Marcin Wichary

December 2023 / 3,100 words / 35 photos

Originally published as a booklet accompanying Shift Happens

The day Return became Enter

In the popular imagination, the transition from the world of typewriters to the universe of computers was orderly and simple: at some point in the 20th century, someone attached a CPU and a screen to a typewriter, and that turned it into a computer.

But the reality is much more fascinating and convoluted. The transition was meandering and lengthy, and traces of its many battles and decisions remain scattered across keyboards today. And no key might better represent the complexity of that journey than the Return key.

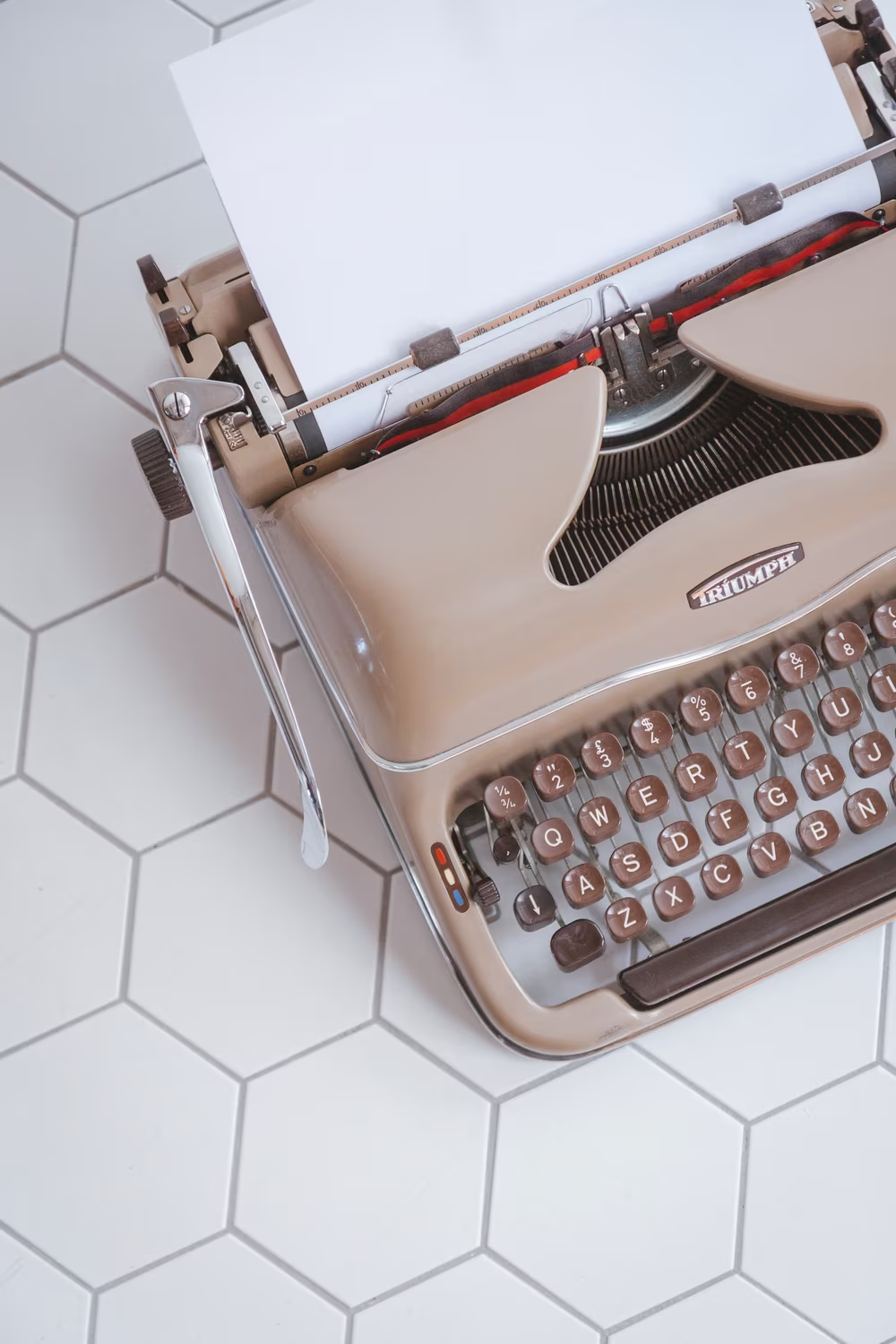

Typewriters, born in the 1870s, did not understand information, and didn’t care about the meaning of their output.

Early models lacked 0 and 1 keys for cost cutting reasons. You were supposed to type a capital O or a lowercase l instead – they looked just about good enough. Teachers and tutorials encouraged you to overprint to create missing characters: type I on top of S to get a dollar sign, for example, or even reach for a pencil to fill in a missing part if overtyping wasn’t good enough. In theory, you could go even further: nothing prevented you from grabbing a typewritten page, putting it back upside down, and typing on top of what you wrote before.

