Marcin Wichary

December 2023 / 8,000 words / 33 photos

The primitive tortureboard

Untangling the myths and mysteries of Dvorak and QWERTY

This essay was originally published in December 2023 as sixth chapter of the book Shift Happens.

1

There weren’t many who hated QWERTY more. To his credit, there was a lot to hate. The layout seemed random, with letters strewn around without rhyme or reason. Watching someone type on it felt painful: fingers flailed wildly all over the place, common letters far away from the home row necessitated more travel, and there were long stretches of one hand doing all the work while the other sat idle. Adding insult to injury, it wasn’t even really that difficult to spot someone using a QWERTY-wearing typewriter. The layout was already so ubiquitous, it was known as “the universal keyboard.”

But he felt it didn’t deserve to be. “It would be difficult to design a key-board over which the hands must travel farther,” he said. There was nothing smart about it; QWERTY “was not arranged on any principle, but resulted from the necessity of humoring the construction of the early machine.” He wanted to build a principled keyboard instead.

Eventually, after much deliberation, he did so. He arranged the most common letters in one row, so the hands didn’t have to leave it except for rarer letters, which represented only 30% of characters typed: “The hands travel over the least possible distance. Almost all word endings are close to the spacebar.” Switching to the new keyboard would save 15% of typing time, and the training wouldn’t take long. The keyboard “can be memorized and high speed attained on it in one-quarter the time required for the Universal.”

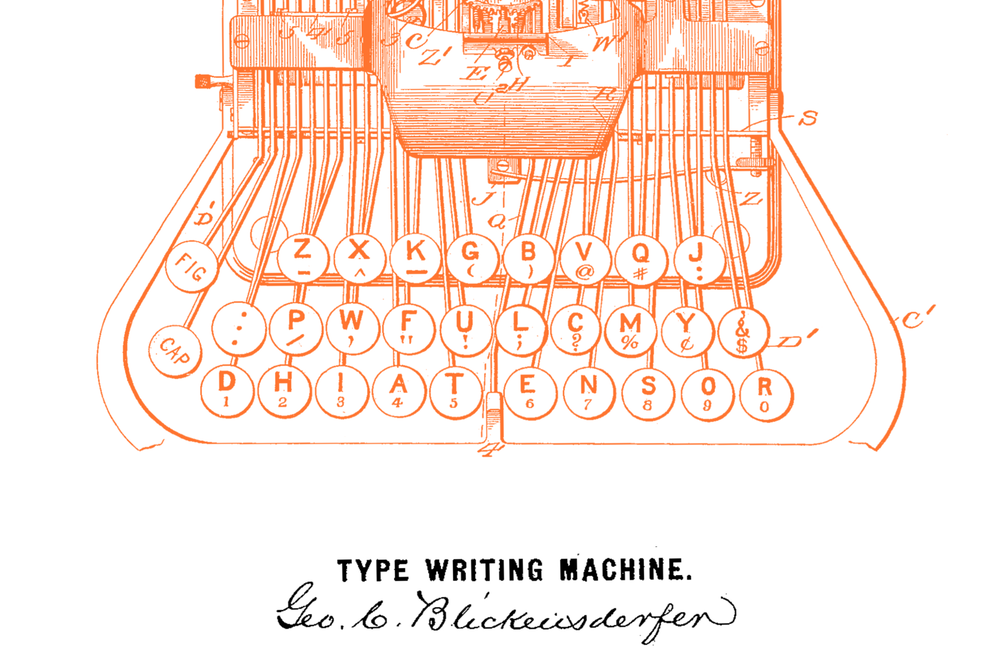

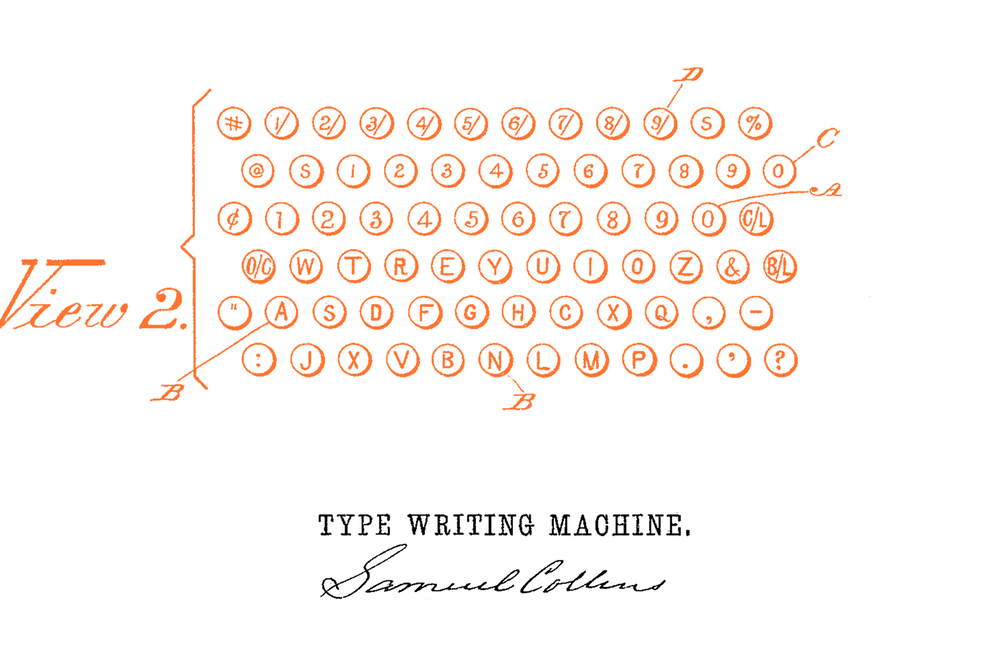

It was a great keyboard with a great layout. He could’ve called it by his name – George C. Blickensderfer – but he had a better one. If the other keyboard was Universal, his would be Scientific.

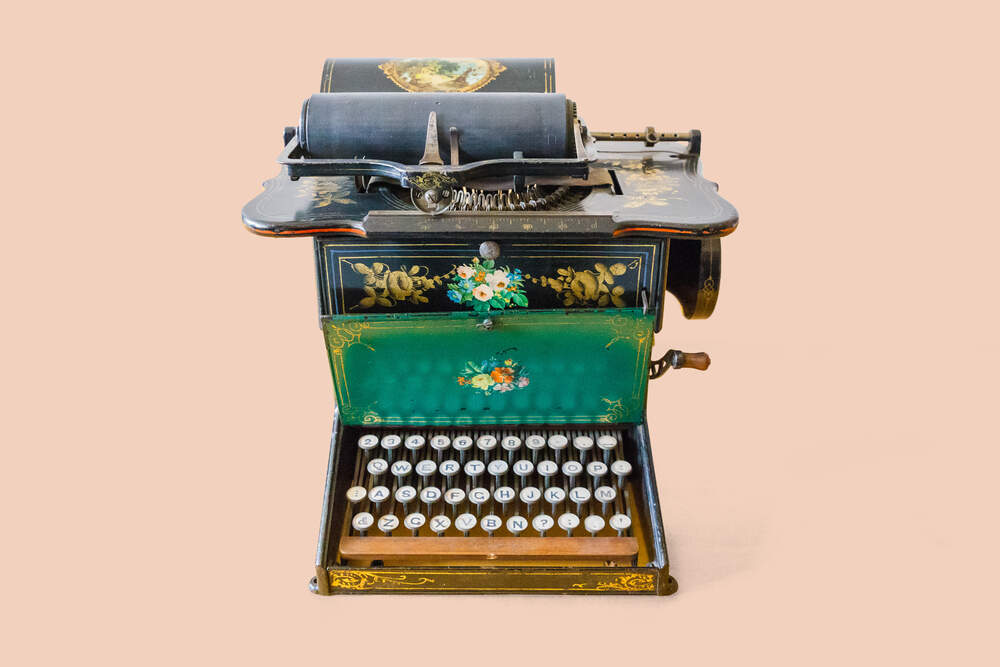

The Scientific keyboard was unveiled in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, attached to a few brand-new typewriters. Those were named after him. Blickensderfer Model 1 was the fully featured model, with some other interesting ideas: an implement for easier line-drawing, automatic word spacing, and extra keys like The, And, and Other that output short words. There was a simpler version, the Model 3, and even the tiny Model 5 had a few interesting features: instead of swinging typebars, it had a type wheel that would rotate when a typist pressed keys. The wheel could be swapped out, which meant you could easily type in many different fonts, and in many different languages.

All three typewriters were fascinating, and Blickensderfer already had a track record of being an inventor that knew how to follow through. But he could not afford more than a small booth at an exposition of twenty-two other typewriter manufacturers – and bad luck would put his right next to Remington’s lavish display.

Little did he know in 1893 that the rest of his career would be defined by bad luck, too. The high hopes for Model 1 never materialized – all the interest and preorders went towards the dirt-cheap, minuscule Model 5. Not that it was bad, of course. The typewriter gained an affectionate nickname: “Blick 5,” or “the five-pound secretary.” It was a bit clumsy, but also portable and affordable. It struck an interesting balance of features and set a price point between cheap, cumbersome index typewriters, and big-featured desktop machines like Remington’s.

Blickensderfer wasn’t done inventing by then. His later, fascinating Blick Oriental could not only type in two alphabets, but one of them – Hebrew – printed right to left. In 1902, he created one of the first electric typewriters in history, the Blickensderfer Electric. And then, there was also the Niagara – a typewriter that produced coded messages, aimed at the lucrative diplomatic and military markets.

In an alternate universe, all of them matured and became product lines that set the tone of the industry for decades. But not in this one. The Oriental was great, but it had limited market appeal. The Electric appeared too early when people were still unaccustomed to electricity. The Niagara’s cipher, advertised as unbreakable and purportedly built over the course of nine years, was cracked within twenty-four hours by a government code expert.

