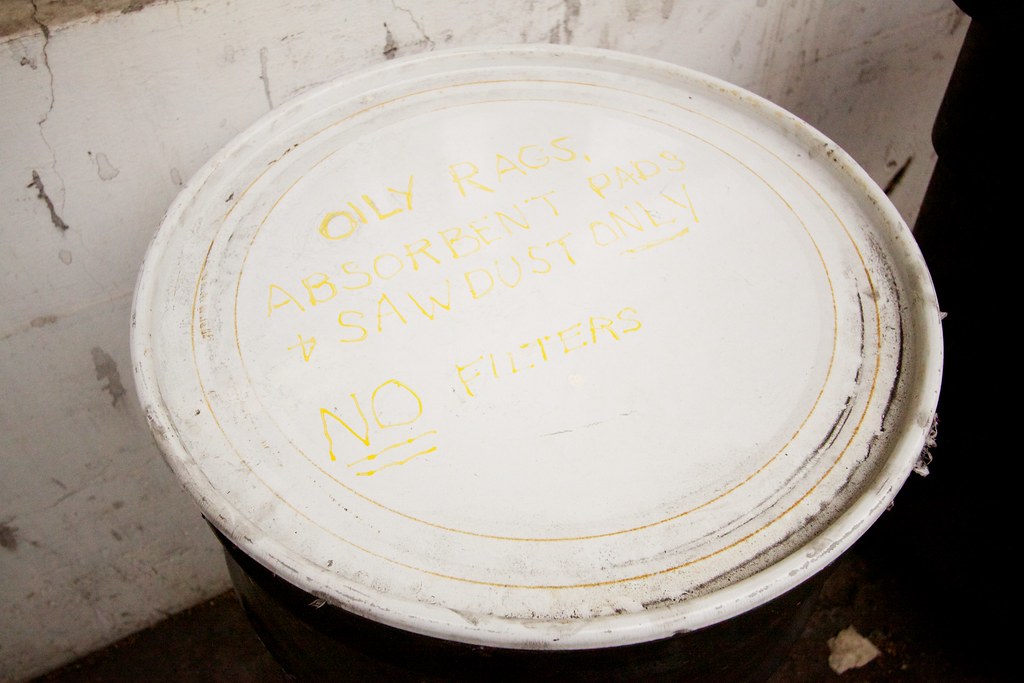

This is an older room in the maintenance building.

On the way out, we intercepted one of the drivers and helped him find his bus. In his defense, it seems hard—the whole place is like a maze!

The whole tour was a lot of fun and a fascinating look into how much care and attention is required to keep Muni buses running—something we all probably take for granted.