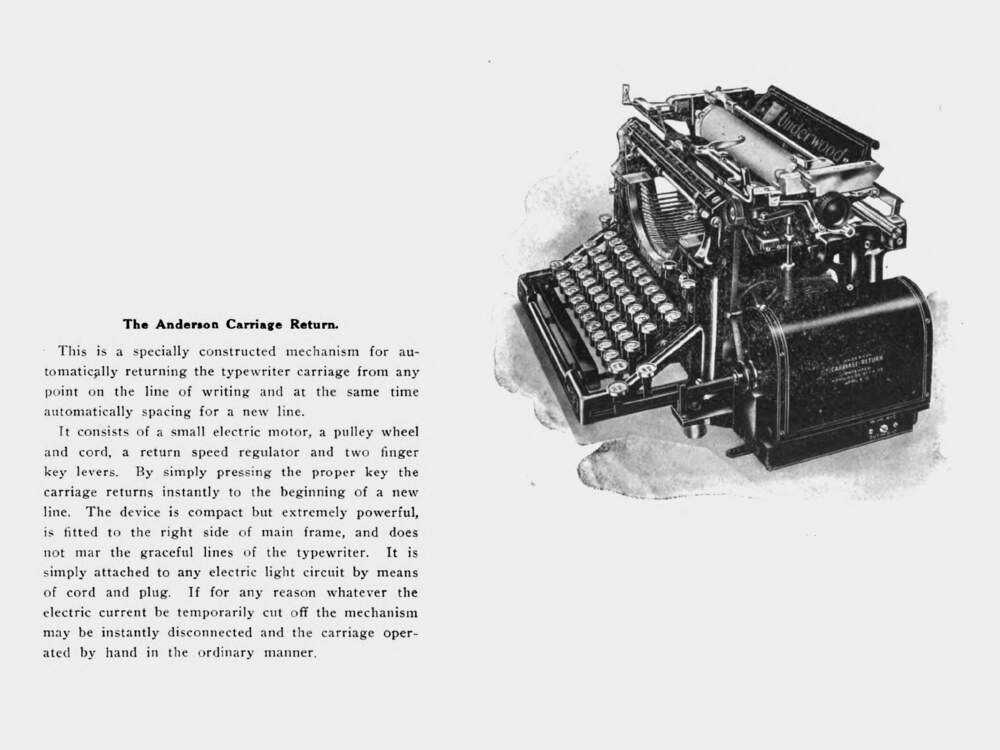

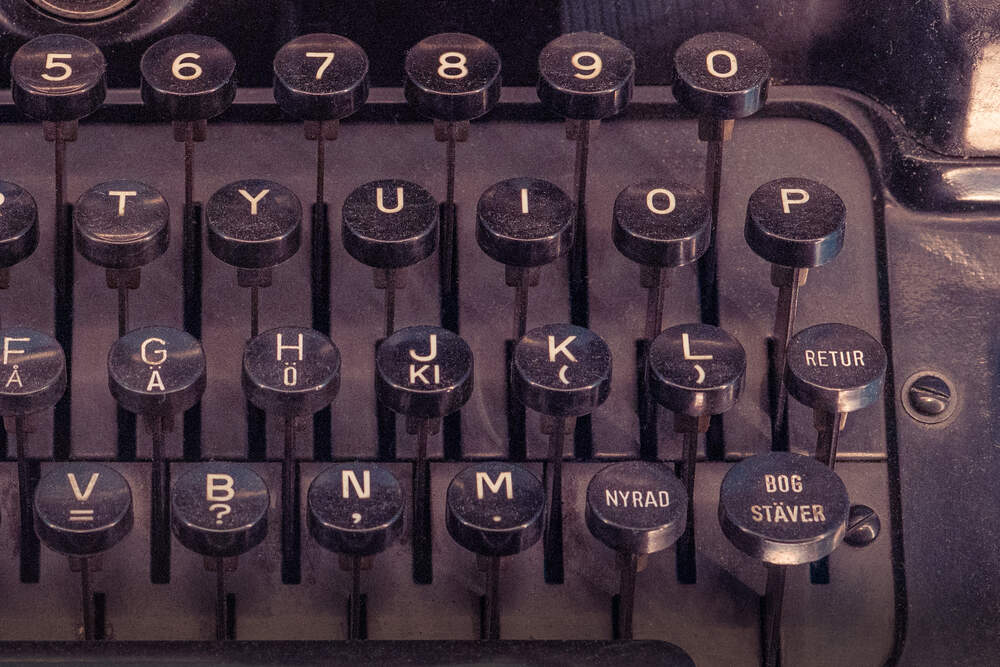

In that universe, a carriage return – that distinctive lever on the left-hand side of each typewriter – was a kind of mechanical shorthand. It advanced the paper by a line or two, and returned the carriage to the left margin, winding it for the next line. You could carry out those two functions separately, but even early typewriter manufacturers realized the operation needed a better, joint interface.

The carriage return lever was similar to all the other mechanical functions of the typewriter, starting as simple as humanly (and inhumanly) possible. Tab added a few spaces or mechanically zipped the carriage to the next predetermined point. The Shift key moved the carriage up or the key basket down, applying its simple operation to every key equally. Shift Lock was a literal tooth holding Shift in place, placed right next to it for manufacturing convenience first, and ergonomics a distant second. It affected letters, digits, and punctuation in equal measure, in contrast to the later Caps Lock.

Some of these special keys started as levers or even, like Tab, first-party or third-party additions bolted onto your typewriter. In time, all these functions migrated to the keyboard, making them easier to reach and more consistent in their operation. But carriage return remained the one holdover, too mechanically complex to follow in the other functions’ footsteps.