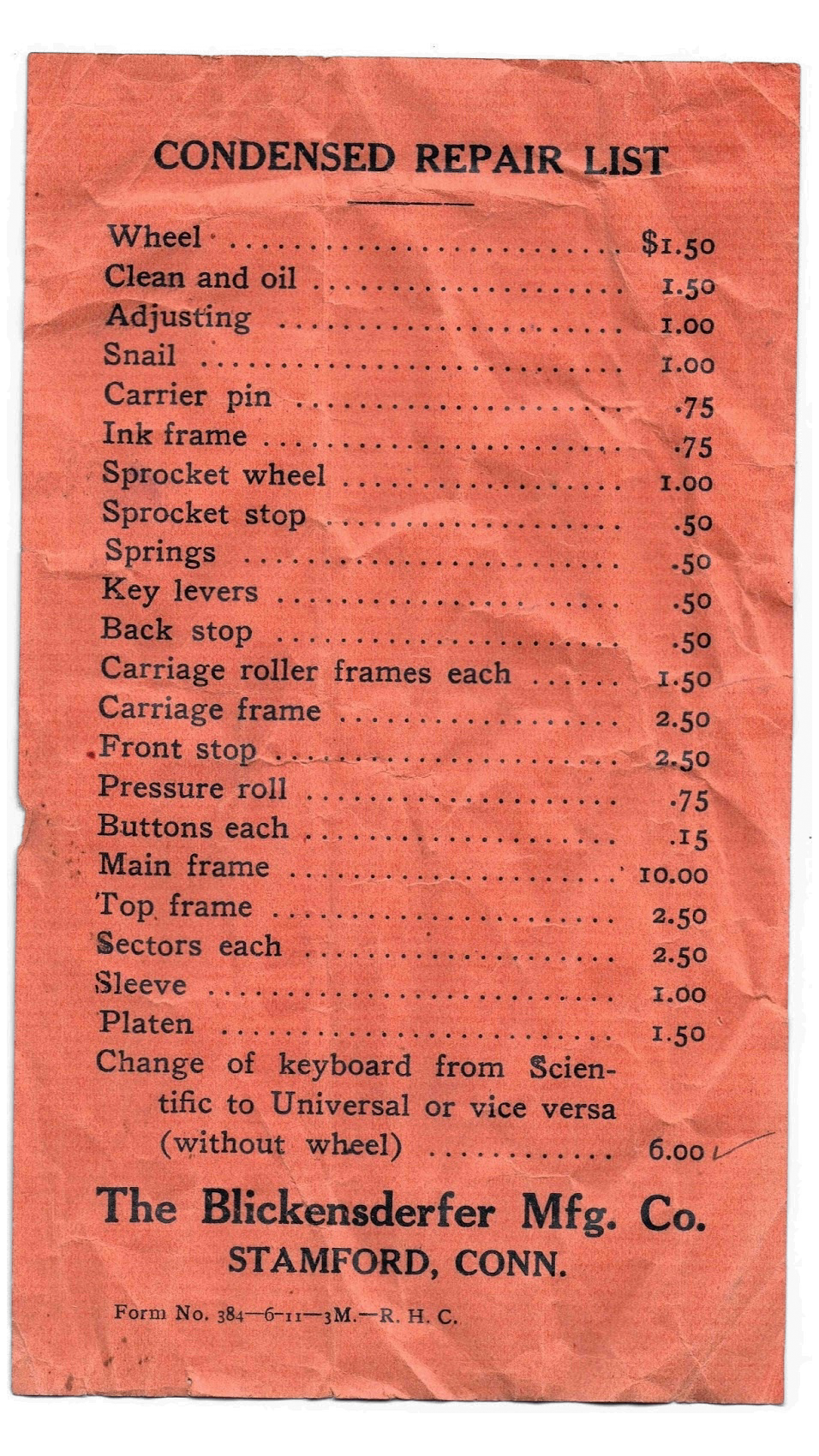

The Scientific keyboard wasn’t having that much luck, either. The layout, also known as DHIATENSOR – named for the bottom row of home keys holding the most popular vowels and consonants right under the typist’s fingertips – proved unpopular with customers already used to QWERTY. Four years after its introduction, Blickensderfer began offering an option to furnish his typewriters with the dreaded, unprincipled universal keyboard. (A rumor started that he even requested such customers to sign a release claiming he wasn’t liable for any bad consequences of using QWERTY.) A few years later, he was forced to go further, offering an option to convert a Scientific keyboard to a Universal for a mere six dollars. This option was presented in the catalog with a wistful and never exercised “or vice versa.”

And even then, Blickensderfer backed the wrong horse, his QWERTY machines equipped with three banks of keys and two rows, a combination already losing the Shift Wars on people’s desks. The adoption of touch typing and the runaway success of the Underwood would soon cement four banks as the only viable option – and just when Blickensderfer introduced that, too, World War I stopped his production and killed all the exports of the prior machines. The final nail in the coffin was a new portable entrant, the Corona 3, that took away most of the domestic market.

George Blickensderfer’s military inventions kept the company going through the Great War, but he himself did not see the end of it. He died in 1917. In the words of one of the historians, his passing “ripped the heart out of the company.” The production of most of the machines ended then. In 1921, Remington, the company whose fair booth dwarfed the introduction of his first three typewriters – and the creator of the Universal keyboard – bought the factory and the patents. After 28 years, the dream of the Scientific Key-Board was gone.

2

Stop me if you’ve heard any of the following claims before. QWERTY was completely random, put together without any thought. Or, if there was any reasoning behind it, it was just putting all the letters necessary to spell T-Y-P-E-W-R-I-T-E-R in the top row, to make it easy to wow customers. How about this version: QWERTY was built to slow the typist down as the early typewriters could not handle high typing speeds, attained by moving frequent pairs of letters as far away as possible. QWERTY was, basically, the worst layout possible. It was built without any ergonomic considerations. It wasn’t great for touch typing.

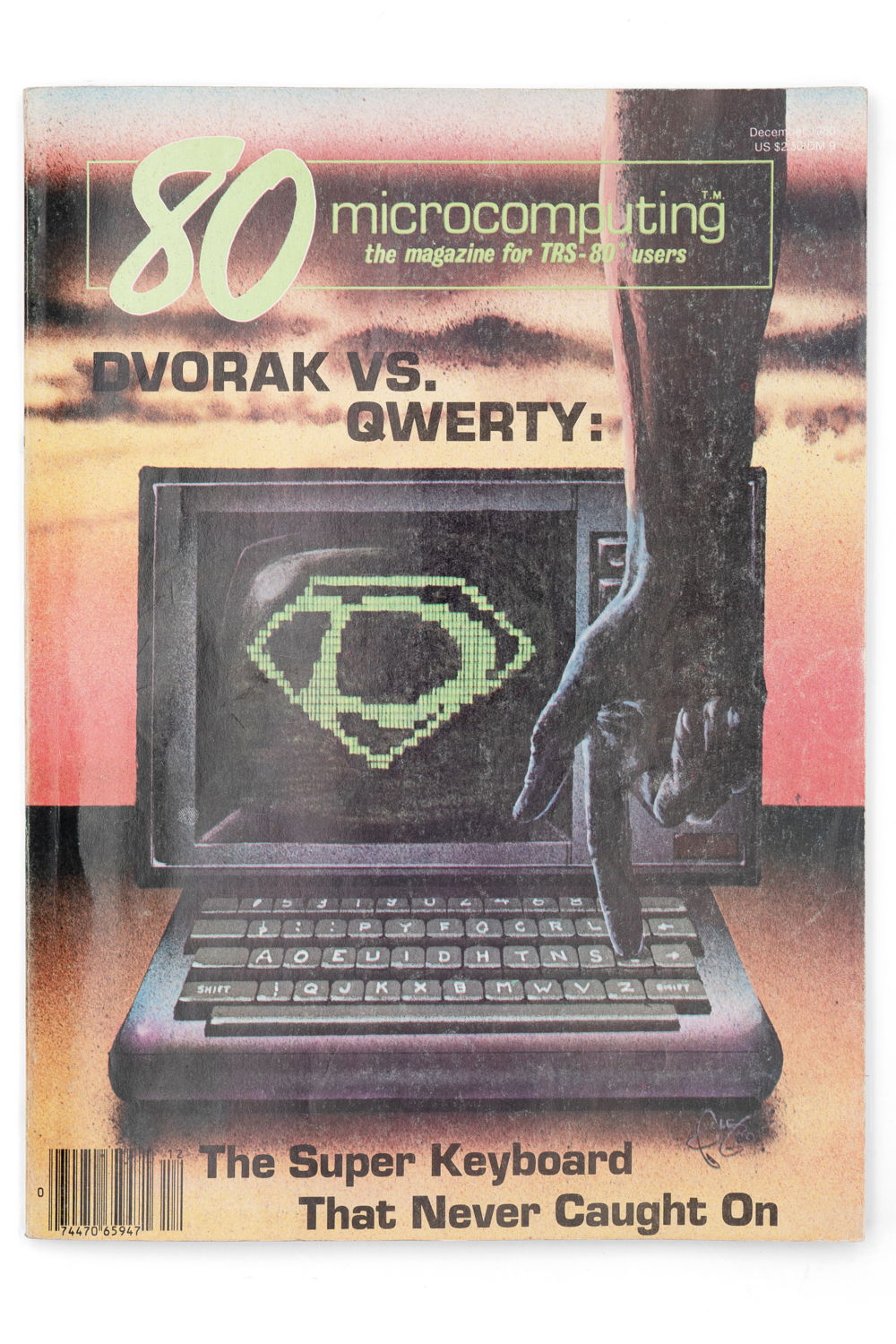

I bet you also heard of the keyboard layout that was the opposite of all the above – the mythical Dvorak keyboard. It was just what Blickensderfer once wanted, only even better. It was the perfect layout, put together with thought and care. It was efficient and comfortable. It was made for touch typing. It allowed the typists to reach 180wpm, fast enough to write down people’s words as they were speaking. But it wasn’t undone by bad luck – it was sabotaged by typewriter companies and typewriter teachers. Or, if it wasn’t, it was still better than QWERTY, and the market treated it unfairly. The fact that none of us type on a Dvorak today is one of the keyboard universe’s biggest injustices.

Some of those arguments are true, some not. Funnily enough, many of them are neither. Let’s unpeel the QWERTY and Dvorak myths and understand why the story is much more complicated than it appears, and much more interesting than most people give it credit for.

The first challenge: neither Sholes nor any of his inner-circle compatriots wrote a book, a paper, or even left behind notes explaining why QWERTY looks the way it does. This wasn’t an academic project, or a side interest. They were running a business. Sharing wasn’t necessary and could be corporate suicide. Either way, sharing would also distract from the hard, multi-year task of designing a typewriter.

Today, we can only piece the story from a scant few letters, patent applications, and models – plus a lot of informed speculation to fill in the blanks.