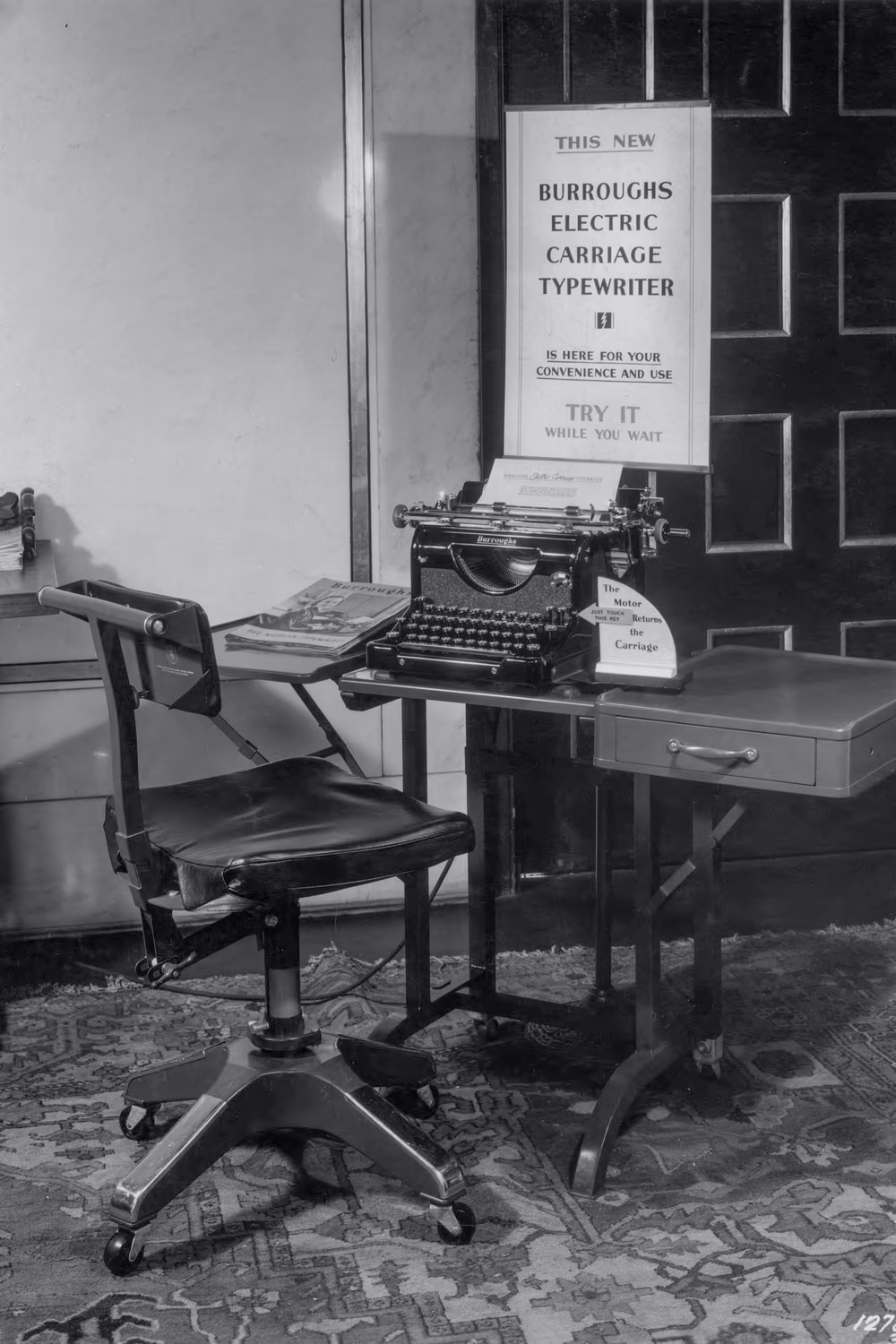

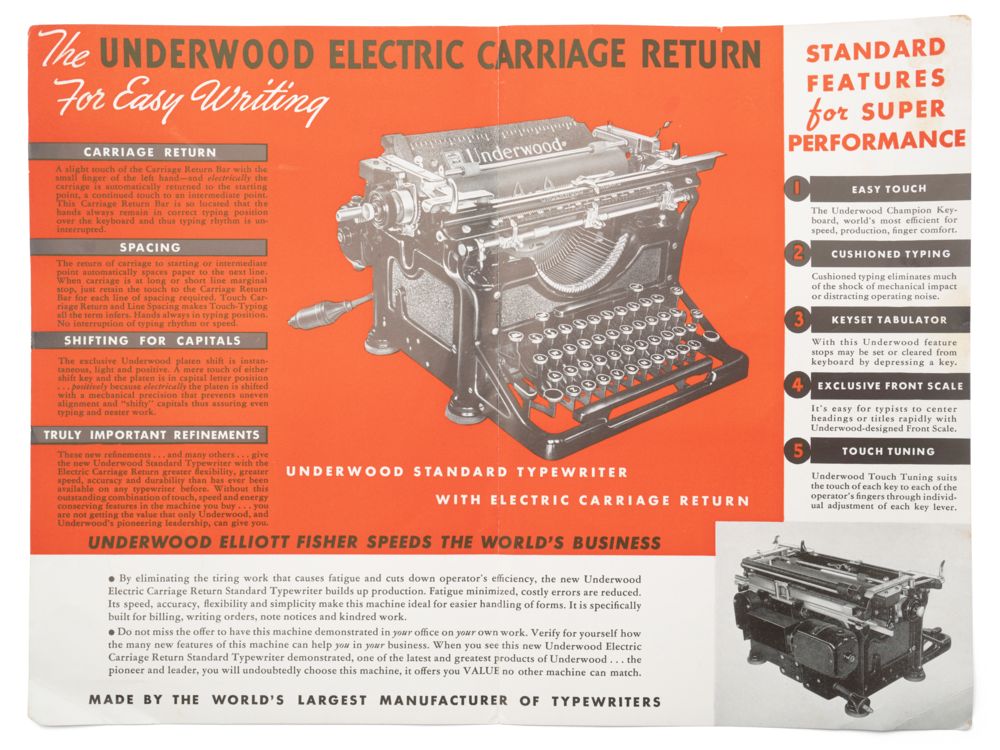

It was only when typewriters embraced electricity in the 1940s and 1950s that the carriage return completed its transformation into a key, and the distinctive lever could be detached.

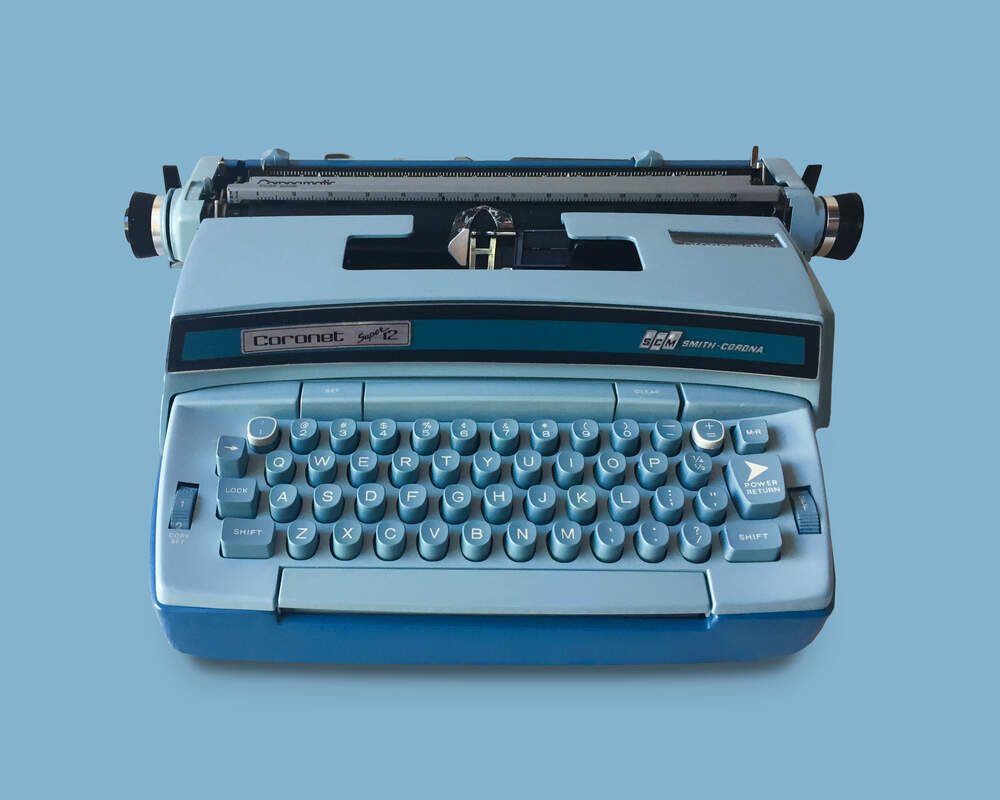

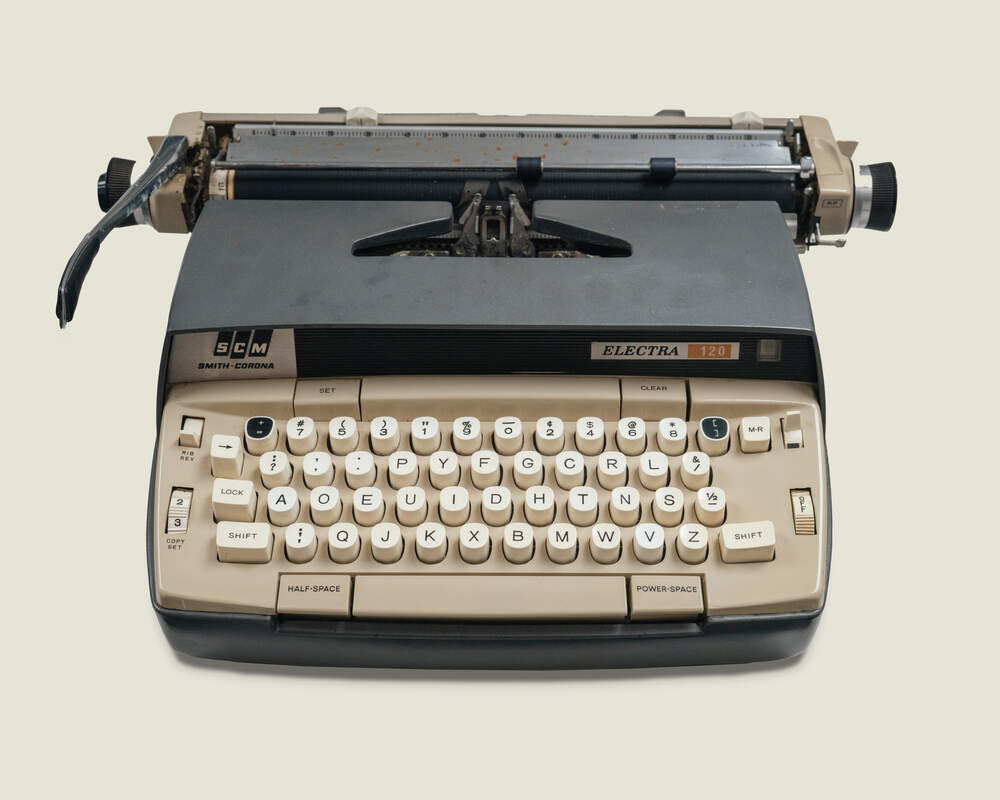

The key was most often called Carriage Return or Return, as expected. But since introducing electricity made the carriage return so much easier to operate, it was no surprise that the industry that once brought you Floating Shift and Magic Margin keys also saw some typewriter manufacturers calling their keys Electric Return or even Power Return, like doors in your shiny new Detroit-made car.