3

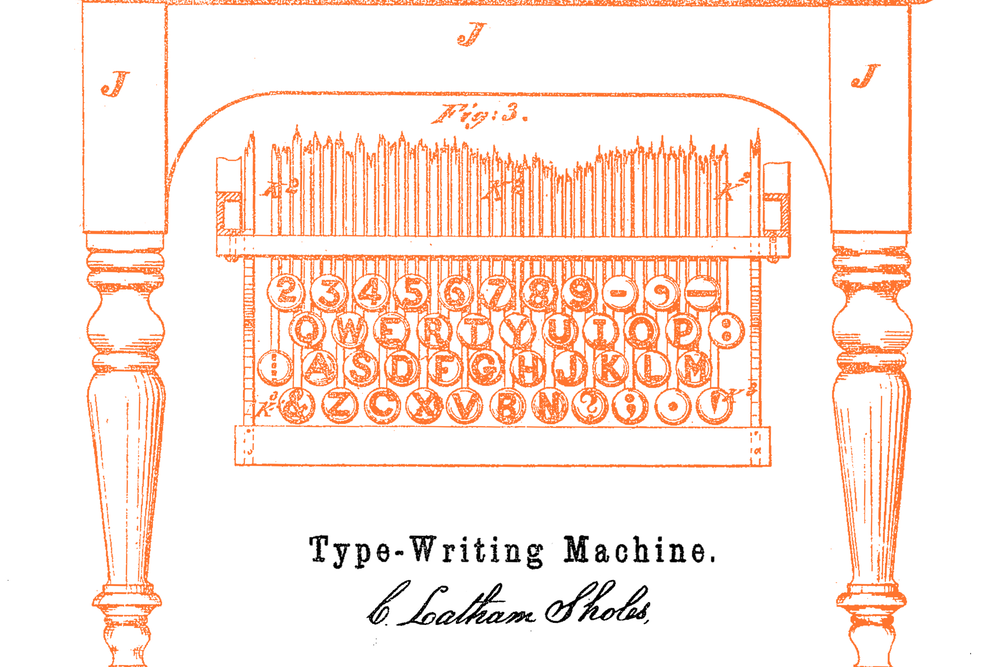

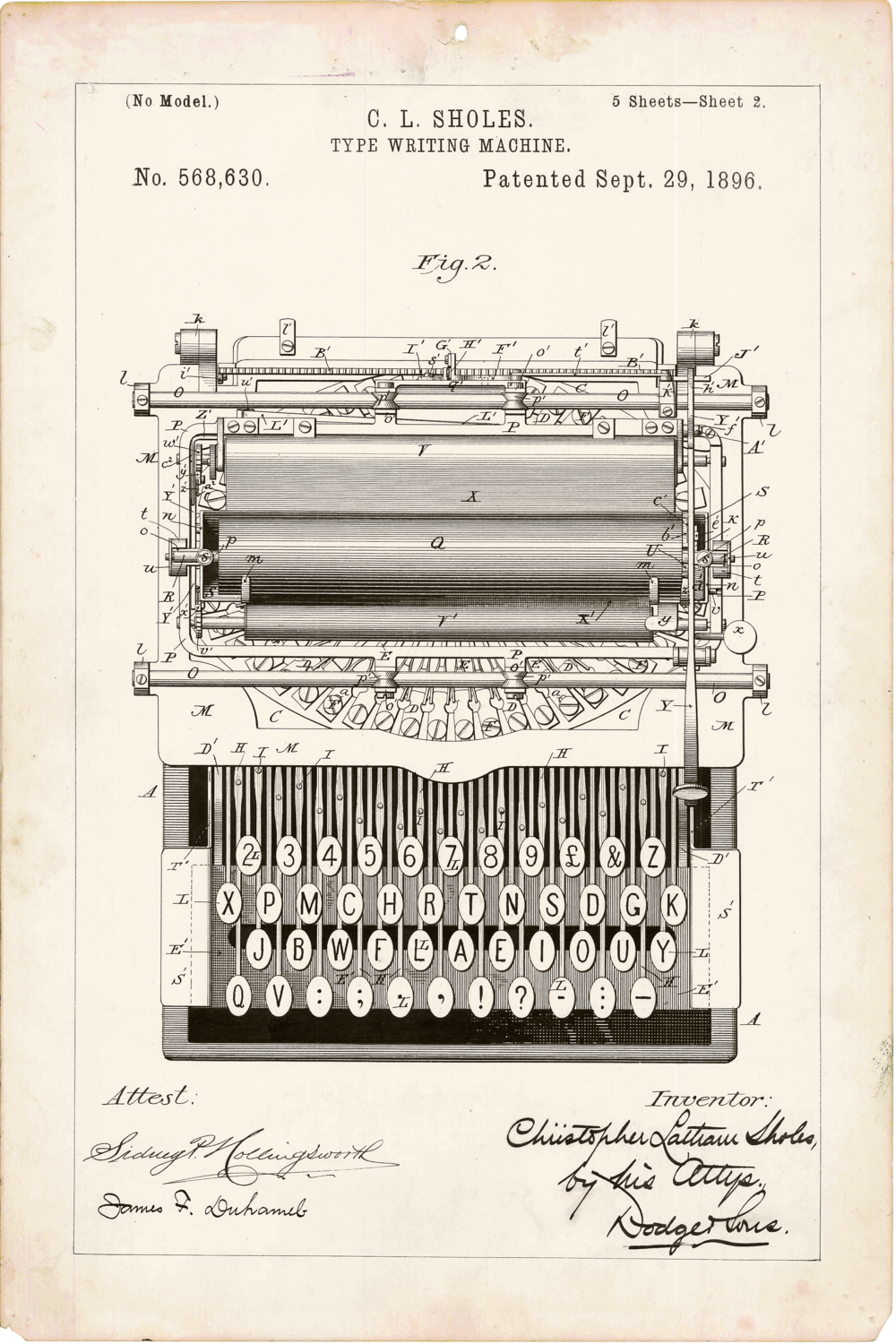

Some facts are certain. Early typewriter prototypes, the ones still looking like a piano, started in the most obvious, alphabetical order (or, at rare times, reversed alphabetical). Sholes had problems with some typebars bumping into one another while typing, and he started rearranging the letters to alleviate the issues. Remington made the last few changes after Sholes and Densmore gave them the rights to produce the machine.

There’s also the evidence of a tiny 1878 prototype typewriter used to test different typebar suspension ideas. That typewriter only has two rows of six keys each. The top one goes S O H L W I, and the bottom one R D T P E Y. These don’t seem like particularly exciting keys, except if you realize they can write a pertinent phrase: “SHOLES TYPEWRITER.”

But this was a tiny throwaway machine. As for the real typewriter, we’ve discovered enough models, patents, and illustrations to tell us the last four years of QWERTY evolution looked something like these layouts:

Historians don’t know if changes proceeded in that exact order – or whether some of them were transcription mistakes. But there’s enough smoke to know for sure there must have been fire: QWERTY did evolve between 1872 and 1876, and it’s likely its emergence started years before. Even if we don’t quite understand it yet, it no longer feels that the layout was just an act of randomness – we can see a definite process with small, deliberate adjustments to QWERTY being made over time.

The typewriter was advertised as three times as fast as writing with a pen. Sholes and Densmore successfully marketed the machine to telegraphers, who needed to transcribe the incoming Morse code at speeds of at least 50, if not 60wpm. Proof exists that Frank McGurrin could write at almost 100wpm at the Cincinnati speed contest – and that was only the very beginning of those competitions. Either Sholes was really bad at making QWERTY slow people down, or maybe that was never the goal.

We also know that QWERTY came before the Shift keys, and before touch typing itself. That timeline frees Sholes from some of the responsibility – how could he have been thinking of something that didn’t yet exist? And while it’s inconclusive whether QWERTY ended up as the best layout for touch typing, the very arrival of that method of typing – independently invented by many people – can be seen as a validation of QWERTY. It’s not hard to imagine a typewriter designed or built so awfully that touch typing never becomes an idea; or, if it does, it comes with no benefits. Indeed, most index typewriters would belong in that very category: they cannot be operated quickly or without looking.

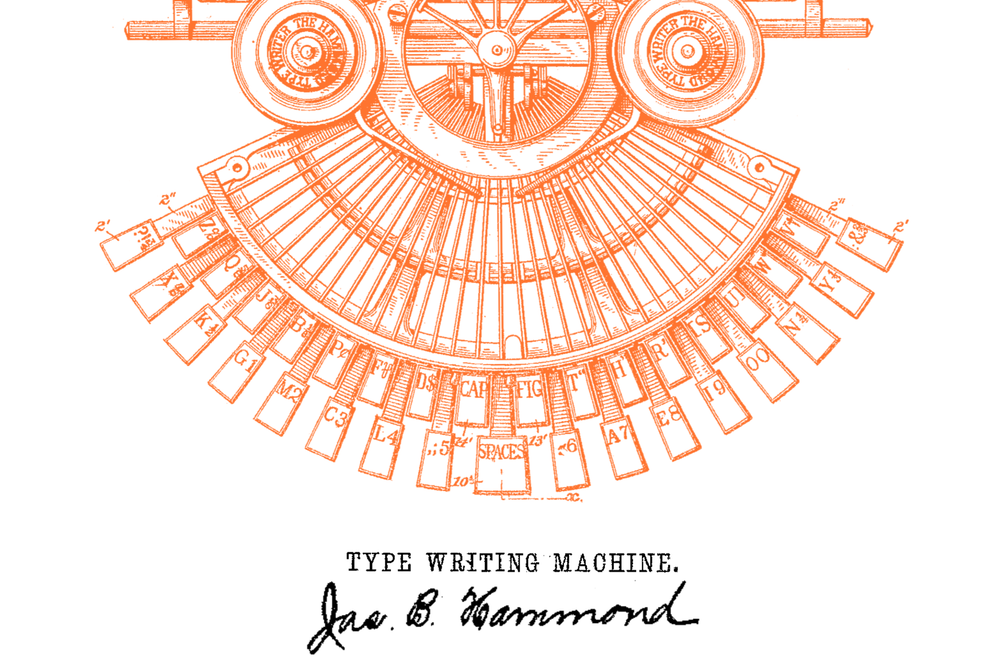

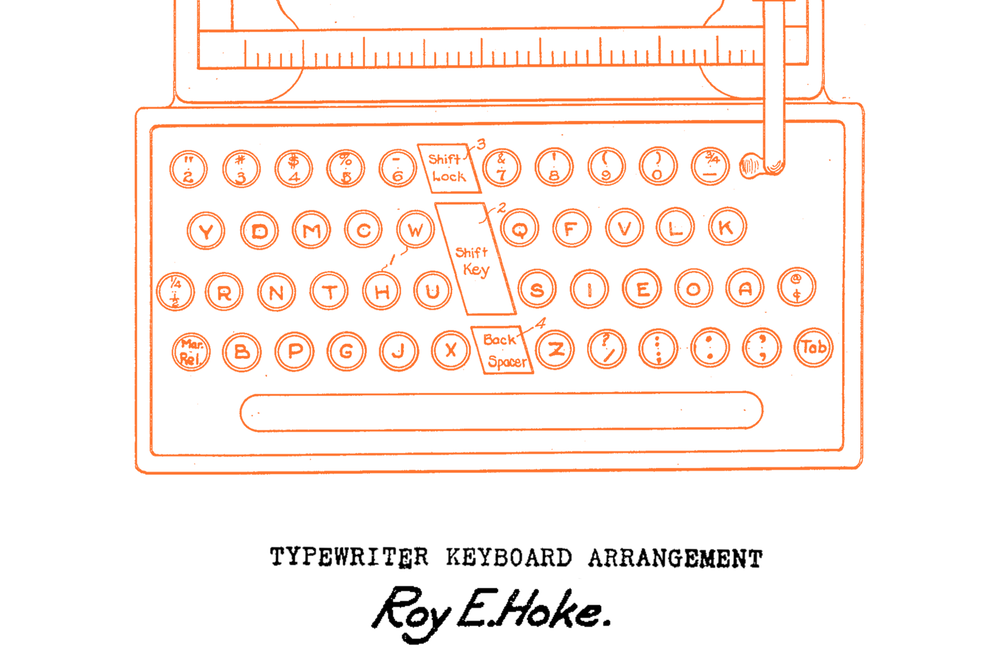

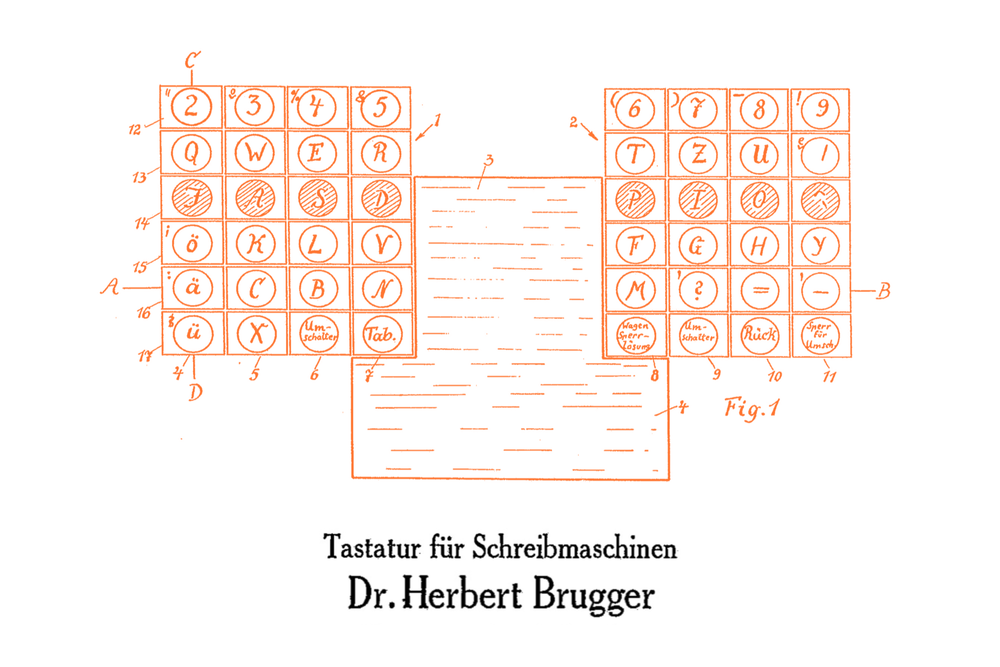

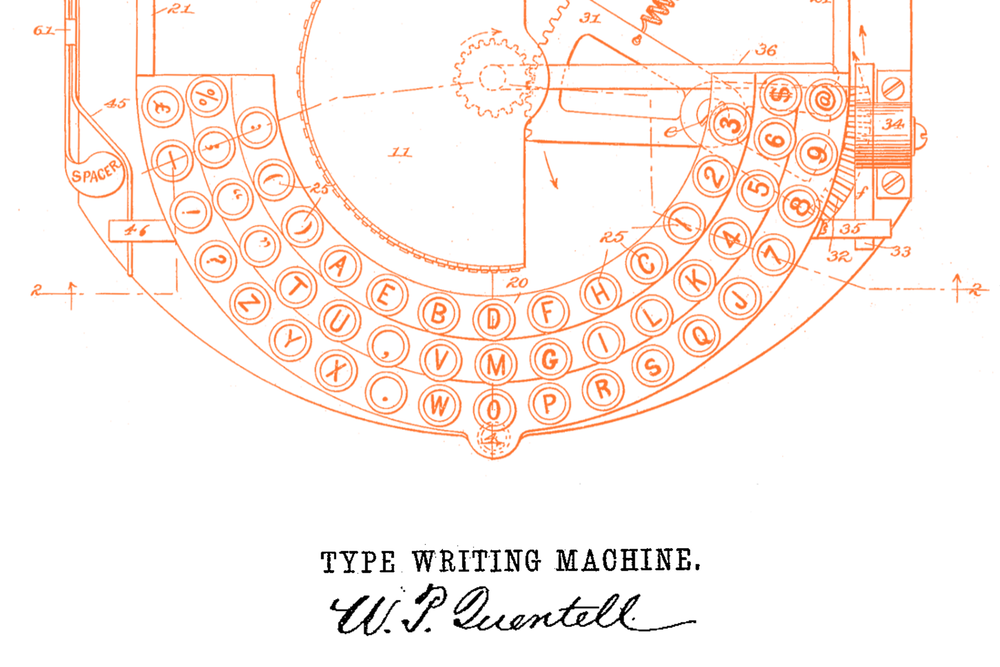

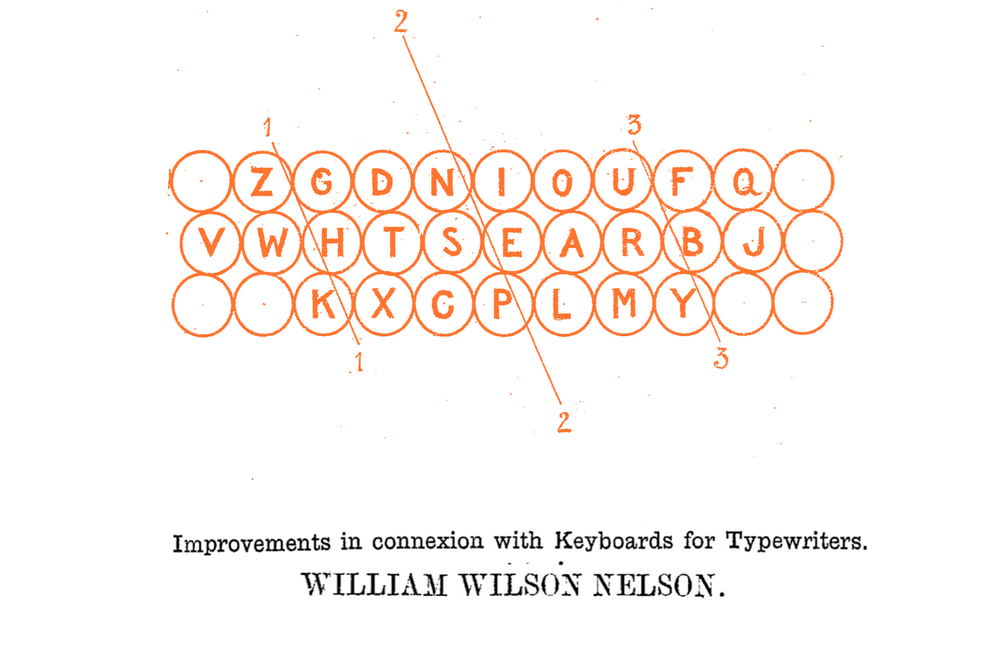

But when QWERTY was young, the possibilities were endless, and the future wasn’t yet set in stone. No wonder people tried to come up with a better key arrangement. It wasn’t only Blickensderfer. There was the Caligraph, the other Cincinnati typewriter; in the process of losing the Shift Wars, it shed its unique, non-QWERTY full-keyboard layout. There were the late-19th century typewriters named for John Hammond, Lucien Crandall, and Eugene L. Fitch, all trying something different, something smarter, than QWERTY.

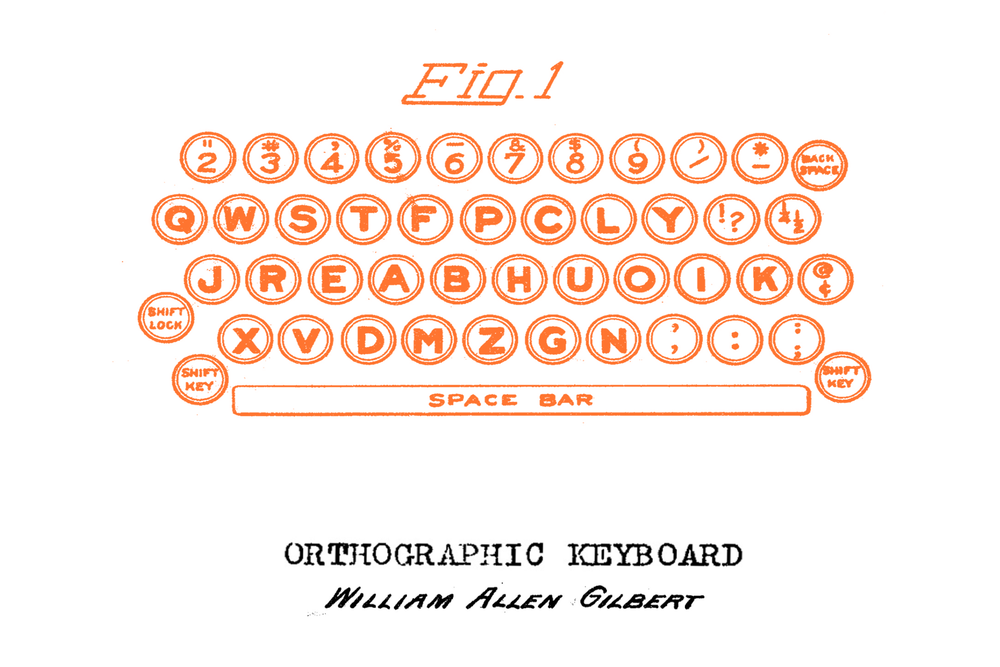

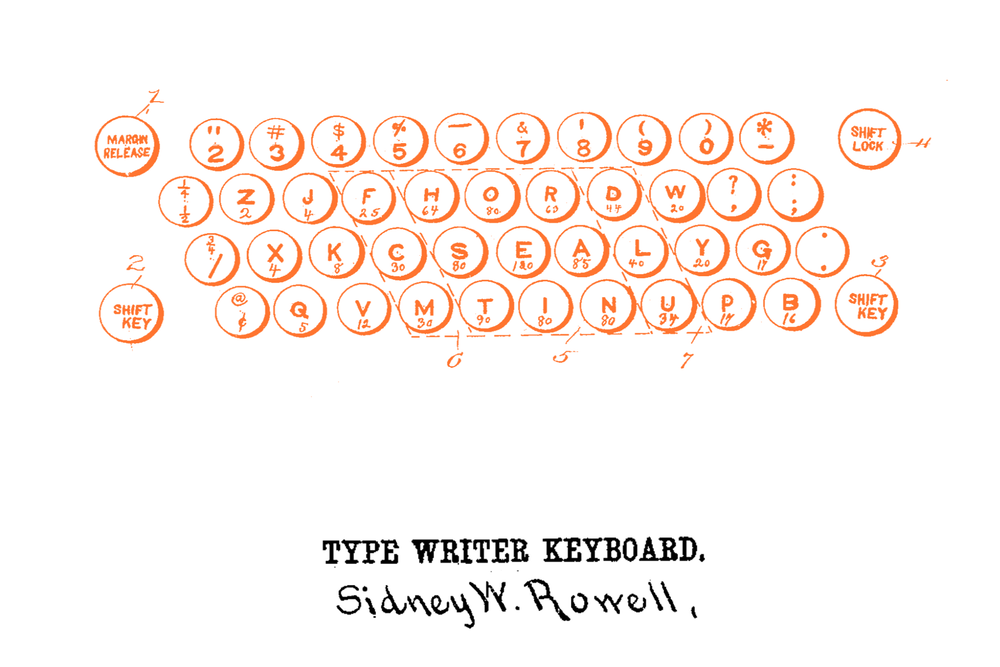

Then there were people whose interest in a better keyboard layout never went beyond a patent. William Robertson in 1888 hated K so much he moved it up to the digit row. In 1920, two independent inventors rearranged the keyboard so that the rarest keys like Q and X fell under the strongest, index fingers. In 1928, William Gilbert designed a hybrid model: most common letters under the index fingers, but rarest in the center.

We might scoff at some of their design decisions, but QWERTY didn’t seem to have design decisions to scoff at. And there was more. All of the inventors took into consideration either the combination of the frequency of letters or the way the typist’s hands operated. Increasingly, they did both. In most layouts, the few most common English letters – E,T, A – were flocked together. Blickensderfer’s Scientific keyboard had them in its DHIATENSOR row; Hammond’s Ideal keyboard put them right in the middle, weighted towards the stronger hand; Gilbert’s Orthographic keyboard arranged them in clusters around both of the index fingers.

All of them were keyboards with strong opinions – and none perhaps stronger than a keyboard layout called Simplified, designed in the 1930s by a professor named August Dvorak.

4

There weren’t many who hated QWERTY more. He found the original keyboard “crude,” “complacent,” a “patchwork keyboard,” a “disturbing irritant.” He called it “a haphazard imposition, wretchedly unbalanced, and absurdly awkward.” When he had to say “Standard keyboard” or “Universal keyboard,” he either put the word in quotes, or preceded it with “so-called.”

August Dvorak was born in Minnesota in 1894, part of the same family as Czech composer Antonín Dvořák. Dvorak was an educational psychologist and a professor of education at the University of Washington, and his life-long pursuit for improving keyboards has always been linked to teaching.