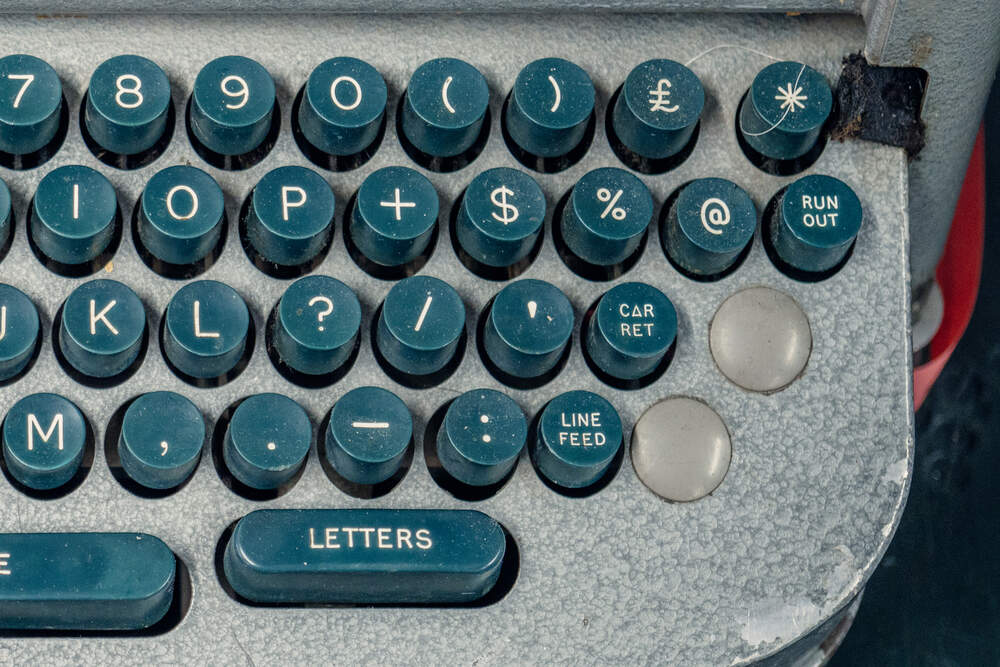

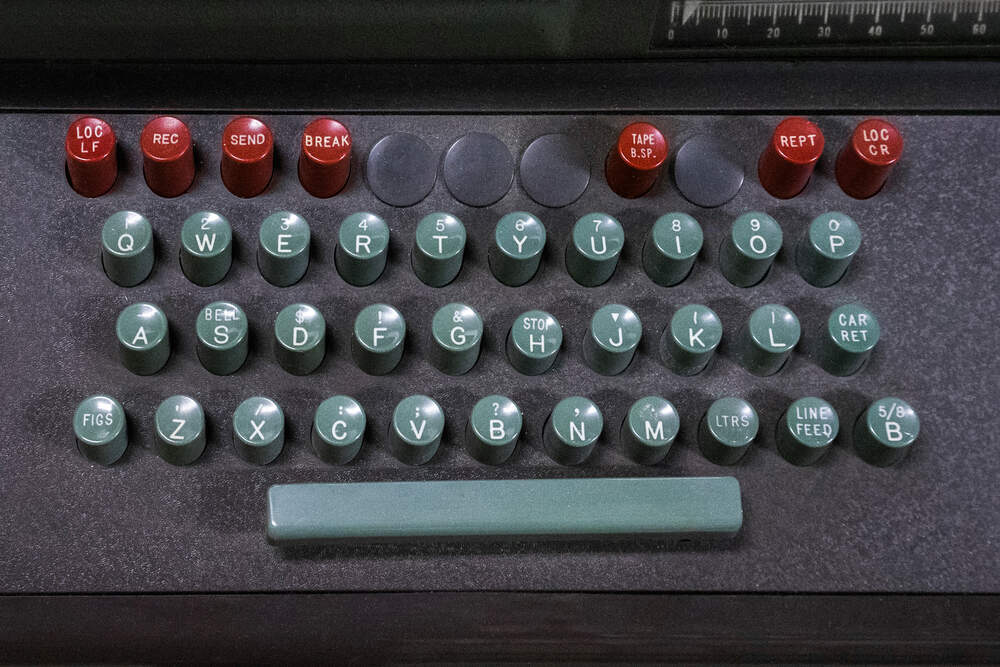

But there were other keyboards that embraced electricity even earlier without bragging about it. Those were the keyboards of teletypes, taught to send text across wires (“teletype” derived from “teletypewriter,” or “remote typewriter”) at a constant speed of a little over 6 characters per second.

Teletypes formed pre-internet information networks, used by news agencies, postal offices, railroads, and other big companies and institutions. They were a successor to Morse code, abandoning its iconic single key that was pressed repeatedly to create streams of dihs and dahs. What replaced a Morse code lever was, at first, the five-key Baudôt keyboard, and then a standard typewriter-like QWERTY keyboard, the general public’s familiarity with which ensured less training was required.

Using a QWERTY keyboard meant the machines had to be tasked with encoding. Every key was assigned a number from 0 to 31. Space was zero, A was 3, B was 25, C was 14, and so on – teletypes knew how to encode all of the characters being typed in, and how to decode them on the other side.

But for proper operation, it wasn’t just letters and digits that needed to be transmitted. Everything else – spaces, backspaces, jumping to a new line – also had to travel across the wire, to make sure the reconstructed message matched the input like a carbon copy would.

Those extra pieces of information were eventually named “control characters,” and assigned their own codes. But there was a problem. Typing a letter, moving back, and advancing paper took relatively little time. However, zipping the carriage from the right side of the page to the left was slower. That created a challenge: since teletypes communicated at a constant rate, the first letter arriving after a longer line could be smeared across the page, as the carriage return was still in progress.

Just as with early typewriters, any “smart” solution would be prohibitively complicated or expensive to make. But what if the character following a carriage return was guaranteed to be non-printing? This would give the teletype a chance to catch up. And so teletypes undid the early convenience of typewriters, and Carriage Return became decoupled from Line Feed. The former key moved the carriage to the left, but stayed on the same line. The latter advanced the paper to the next line, with no horizontal movement. Sometimes, the Line Feed code would arrive after a carriage return was complete. Other times, it would come in the middle of the carriage returning, but the teletype could deal with those movements coexisting.

The responsibility now rested on a typist to press these two keys every time, and in that particular order. This was a solution to a weird challenge that was both smart and dumb – and it was the first, but far from the last, complication around Return.

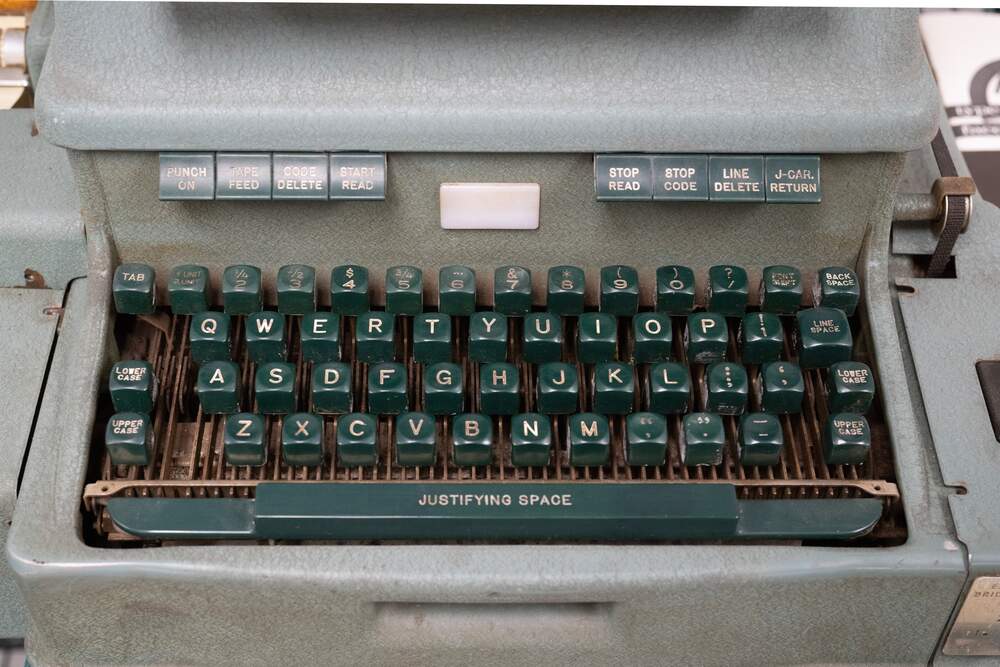

In another corner of the typing universe, the word-processing revolution was brewing.