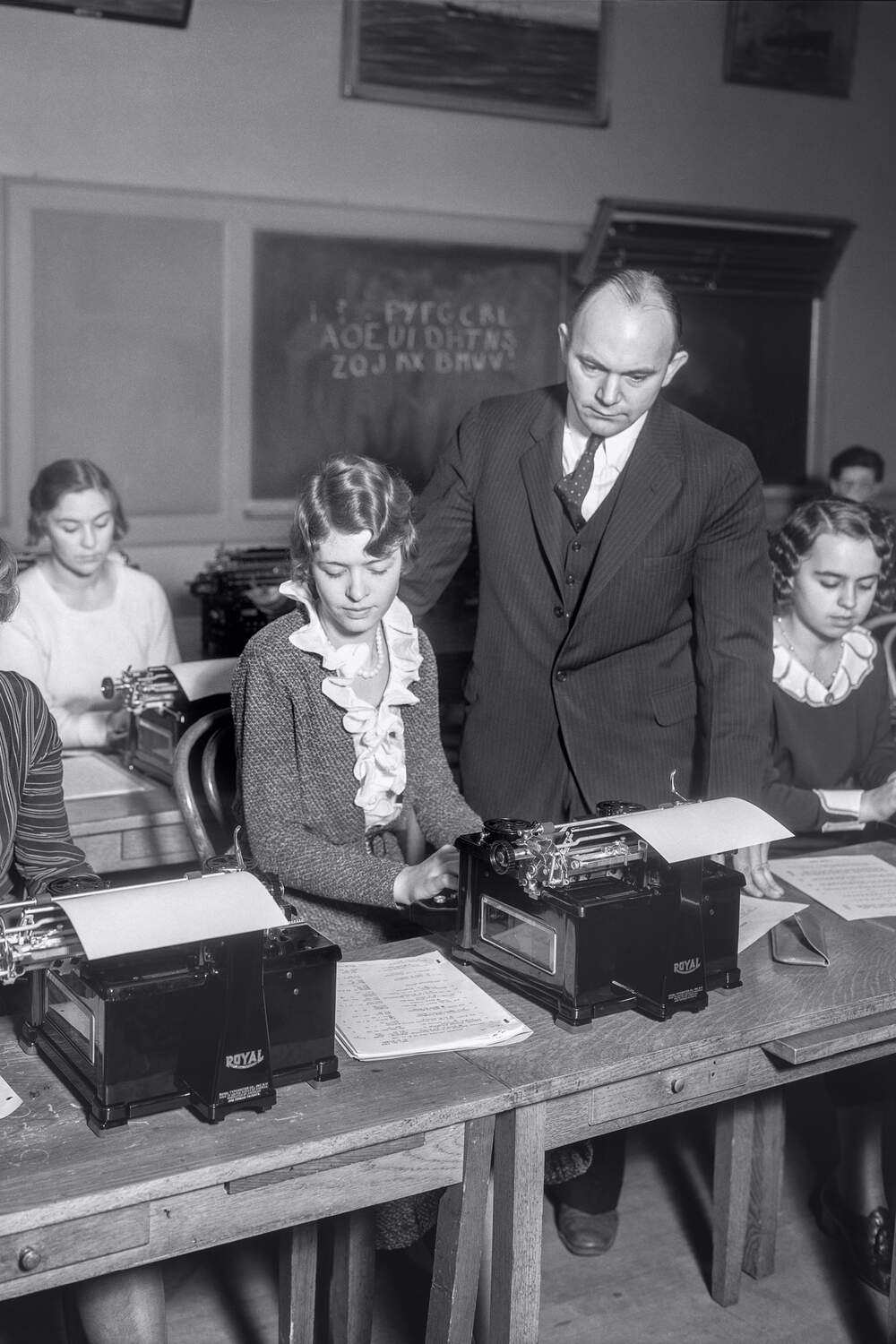

The passion was born when one of the students of the university, Gertrude Ford, started writing a Master’s Thesis on typing errors. She chose Dvorak to be her advisor, and he caught her bug, soon deciding a revision of the entire QWERTY system was the least he could do. He also enlisted help from William Dealey, his brother-in-law.

Designing the new keyboard took over a decade. Dvorak and Dealey applied for a patent in 1932, and wrote about the keyboard as soon as 1933, in paper with a beautiful name: Why And Wherefore Of Typewriting Errors. But the most well-known introduction to what they named “the Simplified Keyboard” was a 1936 book called Typewriting Behavior.

The 500-page volume is a tour de force of typing. It covers both the abstract and practical aspects of using a typewriter. It ventures into ergonomics and the psychology of typing – at one point it divides people who struggle with learning how to type into “tired typists,” “backward typists,” “slow typists,” and typists with “emotional upset.” It criticizes the teaching of typewriting (“Where in America today is there a comedy of errors to match contemporary typewriting instruction?”), and it does all that and more in a unique, riveting style. The book starts with this introduction:

It is a book in which factual data leave little room for personal impressions – a real distinction, as most students of the literature in this field will admit.

But it doesn’t stray from inspirational cries such as “show your hands honor for the strange power they bring you,” comparisons of the new keyboard to a jeep and the old one to an ox, and passages like this:

Daydreaming. All daydreams are pleasant. Whatever you wish, you win. On occasions when typewriting becomes unpleasant, isn’t it surprising that more students do not find a pleasant answer in daydreams? Even though you fail at typewriting, in daydreams you see yourself the salaried expert whose fingers dance lightly over the keys.

In Typewriting Behavior, you will find long tables of finger loads and word frequencies – but also gestalt psychology, hypnosis, Pavlov, “Doctor Freud of Vienna,” and chapters titled “The typist’s social heritage” and “The essential compromise between talking and doing.”

You will also find a thorough admonition of QWERTY, a page-by-page rebuttal of its layout. This is where Dvorak and Dealey went much farther than other keyboard re-inventors. They focused not just on the layout of the keys, but also on finger movements between them. Both of them admired Lillian and Frank Gilbreth, the pioneers of ergonomics who in landmark studies put little lights on people’s fingers and took long-exposure photos and shot movies to analyze their typing in practice, not just in theory.

So what exactly was wrong with QWERTY? Dvorak and Dealey said it overloaded the left hand, with 57% of typing happening on what for most people is the “non-preferred hand.” QWERTY didn’t spread the work between hands properly which would allow for more efficient typing – words like “federated,” “sweaterdresses,” “aftertaste,” “minimum,” and “pumpkin” all required unpleasant effort of one hand and one hand alone, and they were far from the only examples.

QWERTY also asked weak fingers to do much more work than necessary. There was a lot of “row-hopping” – fingers moving up and down needlessly – as well as “hurdles,” awkward movements where the same finger needed to move up and down to type subsequent letters. And QWERTY required the fingers to leave the confines of the home row far too easily. The key J in particular, the one under the typist’s resting right index finger, and the very same key that is adorned with a little ridge on a modern keyboard, felt like a particular slap in the face. In George Orwell’s Politics And The English Language, the letter “j” appears only a scant twenty-nine times – while “t” is used 78 times more often.

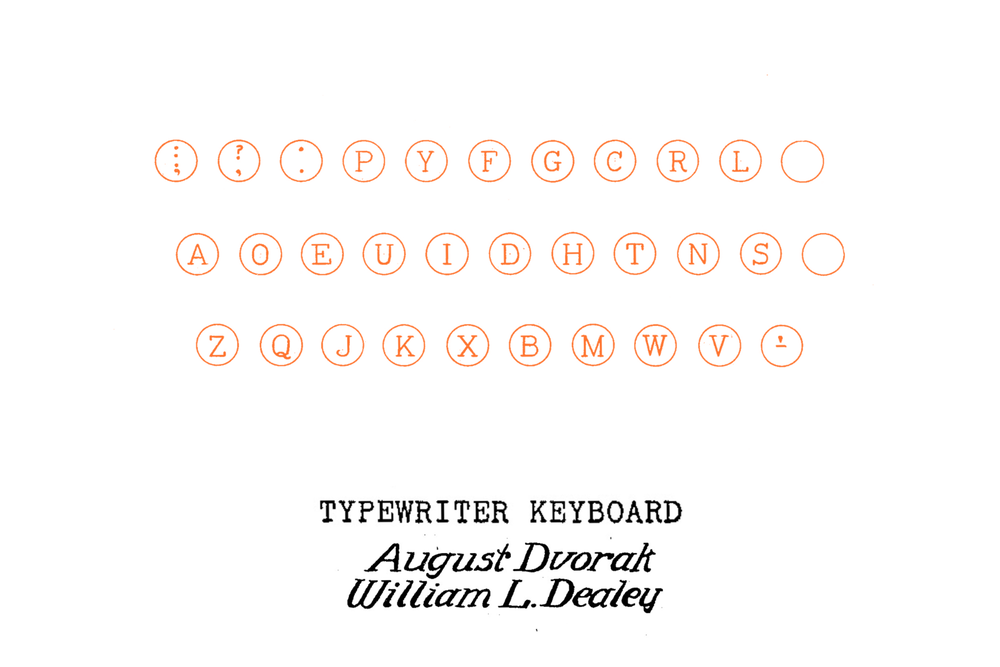

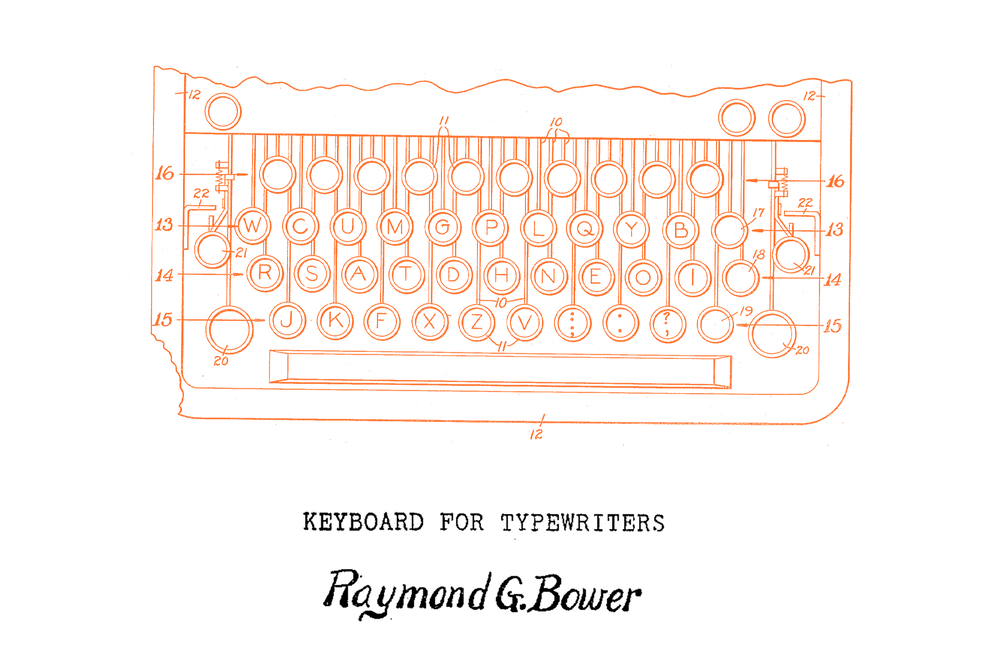

QWERTY was deemed a disaster. “Analysis of the present keyboard is so destructive that an improved arrangement is a modern imperative,” wrote Dvorak. That improved arrangement, the Dvorak-Dealey Simplified Keyboard, arrived on page 145:

Dvorak and Dealey didn’t want to relitigate the Shift Wars, so they wisely kept to an already standard arrangement of four banks of keys. But otherwise the biggest repudiation of QWERTY was in how little Dvorak’s keyboard had in common with it. The home row ditched the awkward, rare semicolon and gave the fingers ten letters; punctuation was moved from the lower right to the upper left; even the digits were rearranged for efficiency. The unused J was replaced in its prime position by H, used in Orwell’s book – and English as a whole – over forty times more often. Out of the whole keyboard only two keys, A and M, remained in the same location.

The new keyboard’s home row might’ve looked similar. It was the DHIATENSOR letters all over again. (Indeed, the Dvorak keyboard promised one third of English typing – or over 3,000 words – could be had without leaving the home row.) But a lot of what the keyboard accomplished was invisible until you started using it: the right hand now doing slightly more work than left, stronger fingers tasked more than weaker ones, the “hurdles” reduced by more than 90%. There was better balance, with only a handful of rare words typed by fingers of the same hand, rather than the thousands in QWERTY. Even the direction of the finger movement was considered. If you try to tap your fingers on the desk, they will naturally go one way and not the other; Dvorak’s keyboard layout incorporated that knowledge.

The Simplified Keyboard promised fewer awkward movements, more even rhythm, better hand allocation, and much less finger reaching. Instead of traveling 12 to 20 miles each work day, your fingers would now only need to cover one mile. The authors even listed “the typewriting demons,” the most misspelled words on either of the keyboards. For the new, simplified keyboard, the list started with “new,” “beautiful,” “during,” “everything,” and “help” – which meant very little until you saw that the same list for QWERTY is topped with “the,” “to,” “of,” “and,” and “is.” “It is expected that a simplified keyboard will be the solution to many of the problems which otherwise confront you, your instructor, and the manufacturer of your typewriter,” concluded Dvorak and Dealey.

If Sholes took QWERTY secrets to the grave, and many later keyboard patents left but a smattering of information about their design decisions, Typewriting Behavior almost over-explained all the theoretical principles.

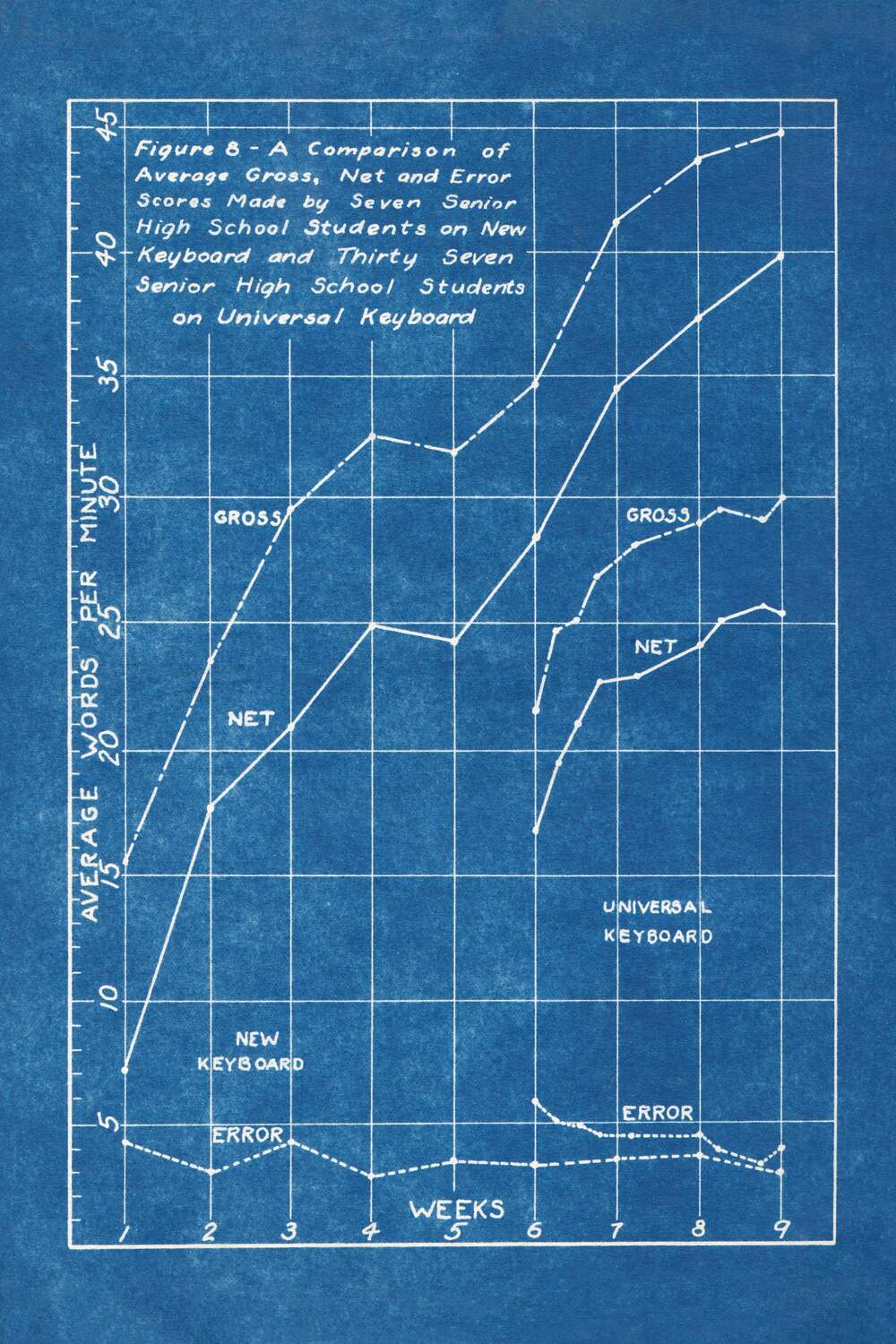

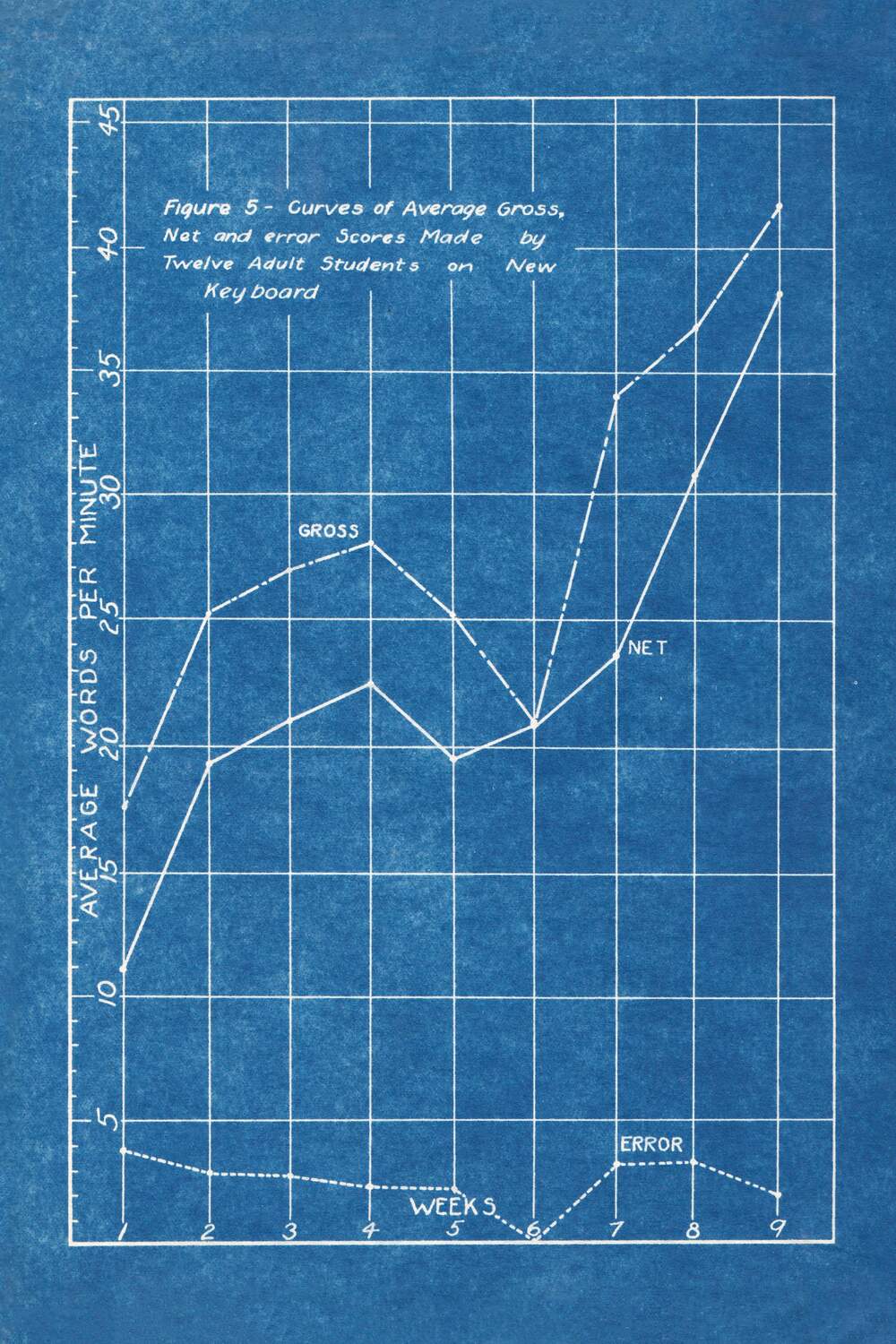

But the effort wasn’t just confined to theory. Dvorak and Dealey actually retrofitted a bunch of typewriters, taught students the new keyboard, and asked them to enter speed typing contests. They claimed that the output and efficiency in trials increased by 25% to 35%, and that the students dominated speed contests so thoroughly that they were asked to never come again.

Things were looking up for the keyboard now colloquially known as DSK. And Dvorak got better at promoting it. In 1943, he wrote an article with a much bolder title – There Is A Better Typewriter Keyboard – and much more evocative visuals showing grotesquely imbalanced hands of QWERTY typists, and their awkward movements. There were more positive studies, too: a 1941 American Management Association trials concluded with, “All six retrainees were enthusiastic about the Dvorak keyboard and did not want to return to the QWERTY keyboard.”

And in 1944, the keyboard received its biggest break yet. Resource-strapped because of World War II, the American Navy wanted to test switching to Dvorak’s keyboard, which promised more productivity. Fourteen typists were retrained from QWERTY to DSK, and the results were sensational. Just fifty hours into retraining, the typists could recapture their original speeds. Eventually, they all ended up typing, on average, 75% faster – with one person increasing their rate to almost 2½ times faster than using QWERTY. Their accuracy improved by an impressive 68% as well. All in all, the new typewriters started paying for themselves a mere ten days into retraining.

Here it was, in black and white: proof that the new keyboard was easy to learn, more accurate, less fatiguing, more efficient, and overall “easier and more enjoyable.” The typists were “unanimous in their approval.” One newspaper reported one of the typists routinely reaching 180wpm at a time when the world record on QWERTY was 152wpm.

“Indisputably,” the report concluded, “it is obvious that The Simplified Keyboard is easier to master than The Standard Keyboard.” The Navy immediately opened a bid for 2,000 Dvorak typewriters. The future of the Dvorak keyboard never looked brighter.

5

But the Navy never switched to Dvorak. For reasons that never became clear, the bid was cancelled by the U.S. Treasury Department, and the whole study classified. Then came another blow – a disastrous 1956 experiment by the General Services Administration. “U.S. plans to test new typewriter,” blared The New York Times headline, adding “A revised keyboard is said to increase output by as much as 35%”.

It was a four-month experiment, led by Dr. Earl Strong. It involved twelve typists picked from ten federal agencies. “The inventor of the simplified keyboard insists it can tremendously increase office efficiency and save millions of dollars all over the place. If the test bears out his claim, the Government may gradually adopt the simplified keyboard and industry might follow suit.” It was, in other words, “one of the touchiest experiments of our time,” and a future article sensationalized the issue even further, saying “revolution is in the air.”

But four months later, the headlines started telling a different story. “U.S. balks at teaching old typists new keys,” reported The New York Times, adding “The GSA reported today it has at least temporarily abandoned the idea of equipping the Government with new Simplified typewriters.” It turned out that after training, the control group of QWERTY typists actually performed better than Dvorak ones. Strong concluded that there were few advantages to switching to the DSK, and that his recommendation was just to ask typists to repeat their QWERTY training.

This was a major blow to the acceptance of DSK. In time, people who cared divided themselves neatly into the 1944’ers and 1956’ers. The first group pointed out that Strong was “hardly an unbiased investigator,” and that in the years before the study he spoke openly about his desire for doubling down on QWERTY. They also pointed out the data of the study told a different story than its conclusion – at least the summary data they had access to, since Strong inexplicably destroyed the raw data, except for one piece of film that he saved as a souvenir. Another observer called the GSA report “poorly designed,” said its conclusions were “overstated,” and the entire endeavor was “a lesson in how to defeat progress.”

But the 1956’ers had ammunition, too. Despite many other studies run since, why did no one manage to replicate the fantastic results from the 1944 Navy study? Could it be, perhaps, that the Navy’s top expert in the analysis of time and motion studies during World War II was none other than the Lieutenant Commander of US Naval Reserve named August Dvorak? “The experiments in the Navy study were biased and, at worst, fabricated,” declared one commenter, with others referring to it as “August’s cooked books” and calling Dvorak a “mercenary huckster.”

That the Navy study was “accidentally” classified as secret for a number of years was to 1944’ers a sign of a conspiracy, and perhaps a nod towards the QWERTY lobby, consisting of typewriter manufacturers and typing schools. To 1956’ers, it was just righting the earlier wrong, the classification covering up a conflict of interest, statistically insignificant results, badly interpreted math, and selective omission of results that shone a bad light on the DSK. “How can we take seriously a study which so blatantly seems to be stacking the deck in favor of Dvorak?”