Early word processors – back when that phrase meant hardware, not software – were nothing more than automated typewriters, teletypes without wires. But they focused on solving a slightly different issue: not one of exchange of information, but one of copying and rewriting.

The first word processors allowed people to “save” a page’s worth of keystrokes that could later be replayed. The letters were initially stored on hole-filled cards – not dissimilar to player pianos – and later captured onto magnetic media. The automatic repetition had two huge benefits: You could create carbon copies that were of the same quality, and you could also create personalized advertising letters, ones that looked as if they were typed just for the recipient.

After mastering that, the inventors of word processors moved on to the next, even bigger challenge. With typewriters, making a single typo or having a belated desire to change anything usually meant throwing out what one had typed so far and retyping the page from the beginning. But what if new technology allowed you to freely modify the saved text? Would it be possible to replace one word with another? Or delete a word? Or insert a sentence?

There were many, many problems to solve here: storage, logic, user interface. One of them? The naïve carriage return struggled to find its place in the world of word processing. What was necessary was text reflow: automatically adjusting the text and inserting carriage returns (or even hyphenating) whenever a word was about to go past the right margin. And then revisiting those breaks the moment anything was changed, inserted, or deleted.

Early text reflow happened before screens, arrow keys, and cursors became ubiquitous, so the user interface was a bit more cumbersome – you couldn’t preview what was happening until you printed. But it was also a revelation. Word processors allowed for rewriting without retyping, saving people from millions of unneeded, mindless, RSI-inducing keystrokes.

But text reflow required a hard adjustment: in time, every typist had to restrain themselves from pressing Return when the carriage became close to the right edge, and allow the machine to move to the next line instead. Manual hyphenation was not advised, either. The Return key was still useful, but it was now reserved only for the paragraph’s end.

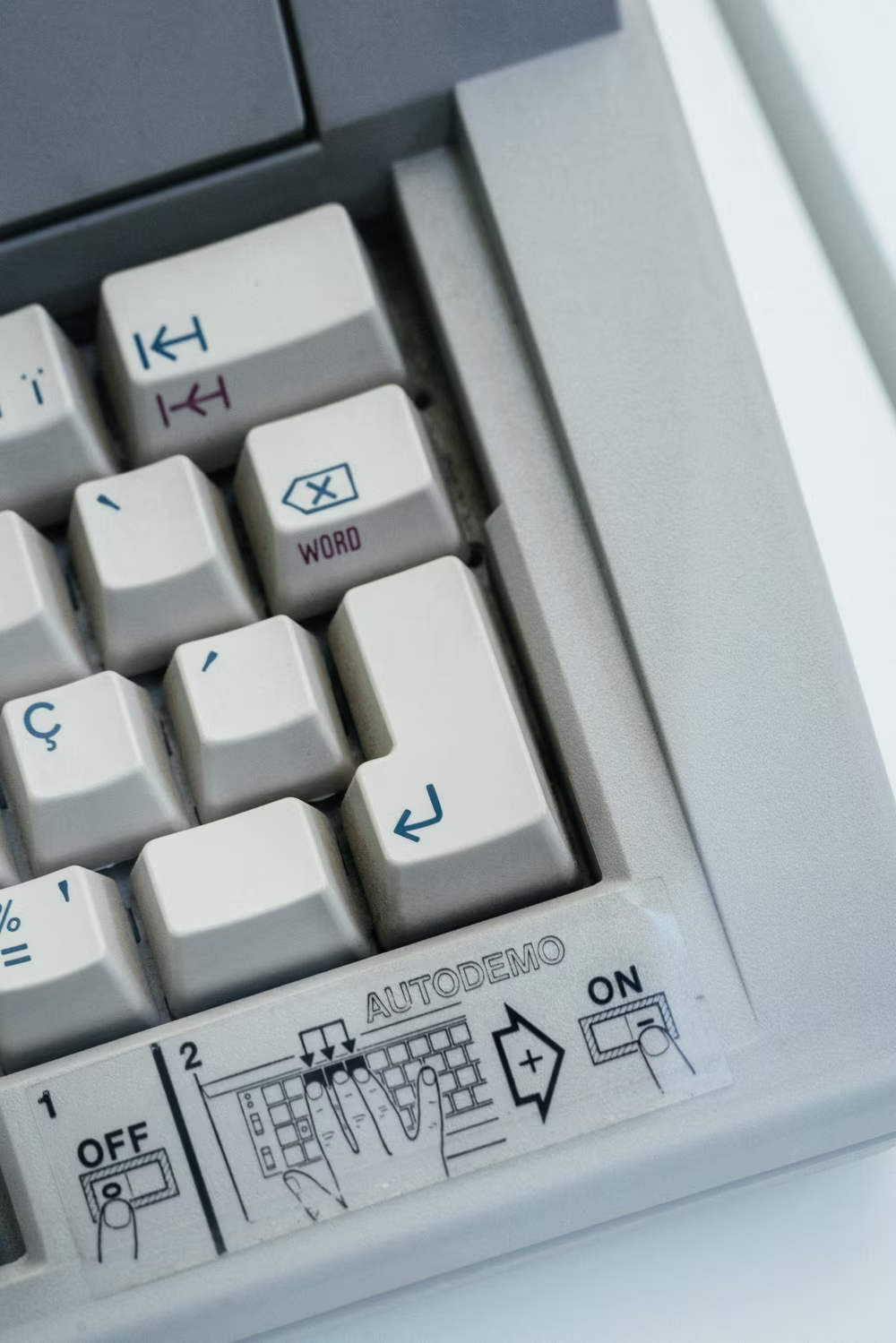

That seemed like a worthwhile adaptation. If only it were so simple, though! You still needed to insert a new line manually for things like tables, addresses, and poetry. Word processors had to introduce concepts like required returns, soft returns, hard returns, cursor returns, line breaks, new lines, and word wrap – which didn’t initially happen automatically as you typed!

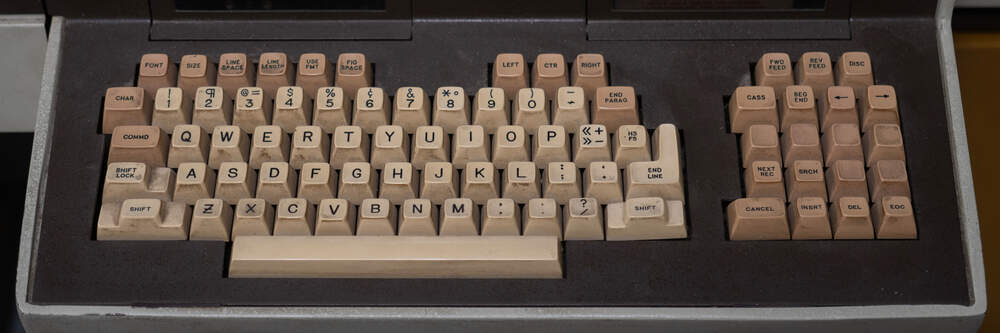

The simple act of pressing Return became more complicated. Sometimes the two kinds of endings became two separate keys, sometimes one that changed its nature when a modifier key (like Code) was held, and sometimes an option within the user interface.