The 1944’ers suggested the opponents exaggerated both the retraining and the typewriter conversion costs, and that the claims of DSK being faster scared away typewriter manufacturers – increased output meant fewer typists and fewer sales – and even typists themselves, worried about their jobs during The Great Depression.

The 1956’ers instead pointed out Dvorak’s business mistakes: the first DSK typewriter was a Noiseless, a machine with a very unusual feel, in and of itself a tricky beast to adopt – let alone when sporting a completely different layout. The name was weird, too. The keyboard was perhaps more comfortable, better thought out, faster – but with the identical number of keys, DSK did not exactly feel Simplified.

And then there were the rearranged digit keys, to the 1944’ers a proof of a methodical, scientific approach – and to 1956’ers a sign of arrogance and disconnect from reality. And, speaking of numbers, that Navy typist looking “nonchalant, and a little bored, today as she zipped along at 180 words a minute”? It turned out the impressive number was just, in the ultimate of ironies, a typo. Her output was not 180wpm, but a mere 108.

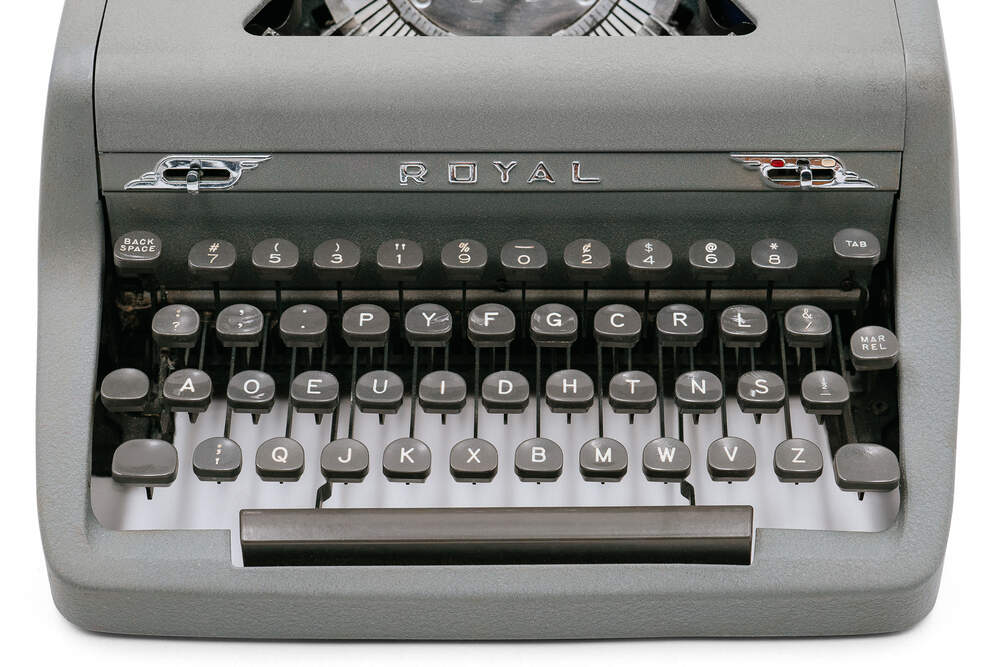

The DSK limped along. Some typewriter companies – Royal, Smith Corona – offered keyboards with the new arrangement as an option. Dvorak continued his work. He kept thinking of the typists, creating two versions of his keyboard for one-handed typists, and providing his usually sharp commentary: “To require the one-hand amputee or paralytic to master touch typing on the QWERTY keyboard is a form of sadistic cruelty reminiscent of the worst in the Middle Ages.”

In time, he grew frustrated with his work being ignored. Proposing a new layout was, in his words, akin to “reversing the Ten Commandments and the Golden Rule, discarding every moral principle, and ridiculing motherhood.” When interviewed in 1962, he snapped at the interviewer. “I’m tired of trying to do something worthwhile for the human race, they simply don’t want to change!”

He switched to other interests, mainly statistical psychology. And yet, during his death in 1975, at the age of 81, he was in the middle of writing Synergistic Typing For The Simplified Keyboard, the ultimate DSK book eagerly awaited by the 1944’ers.

Soon after his death, the arrival of personal computers showed some promise. Making a computer keyboard understand Dvorak was much easier than physically modifying a typewriter. Also, many new people who never typed before and never acquired a fondness for QWERTY were sitting down to their first keyboards. And, around the same time, Dvorak’s layout became codified as an American industrial standard. “It may be taps for the QWERTY keyboard,” blared a headline in the Washington Post. “Thanks to the computer chip, a speedier keyboard’s time seems to have come.” The president of a new organization called Dvorak International Federation said she saw a fifty-fold increase in the number of Dvorak typists between 1974 and 1984, and summarized it as “the Dvorak is on its way.”

But the revolution didn’t come this time, either. Some people switched their computers to Dvorak and never looked back. Most remained with QWERTY. Incidental studies of the DSK continued; they came and went without the drama of the 1944 Navy Study and the 1956 GSA Study – but they established little that was new or exciting. A few more reputable ones showed a speed increase for Dvorak, but at single-digit percentages it didn’t seem worth much attention. A few less reputable ones showed better results, but even those never reached the heights attained by the studies ran with August Dvorak’s involvement.

6

At the same time the second wave of interest in Dvorak faded away, there was a new excitement in… QWERTY.

In 1985, an academic economist Paul David wrote an essay that ended up becoming one of the most cited economic papers of all time. It was called Clio And The Economics Of QWERTY – Clio being the muse of history – and started in a lyrical way that would make August Dvorak happy: “Cicero demands of historians, first, that we tell true stories.”

David argued that the continued omnipresence of QWERTY is a perfect example of path dependence – decisions driven by a prior historical path rather than an objective look at what’s out there – leading to lock-in. We standardized on the wrong system too early; DHIATENSOR should’ve won over QWERTY, and Dvorak should’ve conquered DHIATENSOR.

Other people built on that line of reasoning. The same thing happened when VHS won over Betamax in the 1980s, and when Windows took over Mac’s market share in the 1990s. Two researchers went as far as to suggest the idea of a “QWERTY problem,” defined as “an inferior industry standard that has prevailed possibly because of historical accident.” The stakes suddenly became very high. “In the world of QWERTY one cannot trust markets to get it right,” wrote Nobel laureate Paul Krugman in 1994. QWERTY, staring all of us in the face every day, was a reminder that you couldn’t rely on the world to pick the better thing, or to right its wrong even when it realized it.

The argument was predicated on what seemed like the obvious assumption: that Dvorak is good, and that QWERTY is bad. But the new group of 1944’ers found their 1956’ers, too. In 1990, Stan Liebowitz and Stephen Margolis published a counter-essay called The Fable Of The Keys. They argued that it was as impossible to say QWERTY was bad as it was that Dvorak was better. They pointed out new flaws in the 1944 study and the absence of more modern evidence for Dvorak’s superiority. They ridiculed Typewriting Behavior as “a late-night television infomercial rather than scientific work.” They recalled the touch typing contests of Frank McGurrin and the parallel victories of people typing on other layouts. The victory of QWERTY was not preordained, they claimed. QWERTY didn’t randomly conquer the competition because there was no effective competition; QWERTY won despite it. “The victory of the tortoise is a different story without the hare,” they summarized.

As for the other battles cited by the 1944’ers? They argued the public recollection of Betamax being better than VHS was severely tainted. And as for Windows and Macs, the best counterpoint to that argument was a simple passage of time: after the utter dominance of Microsoft in the 1990s and 2000s, the market tides turned towards Apple in the new millennium.

The discussions were soon joined by famous names such as Krugman, Jared Diamond, and Stephen Jay Gould. They also became heated and surprisingly personal. Liebowitz and Margolis’s paper was called “the eight rambling pages.” “What do they have to gain by bashing Dr. August Dvorak’s gift to humanity?” asked another observer. On the other side, we saw comments such as “How someone who had the intellectual ability to earn a doctorate can misread the logic of his colleague’s claim so completely is astonishing.” Liebowitz and Margolis themselves called their 2010 paper How The Lock-in Movement Went Off The Tracks before renaming it to a slightly gentler The Troubled Path Of The Lock-in Movement.

Both sides were angry. The 1944’ers lamented the survival of the fittest being replaced by survival of the luckiest. In a perfect world, we’d all type on Dvorak, they said. The 1956’ers disagreed. In a perfect world, we’d realize Dvorak keyboard wasn’t perfect. For a while, there was so much activity you’d be excused for thinking QWERTY was some fresh invention, rather than something hacked together over a century earlier.

7

But was it hacked together? The most interesting QWERTY paper of the modern era asked that very question. It was written by researcher Neil M. Kay in late 2011. Kay decided to ignore market adoption rates, stories of touch typing contests, and instead looked where, surprisingly, few people did. Perhaps Sholes left behind little documentation, but maybe there were clues in the keyboard itself – and in the machine it was connected to.

One of the persistent myths about QWERTY was that it was designed to slow people down, and it did so by moving frequent letter pairs far away from each other. The logic was: the further away the common pairs of letters, the slower your typing, and fewer chances of the letters clashing as you type, bringing the whole process to a halt.

Kay decided to question each part of that logic, starting with the last one. If you ever typed on a typewriter, you’re probably familiar with the idea of two typebars colliding if you press them at the same time, getting stuck close to paper, and requiring them to be untangled by hand.

This, however, only happens to really inexperienced typists and, besides, the typewriter that QWERTY was designed for looked very different than later typewriters. There, the typebars were arranged in a semicircle. As a typist pressed the keys, the typebars moved away towards the paper. The arrangement, popularized by the Underwood №5, is called “front-strike,” and the typebars were supplied with counterweights so that they return to their rest position as snappily as they move away to strike paper.

But Sholes and Densmore’s original typewriter was arranged differently. The typebars were bigger and arranged in a whole circle underneath the paper on the platen. A typist’s key press swung the typebar upward, and it fell back assisted by gravity alone. As you’d expect, this earlier mechanism – retroactively named “up-strike” – was much less refined. It wasn’t only prone to clashes when someone pressed two keys at the same time. It was also in danger of them if a typist pressed two letters in close succession that resided on two adjacent typebars: as the previous typebar was falling down, it could be caught by the one going upwards, causing the wrong letter to be repeated. Because this happened out of sight of the typist, they might have not realized the damage until after they typed an entire page, when they raised the platen and retrieved the paper.

Kay analyzed how the keyboard would’ve looked in 1874, but also how it would have behaved. The layout appeared almost the same on the first Sholes & Glidden as it did on the first Underwood, but what happened behind it was much different.

Kay followed that observation with some good old-fashioned statistical analysis. Instead of speculating, he took Life On The Mississippi – the very first typewritten manuscript – and ran it through a computer simulation.

The results? On a purely alphabetical keyboard, which is known to be Sholes’s starting point and traces of which are still visible in the home-row sequence D F G H J K L, the fast typist would see their typebars clash on average once every 26 words.

On a QWERTY keyboard, it was once every one thousand words.

QWERTY wasn’t a mistake. It wasn’t random. The numbers proved it was deliberately designed to avoid the most common technical problem of its time – and to do so with an astonishing efficiency. Twain’s typist could write an entire 145,000-word manuscript, and only be in danger of typebars clashing 146 times.

Kay’s math explains why the E and I were moved up from the alphabetical order of the middle row (they were much less prone to clashes this way), the late changes from Z C X to Z X C, and the aesthetic move of M from the middle row to the bottom one. It explains why Remington swapped the layout to AZERTY for France, QZERTY for Italy, and QWERTZ for German: they all received the minimal amount of changes to fix the clashing typebars for their respective languages. Kay’s math even disproves one other story repeated for a century: Sholes did not move frequent pairs away from each other on the typebars – he moved infrequent ones closer.