Even electromechanical word processors that arrived before electronics became commonplace soon started to feel like computers: precise, unforgiving, literal. If word processors bragged about introducing the concept of WYSIWYG, they also took away a different “what you see is what you get”: the direct connection between typing a key and immediately seeing the output on a page. Text was now information – data that was infinitely malleable and needed to be approached more abstractly.

Zero and the letter O might have still looked the same still, but now you had to consider their semantics. And even if on the page the old-fashioned line Return and the new-fangled paragraph Return felt like they were performing the same function, you had to imagine what could happen to their effects in other circumstances – what if you printed on a smaller page, edited parts of the text, or reused it in some other way via copy and paste – and act accordingly. Today’s web designers talk about responsive design that accommodates various devices, screens, and zoom levels. In a way, word processors’ redefinition of Return was its very humble predecessor.

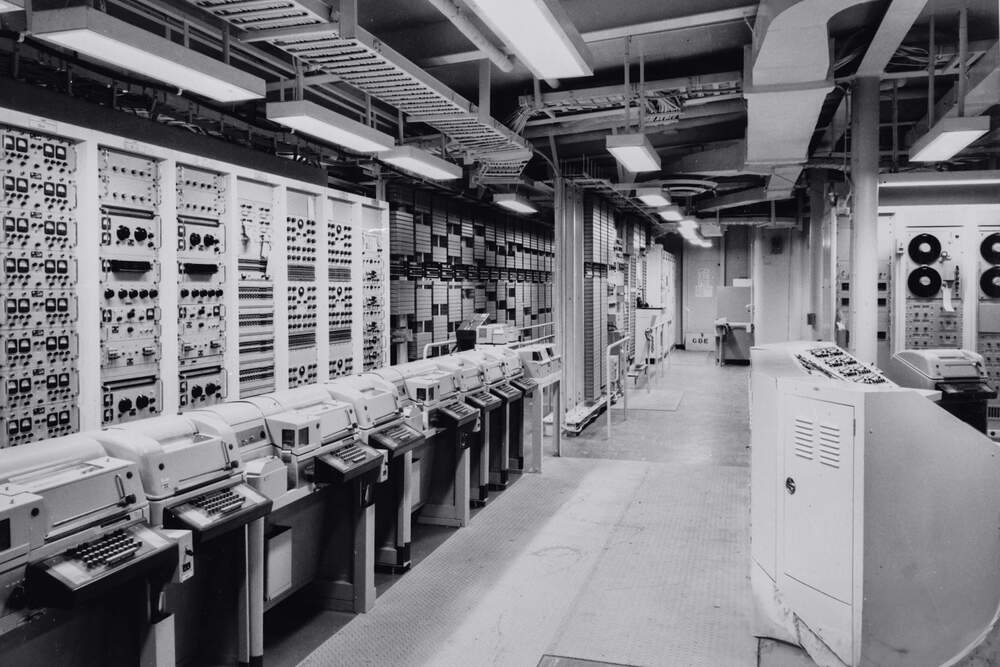

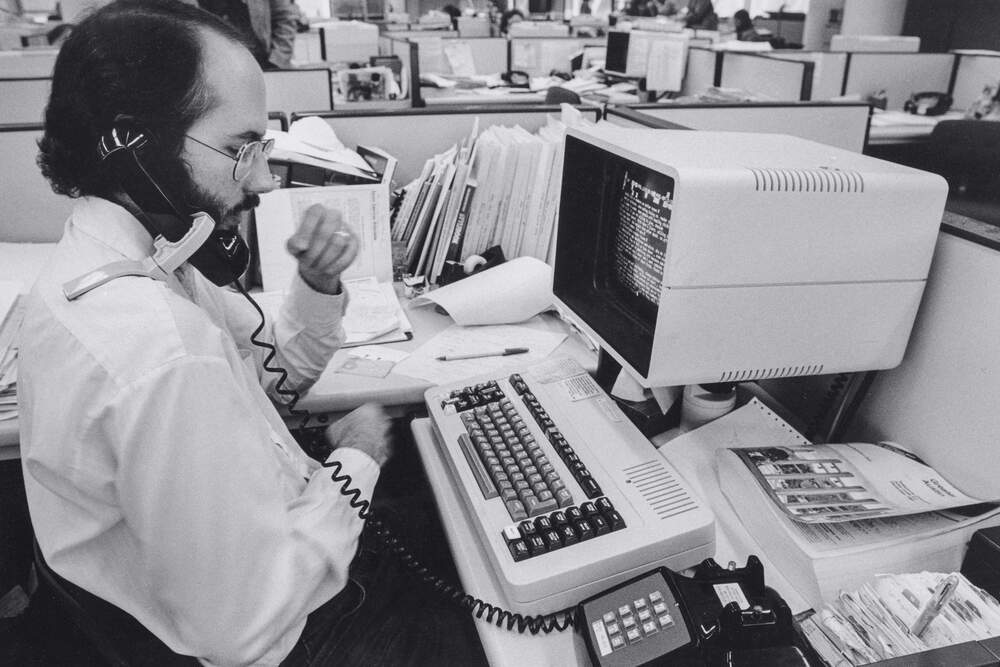

If early word processors felt like computers, late 1970s and 1980s word processors were computers, specialized and dressed up for one and only one purpose in mind. However, other computers had already been around for a few decades by that point – some scientific ones, some enlisted in the military, and some processing vast amounts of information like payroll or census data.

The world of computers began later than teletypes and word processors, but moved much faster. And after an early era of cables that needed to be reconnected, dials that had to be turned, and other peculiar user interfaces, computers too realized that QWERTY keyboards were a uniquely great device for fast human-machine communication.

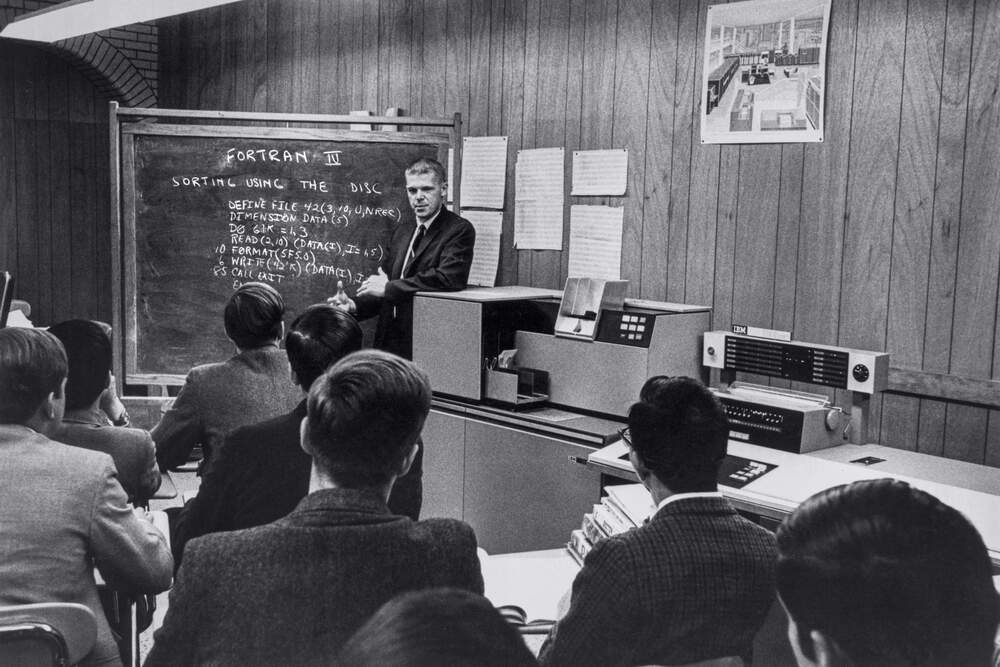

Most of the keys that were part of a typical typewriter keyboard made a lot of sense when applied to computing, but those keys weren’t enough on their own – many new programmer-friendly symbols had to be introduced. In the command-line universe where communications with a computer happened one line at a time, the Return label could make some sense. But even then, that felt inadequate to some people. After all, the act of the carriage or cursor returning to the next line was only secondary. The main reason to press the key was to execute a just-typed instruction, or to commit the entered information to memory.

And so, some computers replaced the long-lived Return legend with something else: some said Execute, others used Word Rel (word release, “word” meaning a unit of data), and others still opted for Next.

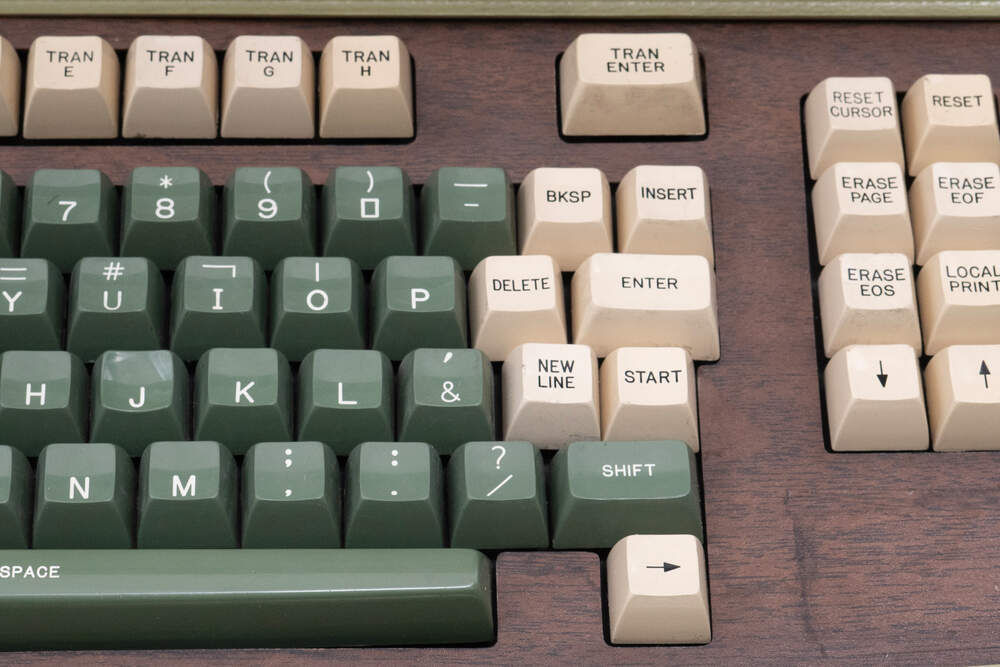

But the most interesting change happened when 1970s computers fully embraced screens, and many interfaces moved away from a line-after-line existence and started resembling forms that needed to be filled in. By then, the technology was powerful enough to not just mimic a typewriter via a command line, but to draw freely across an entire screen. Operators saw a user interface populated with data presented to them one screenful at a time.

With forms came a challenge rather similar to what word processors encountered: There was a difference between returning to a new line within a form field, and the act of submitting – entering – the entire form.

Enter Enter.