The 2011 paper helped clear QWERTY’s reputation. It drew accolades and responses from the most prominent 1944’ers and 1956’ers. DSK might have been designed with much deliberation over the course of a decade – but it looked liked so was QWERTY. It was carefully specced out and evolved over many years to solve very specific technical problems without sacrificing much more. It wasn’t built to slow the typist down, it wasn’t the worst layout possible – not by a stretch – and it ended up okay for touch typists despite being made before the technique was invented.

Did Sholes put T-Y-P-E-W-R-I-T-E-R letters in one row on purpose? We might never know, although Kay analyzed that too. He calculated the chances of this happening as only one in 5,000, suggesting intentionality, and even rationalizing why it had to happen in the top row.

And speaking of marketing gimmicks: was QWERTY’s success helped by the incredible marketing muscle of Remington? Yes. And we’ll never know by how much.

On the DSK side there was only anecdotal evidence that their layout was faster – the more solid the study, it seemed, the smaller the advantage. Was the layout kinder on your fingers? Yes. The math about fingers traveling less checks out. Watch someone type on Dvorak, and their hands seem stationary; many Dvorak studies end with people praising the new keyboard as being lighter on their fingers.

But Dvorak being more comfortable doesn’t automatically make QWERTY uncomfortable, and that leads us to the main question: Is Dvorak better than QWERTY?

8

It is, turns out, a question impossible to answer. The challenge is that QWERTY and Dvorak were separated by sixty years; each one was really good at what it was trying to do, and each one’s approach was slowly undone by technological progress. QWERTY tried to solve the problem of clashing typebars and we know today it did so with aplomb. Dvorak’s main complaints were about unnatural finger movements, hurdles, the imbalance – and his layout fixed all of these problems. If we judge one by the other’s standards, neither can win. Next to Dvorak’s rationale, QWERTY indeed feels hopelessly inefficient. But put a DSK in a 1874 typewriter and it will fail miserably, too, any advantage coming from its finger-friendliness lost as the typebars collide over and over again.

Today, some still swear by their Dvorak keyboards and their ergonomic benefits. Once in a while, a modern tech publication presents a long article about one of the writers trying to switch to Dvorak. In 1996, one of them started with, “It took me 103 seconds to write this sentence.” Casey Johnston, then a writer for the tech site Ars Technica, wrote a surprisingly gripping tale in 2014, involving moments like, “Typing numbers is now my favorite activity because everything is in the same place” and:

A couple of times I’ve let my computer fall asleep by accident with the Dvorak layout on and experienced very real panic that I would never be able to get my login password right.

Every comment section below any such article is a return to 1944’ers vs. 1956’ers: half the audience cheering their half on while razzing the rest. And the old QWERTY/Dvorak myths are still perpetuated. QWERTY is called “hopeless” and a “marvel of inefficiency.” “Have you ever stared at your typewriters keyboard and seen no more order to its letters than those found in a bowl of alphabet soup? Have you ever suspected that there was some conspiracy to make typing as difficult as possible?” mentions PC Magazine in the 1980s in one article, and another features an entire section about “QWERTY’s ignoble birth,” and then asks, “Why use QWERTY, a keyboard designed to be difficult, instead of Dvorak, a keyboard designed to be simple?”

But if Dvorak was once a modern equivalent to QWERTY, it’s now older than QWERTY was at Dvorak’s introduction. Just as there were patents for keyboards before Dvorak, there were many in the years since – and in the most recent decades, instead of patents, some of the ideas became software. Search the internet, and you can find a way to switch your keyboard to Colemak, or Workman, or PLUM (a layout that spells out P L U M and R E A D O N T H I S). All of them, just like Dvorak, are optimized for English – but you can also find a German-specific Neo, and French BÉPO which tries to atone for the sins of AZERTY.

Each one of these tries to do something new, and if none of them work, you can design your own and swap the keycaps within minutes – a task infinitely easier than it was for Sholes, Blickensderfer, or Dealey and Dvorak.

But unless your keyboard bothers you physically – in which case trying a new layout might improve your health – switching to a non-QWERTY layout or even designing one’s own feels positively academic. At times, it reminds me of people creating their own artificial languages, and their always futile attempts to rewire the world the way they want to look at it.

But there’s a difference. If you’re not bothered with other layouts existing right next to yours – a genuine worry every time you have to use another computer – your only challenge is in your ten fingers and your one keyboard speaking to each other. I can’t help but admire this idea to try to be better, to invest in one’s tools, to make an improvement even if purely aspirational, to squeeze just a bit more out of that odd pairing of human hardware and artificial hardware.

Why did Dvorak’s keyboard fail? I posit that it didn’t. It achieved exactly what its inventor intended: an alternative to QWERTY – and an inspiration to those who wanted or needed one. Turns out, not very many people did. Not during WWII, not in the 1980s, and particularly not today, when the percentage of typists who need to type very fast and error-free is lower than ever. Dvorak thought of people who spent 10 hours a day typing, but in the grand scheme of things those people are almost as rare today as they were in the young years of QWERTY. (“I’ve got a lot of problems, but none of them can be solved by typing a wee bit faster,” summarized a popular comment.)

Dvorak might indeed be faster and more comfortable. The thing is: it doesn’t matter. QWERTY is not too bad. For most people, it is good enough. “Good enough” might feel like a disappointing badge of honor, but the irony is that most who complain about “the tyranny of QWERTY” or “the curse of QWERTY” write so on a QWERTY keyboard. One can look at QWERTY and see it as the market standardizing on something awful – but you can also see QWERTY as, well, okay, except surrounded by exciting legends of its bad reputation, and inspiring yet idealized underdog layouts that provide only a small improvement.

“One could assume that as the typewriter progressed, so too should have the keyboard,” the typewriter collector Greg Fudacz wrote on his blog. They did, except you have to consider that there is so much more to keyboards than just the arrangement of keys. But before we move on to talk about all that, let’s come back once more to Sholes.

9

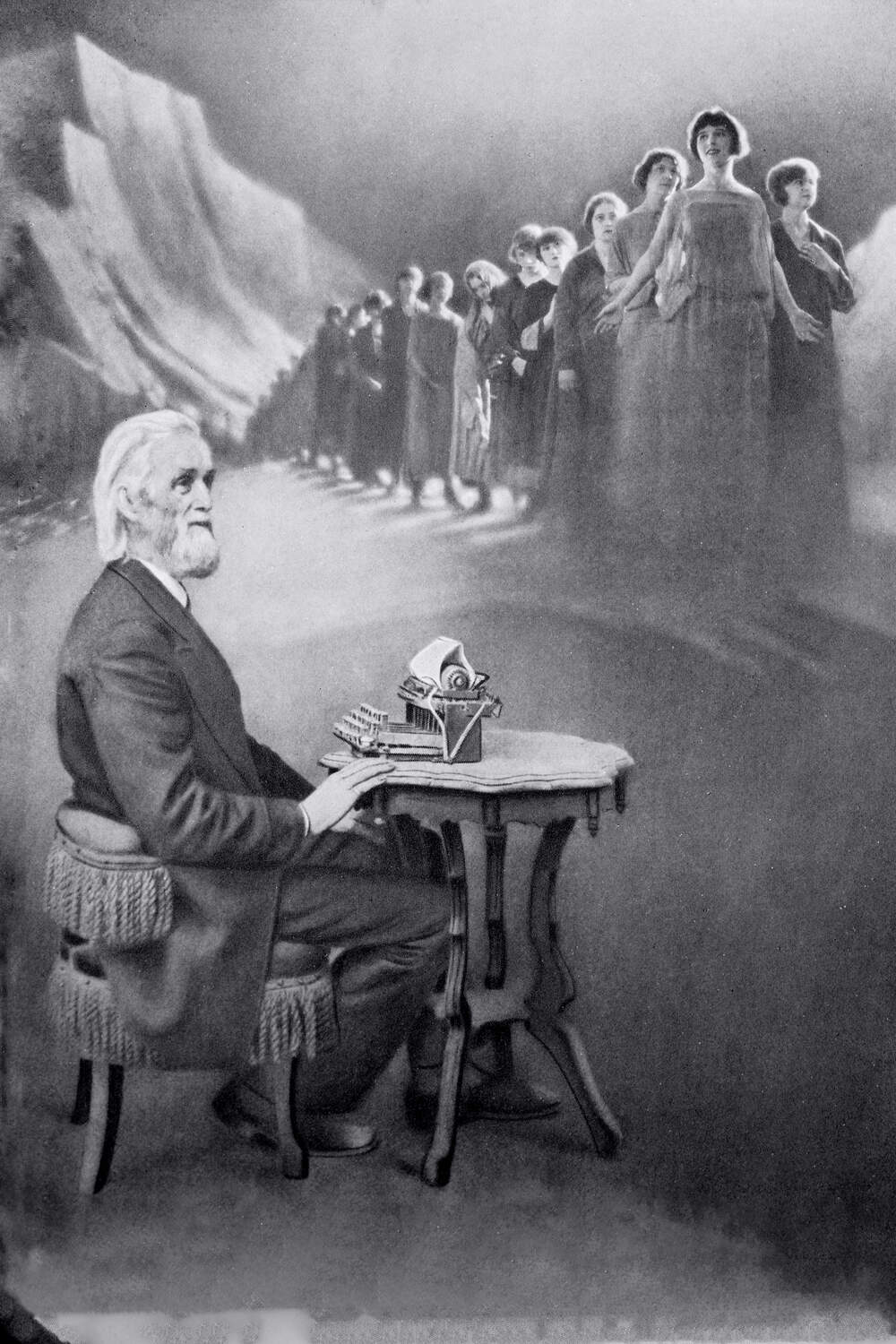

There weren’t many who hated QWERTY more. In his waning years, Sholes grew to despise Densmore – but also his own keyboard, and everything that Remington did with it.

This partly explains why Sholes left little behind. He wasn’t interested in documenting the typewriter project he grew to detest, and he considered his newer endeavors trade secrets. That included his never-released portable typewriter and his continued experiments with layouts that were meant to best QWERTY.

The only thing that remains from those experiments is one prototype and a matching 1889 patent. They both show a unique keyboard. It starts with X P M C H and R. Just like Dvorak decades later, it groups all the vowels under one hand (except this time the right one). It puts the punctuation exclusively in the top and bottom rows.

In the patent, the keyboard is there just as an illustration. Sholes doesn’t give it a name, or explain it further. But Kay and others analyzed it, too. If QWERTY was really good at avoiding the kinds of typebar collisions that plagued the early typewriters, this keyboard was nearly perfect.

Two years after Kay, in 2015, a researcher named Thomas A. Fine ran his own set of similar simulations, and agreed:

I have tried to simulate the odds of randomly finding a better keyboard than this one (at avoiding adjacent type-bar collisions). The program ran for a week, and tried more than 40 trillion keyboards, and found no keyboards as good as this one. The odds of one person winning two Powerball lotteries back to back (after entering each lottery only once) are more than ten times better than this.

Sholes’s newer keyboard was an excellent one, even flawless in one regard. But it never graced a production typewriter.

C. Latham Sholes died just five months after filing the patent. His layout became yet another scheme that succumbed to the QWERTY monster he had unleashed fifteen years before. He would never see QWERTY win the Shift Wars, befriend touch typing, conquer data processing and teletypes, seduce computers, take over all of the international keyboards, and lodge itself successfully in our pockets. He also would never see his creation brush away Blickensderfer’s Scientific as easily as it did dozens of other keyboards.

August Dvorak was born just four years after Sholes died, making it impossible for them to meet. Yet I like to imagine them hanging out together, looking down from above, laughing at us as we try to figure out their creations so many decades after they left us. It seems like it wouldn’t be hard to know which sides they would pick, and which one of them would be a 1944’er and which one a 1956’er. But in this story filled with myths and mysteries, I am no longer sure.