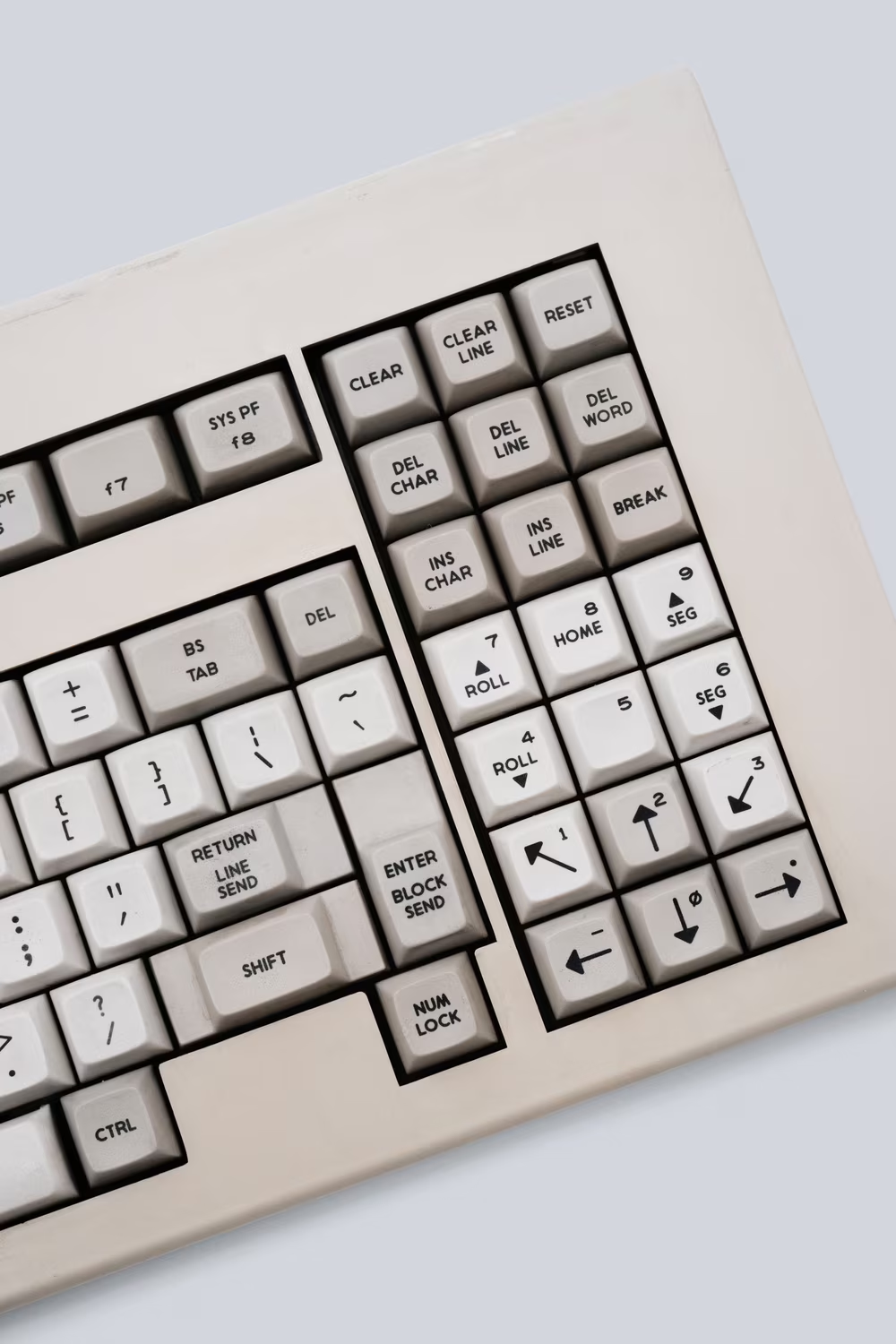

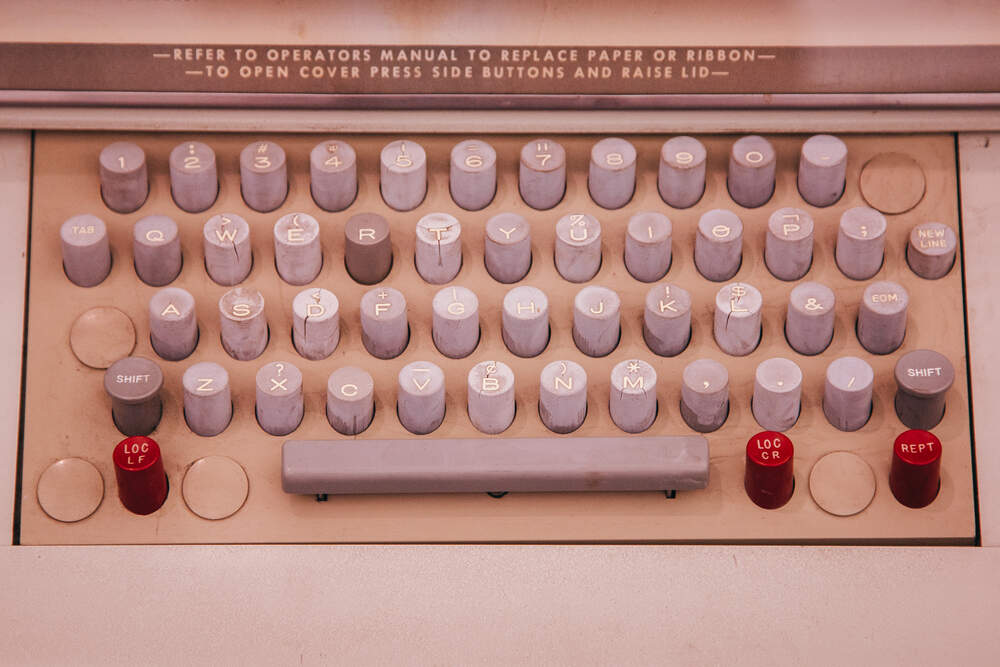

Early terminals made by IBM put the key in interesting places. The IBM 2915 had two Enters in place of Shifts, the latter of which became useless on a machine limited to uppercase letters. Later, hyper-popular IBM terminals, created a setup still inhabiting motor memories of computer operators from that era: Enter to the right of the spacebar, and Reset for system recovery (such as after trying to type in a protected field) on the left.

Now we had typewriters with their line-breaking Electric Returns, word processors with paragraph Returns, and early computers that colocated Returns and Enters – and sometimes rewrote their legends.

Teletypes evolved, too. The early limitations went away as electromechanical and then electronic helpers came to the rescue, and the designers found a way to fuse Carriage Return and Line Feed back into one key, performing two distinct operations under the hood not unlike an old typewriter carriage return lever. But Carriage Return was no longer available as the legend – so a new label was born: New Line. And, on some keyboards, the new function coexisted with the old decoupled ones, potentially creating even more confusion.

To make things worse, the four eras – typewriters, teletypes, word processors, and early computers – meandered, overlapped, and stole from one another. Some early computers used electric typewriters for input and output. Later ones used teletypes. Still others came with completely custom keyboards. Word processors were all over the place as well: some were nothing more than typewriters with extra machinery and keys bolted on to the side, while others were completely custom-made machines.

And the early hobbyist computers from the 1970s? They did everything under the new microprocessor sun. They repurposed old typewriters, reused keyboards of earlier computers – hell, they even borrowed keypads from calculators. Some didn’t even mind now-obsolete Line Feed keys or other detritus.

For a while, it seemed like Enter wouldn’t ever settle down, forever traveling around the suburbs of keyboards. But that all changed in the 1980s.

When proper personal computers came onto the scene with the IBM PC in 1981 and the Macintosh in 1984 – both preceded and followed by hundreds of other machines – they brought with them a point of reflection. The value of PCs was software, allowing computers to turn into whatever you needed the moment a new program was loaded. An Apple II could be a spreadsheet, a word processor, a database, a programming environment, and a game machine to different people – or even the same person at different times of day. And with each coming year, there would be more and more software.

The previously rather specific keyboards had to be made universal. Keyboard designers attempted to solve this via keyboard shortcuts, function keys, and soft keys – all allowed each application to have its own set of operations unburdened by inflexible labels – and by re-thinking some of requirements for the key legends that had to remain.

And the Return key situation was the most dire: What to name the key that could conceivably be Enter or Return or Execute or Proceed or Field Entry or New Line or something yet unknown – all depending on the circumstance?

This was perhaps the moment to come up with a generic universal label – something like Go or Ok. Some computer manufacturers made that choice, indeed, and history would have looked different had they succeeded.

But the keyboards that ended up shaping the future of the industry followed tradition instead. Apple named their key Return on all their nascent software platforms. And the IBM PC – and later Microsoft Windows – went with Enter. (Actually, they first chose the ↵ arrow. However, people in America hated not seeing a written legend. Plus, it’s hard to talk about a key without it having a proper name – as Apple learned the hard way with their ⌥ or ⌘ modifier keys.)

Apple and PCs were both right and they were both wrong – or perhaps it didn’t matter. Most of the jobs of non-typing keys on a keyboard today are much smarter now, and far from their original, often literally mechanical, meaning. Esc no longer outputs an escape code. Tab does a million other things (including some tasks that look very much like what Enter does), and only occasionally jumps to a tab stop. Shift doesn’t shift the carriage. Control does more than just outputting control codes. The spacebar scrolls pages and opens doors in games. Apple replaced the old-fashioned Backspace – a typewriter space that literally goes back – with a more computer-appropriate Delete – but then relented in the late 1980s, and added Control next to Command, ensuring decades of confusion. In the same vein, Apple also added Enter to the numeric keypad, although an Enter that almost exclusively did the same thing as Return.

This is always the tricky part talking about keyboard history. There was no day, no single event when Return became Enter. We’re stuck in a universe where some people use Enter to enter data and Return to return the cursor to the next line – and others do the exact opposite.

For me, there are moments when I wish for two separate keys. My Slack devotes precious screen real estate to explaining the difference between Return (“enter” a message) and ShiftReturn (“return” to a new line without sending), and sometimes swaps those functions around. Other apps don’t seem to agree on the modifier key needed: the videoconferencing Zoom expects CtrlReturn, while Messages wants AltReturn to create a new line. The once hardware variety of earlier keyboards became software complexity.

Luckily, in most other situations, the context is clear: the often strangely shaped key does the most obvious thing, even though its legend might not perfectly capture it. And that makes me think that perhaps the best answer to this conundrum would be to go back to the very beginning. Before Enter, before Electric Return, before even the ubiquitous lever, in the earliest versions of the first QWERTY typewriter, the carriage return was actually a pedal borrowed from a sewing machine.

And sometimes that’s just what I dream of: one, huge, unmistakable key without a name; one that’s simply a giant “let’s go”; one that communicates forward progress; one that cuts through 150 years of history.

But then again, having a keyboard you could simply understand without a long history lesson… Where’s the fun in that?